SS: Your art practice has been evolving in front of my eyes, so to speak, yet I do not know anything about the beginning. What or who inspired your decision to become an artist?

SMcK: I hoped to be an artist from as early as I can remember and given that my other desire was to be a brain surgeon, art was the only realistic option. My father painted war art and when I was a child, he showed me how to paint and I spent my time watching him. Play disinterested me so I pursued my art. There was never much doubt that this is what I was going to do and my parents encouraged and supported me.

I was first drawn to artists like Eduard Munch, without much interest in romantic landscapes. The environment around me had a strange beauty as a quarrying isle. I think the dissection and destruction of the stone landscape influenced me. The first artist I consider of great influence on me was Frida Kahlo in whom I saw a penetrating questioning and acceptance of reality; of physical pain and psychological disharmony. Here was art which was not all pretty and agreeable but which actually meant something, probing the façade of people’s falseness to show what was really going on. That is what interests me; looking beneath the skin to underlying activity and behaviour, feelings. Later this developed into research in anatomy, psychology, and neurology.

A significant influence on my artistic direction came when I saw a Louise Bourgeois exhibition in Oxford whilst doing my A levels. In her work, I saw a directness, emotional intelligence, and autobiographical content, which greatly appealed and was very different from the outsider artists, which until then was the only form of expressive, untamed work I had found interesting. In her I had found an artist with whom I shared affinity, one who when she drew or stitched a line really felt it, it was not merely a rendition as much art is. I love the organic, biological, otherworldliness of her work and installations.

SS: You seem to be referring to later phase of her work, when she threw away ideology and produced complex work like Precious liquids (1992, Centre George Pompidou, Paris) or Maman (1999, cast 2003). You share with her the ability to make disparate materials work together. The former included cedar wood, embroidery, lights, metal, glass, tissues, water and alabaster, the latter combined bronze, stainless steel and marble. Your art manifests as installations with sculpted, woven and written details. Do you start from the spatial organisation and make decisions as to what goes where? Or do you make the elements first and when placing them in the given space you keep adding new ones?

SMcK: My beginnings are always with words, which lead to sketches, and plans, which materialise at early stage as concepts for pieces within a constructed environment. I see sculptures with their lighting as a stage for a certain mood I want to evoke. I often have ideas a long time before I find the right space. I seek out underground spaces and those which can be manipulated to cocoon the work. The ideas are developed to fit the specific space, often reinforcing its own personality. As I visit spaces, I can add to or omit ideas, pieces, or change them to suit possibilities or restrictions of the space.

I have used non-gallery spaces before when they have a particular quality, which will lend itself to my work. For example in 2005, I did an installation in Lagan Weir, Belfast, after finally gaining access to the chambers under the river Lagan. I was particularly keen to work there because of its closeness to the water, water which is habitat to seaweed. I needed very large spaces into which to incorporate natural elements and the changing states of seaweed. It gave me an environment close to replicating the seaweed on shore as it dried before the sea washed over it and so started another cycle. In the Lagan Weir there was flooding when tides were high or heavy rain and the seaweed was wet, and then dried out. In a sense, this environment preserved the material. It was also a suitably dark space, which involved a journey down flights of steel stairs, leaving you with a sense of discovery of the hidden, and expectation of what was around the next corner. Spaces have to be suitable for sound too, which is part of my installations. The space also has to be agreeable to lighting being installed.

SS: I am aware that your installations offer the transforming power and also joy of illusion. I perceive your art as positioned near neurology. Beside the view advanced by Semir Zeki, who perceives all artists as neurologists, you were motivated by personal experience. I think about the transformation you have achieved in the Lagan Weir installation. How did you make those ‘nets’, which worked like sculptures with the seaweed details shining like jewels?

My memory of it is not accurate; however, two kinds of objects still stand out: the lights and the writing.

SMcK: Yes, Slavka, in my installations I aim to put universal emotions into some kind of physical possession and offer them to the audience. I want them to feel involved in the environment and feel a sense of otherworldliness, transformation, becoming detached from the distractions of everyday living in order to feel pure emotion. I employ all the senses, using sound, light, texture, word to manipulate internal responses. My work is rooted in neurology as the key to understanding the operation of our own minds and where ideas come from, the mechanisms of thinking and communicating, or when systems are failing; the resulting state of non-being or breakdown.

I think Semir Zeki has an interesting outlook in his analysis of artists’ practice, how their perception arises in different brain regions and things like that, but he still addresses it in very practical terms. My interest is wider, with an all-round outlook at behaviour and most closely the resulting emotions and the power both destructive and enriching that this internal world harbours.

My neurological research and insight is closely related to personal experience. I have never directly discussed this aspect of the work, as I feared being labelled with any ideas of my work being related to art therapy. At this stage of my artistic practice, it is okay to reveal these inner truths. Throughout my work, from drawing, prints, writings, to performance and installation, clear links could be made.

SS: Sizing thoughts (2004, Golden Thread Gallery, Belfast) introduced seaweed in a number of forms.. You have commissioned a soundtrack by Susan Enan so gentle that it felt like the proverbial touch of the wing of the butterfly. You have put it even better when you wrote “The installation is about thinking and not thinking – the times when we barely exist beyond our outer frames...”

Next – the seaweed played one of the protagonists in the installation under the Lagan Weir …

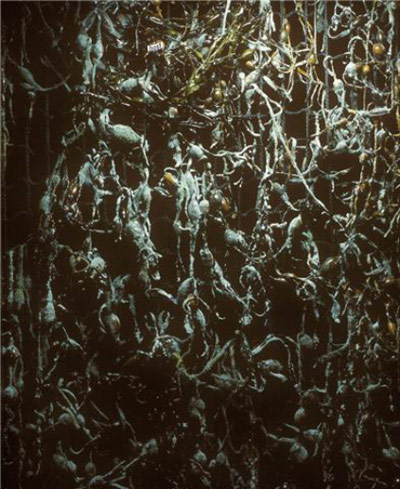

SMcK: The Lagan weir exhibition called Preserves of the minds larder was held in August 2005. The titles of the individual pieces were conceived as parts of a whole. Titles are a very important part of the work. I began work on this exhibition early 2004. One room was home to three large neuron sculptures which I called Budding thoughts (a nail in your coffin). Another room had two long scrolls of perspex writings and drawings, which I called Unravelling mind (thinking not and thinking lots scrolls). The seaweed nets, Walls of the mind, had individual characteristics; one called a Mindful had a perspex window sewn into the net and carried many more seaweed pieces than the other, representing too many thoughts, and also regeneration of neurons after injury. Another was in decay, with rotting seaweed used as nature’s equivalent.

The nets in Walls of the mind were 6m high x 1m wide, hanging from the roof of the chamber. I worked on them in my studio for many months. Firstly, I gathered bin bags full of knotted wrack seaweed. Next, I trimmed all the excess bits off each length of seaweed, to leave only the long body stems with round buds on them. Whilst I work in batches, at a certain point in the drying stage I varnished them with a heavy lacquer by dipping them in buckets and hung them to dry.

I then attached the seaweed, on one net at a time, initially by stitching them, then by weaving the seaweed in and out of the net to obscure it. I was not trying to totally hide the nets as they lent themselves to the idea of thoughts being trapped like things caught in the nets in the sea. I had black nets of a particular gauge size made by a company in Lisburn. Some nets were sparser than others.

The Decaying walls were made by using thinner varnish on the seaweed, so that during the course of the exhibition they began to go soft and to grow mould, eventually turning to dust and expiring. The seaweed with heavy varnish remains to this day as shinny, hard forms. Some of the individual pods on the nets had tiny typed words stuck on them, such as ‘neural networks’, ‘host’, ‘the leaving’, which were indicative of the state of that particular net, Wall of mind. I then used UV lights to lift those details out in the dark environment with no daylight. I wanted things to have an overall glow of blue and white light, which is the colour of electrical impulses in the brain when seen in brain-imaging scans.

The use of lighting is an integral part of my installations, giving life and guiding the emotional pitch. I have the lighting made and installed for each exhibition once I have gauged the strength of lighting, colour needs, mood that I need. Often when I sketch a sculpture, the lighting ideas come alongside it, rather than installing pieces, then sticking a spotlight on it. Light is a part of a piece of sculpture if it is to be seen to full capacity.

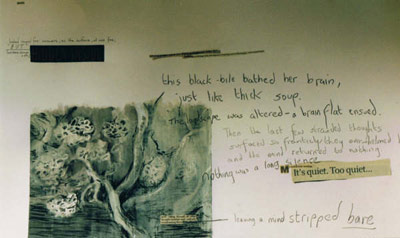

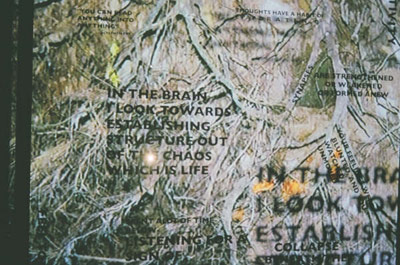

Writing is part of my work from the early stages to its final execution within the installations, performances, prints. In Walls of thought I wrote alongside it this passage of text: when an accumulation of neurons; thoughts themselves flooded the cavities in your head.

Preserves of the mind’s larder are observations in ‘all or nothingness’. I displayed two scrolls with a combination of my own writing and extracts from neuroscience psychology texts about the brain, neurological injury, psychological trauma, fear, elation, illness, impending death, etc. It is all very internally focused but with reference to nature and external influences; prescription for living from other people. I think of the words in my work as instigators, a quest towards a deeper understanding, or I use them as ammunition, deflecting pain. Sometimes they bring things back into a universal notion of existence. The writing is also used and incorporated into the music and in my invitations which are mini-sculptures with words incorporated. Each one is different, with an extract of the installations; being and bearing a part of the story.

SS: You have sent me such a mini-sculpture wrapped in soft foam: three ‘pods’, each carrying a typed word: …think…a blur…moments – with an instruction to bring ‘this thought’, preserved at room temperature, to the preview. It made me smile, and to feel welcome, in some way cherished as an individual. I have thanked you then, but have not expressed my astonishment how you understand the riches of simplicity. Later you made a mini-sculpture in a matchbox called Thought. The pencil writing is now difficult to read, the charm of the black box that refuses to open is timeless.

The Lagan Weir installations were accompanied by sounds, composed by Thomas Conyngham. His music was also a part of your installation The Bowels of the mind (2008, Basement, Dundalk). Your love for music led to collaboration with Miguel A O Perez ( 2006, SARC, Belfast). I have missed both. I have only your invitation, a plastic bag with printed words, delivered by the Royal Mail with apology for damage.

Tell me, please, about the battle of the 28 identical aluminium pieces with 28 ceramic pieces…these are not identical? And about the other emotional dramas, like the evocative, inescapable image of melting organism in The Dead and the dying.

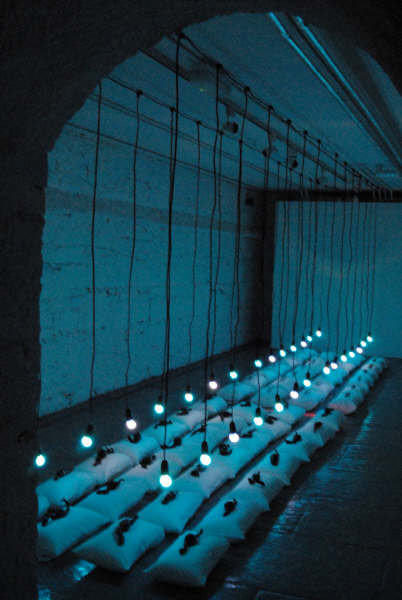

SMcK: In Lay you down on a bed of thoughts there is conflict between 28 ceramic thoughts and 28 sand-cast aluminium thoughts which have the word ‘indifferent’ impressed on their bodies. They were made to take on qualities of soldiers with straight bodies of polished silver, indifferent – all the same. I think of the saying ‘all the same now’. It is dedicated to all those who strive to be ‘normal’, follow the crowd and fit in; therefore they are indifferent, oblivious to the reality of what goes on around them. At the time I conceived them there was endless commentary on the nanny state and society’s control mechanisms. The opposing army (black ceramics) were personifications of ideas concerned, for example, with aging, breakdown, or feeling to be overburdened or experiencing a high. Some represented physical differences and injury, others psychological disharmony. The number 28 was because there are 28 men in an infantry section.

The music for this room by Thomas Conyngham was a voicing of each thought, with a definition of the word on the label the thought held. Each of the 56 thoughts lay on a mini white pillow with a blue bulb above it; in between the two sides was the battle line created with a red laser beam. The blue of the lighting was a reflection on the colour electrical impulses firing show up as in functional brain scans (FMRIs). To me it represents thinking alive as the physical self fails. People with anomalies (the ceramic thoughts) appear as the more interesting in this battle.

The Dead and the dying piece is sculpted from fine wire mesh with a stem containing Ibuprofen painkillers. It is housed in a bell jar with a red lightbulb. This piece is based on a medical diagram of a dying neuron with tangled threads in the central body as they appear in Alzheimer’s disease. I use it as a metaphor for depletion of mental capacity and memory. The Dead and the dying is part of an installation called The Endgame. In it were columns made of knotted wrack seaweed, weaved together into cylinder shapes like test tubes with blue lights in.

The Endgame was a stage, setting the bad things of The Dead and the dying against the seaweed constructions which showed strength, rebuilding, regenerating. I wanted to suggest hope to conquer illness and overcome difficulties, also to allow a restful feel to emanate from the installation. Together, they forge a link to the philosophy of positive things coming through experiencing the negative side of life.

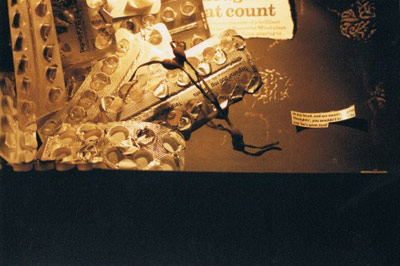

Another of the six-room installations in the exhibition was titled Ready for a fall. Seventeen pill packets cast in bronze were assembled like a house of cards, a common enough use of cards. Most of us have balanced cards standing upwards with great patience only to watch them tumble down. The title represents the expectation of a bleak future and preparing for it.

In The Bowels of the mind I hoped to induce some level of introspection in the audience, thinking or being seduced into stillness, while removing un-necessities for contemplative withdrawal.

It all culminated in constructing The Nothingness chamber inside the execution chamber of this former jail. Thousands of twigs, moss, and leaves lined the walls, roof, and covered the floor, turning the room into a forest habitat – restful with the smell of wood and sounds of leaves underfoot. This was a place with no dictate how to be; the inhabitant could be devoid of all emotion; internally silent or immersed in nature’s calm; and possibly, cleansed.

SS: In the age of consumerism and waste, your art calls for refutation of ‘unnecessity’. The ameliorative functions you embedded in the astonishingly beautiful materials, sounds, spatial relationship and, above all, light, do not allow the self – choice and self-making of the attentive viewer – to fall into triviality and incoherence.

In the age of intoxication with noise, speed and celebrity, your work makes calm, silence and reflective thought significant and desirable.

You have invented, echoing James Joyce, words like ‘pustulant’ for decaying thoughts and ‘thinkling’ for premature ones. While they describe a process favoured by our brain to obtain knowledge, they also sufficiently protect its mystery. That never shrivels to nothingness.

Slavka Sverakova is a writer on art.