SS: From your early work I recall three characteristics: charcoal drawing, use of various grounds and study of old masters. Later, you described your art made then as ‘construction / destruction’. Why?

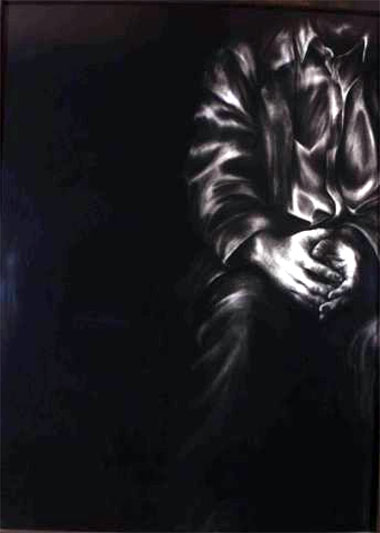

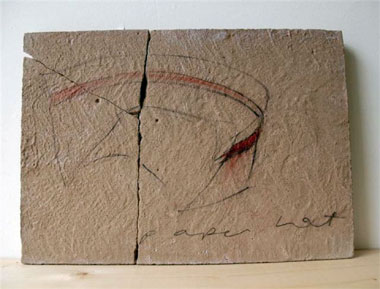

SK: I have attached two images from work made for the Masters show in 1989. One shows the full piece and the second a detail. The work was part of a large drawing installation approximately 10 feet high. This piece was 10 feet wide. It no longer exists.

Given that 20 years have passed since this was made, I can tell you what I remember of that time working. I could not afford expensive materials and worked with quite a basic palette (paper, canvas remnants, wood, clothing, white paint, charcoal, etc). I hardly ever used colour, preferring the natural colour of the material to be evident.

The inspiration for these pieces came from both within and from the world around me. Belfast in the late 1980s was a very different place to walk around and to live in. Destruction and decay and waste were visible every day. The fragility of life was very much in my mind. I thought about these things very much and about how being in the cocoon of the art college felt against the ‘outside world’ – if you looked out of those large college windows, another world faced you directly and yet some of the things that were being engaged with by some students and staff, during my life as art student, made no connection with that world.

On another level I was creating artwork, destroying its wholeness and fragmenting pieces, creating something else. The process was important. I also played with the idea of 2D and 3D space as these pieces existed on both levels, hovered over or were torn between spaces. I felt like that myself privately with the life of mother and art student and at the tail end of a very destructive relationship.

I called the entire piece Confirmation and denial . Small poetry texts were suspended on the windows written on tracing paper. I cannot remember what the words said.

SS: The two exhibitions of drawings, Dichotomy, 1992 and Lifting the Veil, 1994 / 5 are a direct expression of existential anguish, the drawings are immersed in the never-ending pain of losing an infant to death. The images walk a tightrope between scream and silence. The absences of parts of bodies or of whole bodies (eg, an empty chair) became eloquent and dignified witnesses of crossing over the threshold of Earthly life. As for the later group, The Tears of Things, its source of subjects is somewhat outside your personal experience. Your concern with the closure of a hospital seems dominant. Which of these images would you prefer to draw attention to?

SK: The series of drawings named originally Dichotomy, shown in Harmony Hill, 1992, was later shown in The National Maternity Hospital, Dublin 1994 – 5, in a year-long site-specific project, in which I re-titled the drawings: Lifting the Veil. Dichotomy and Lifting the Veil are essentially the same drawings.

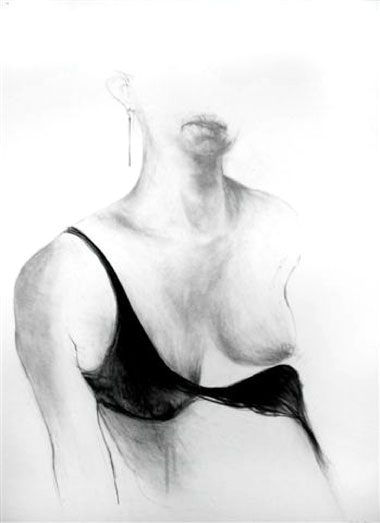

That early series is very important to me, personally, since they represent my struggle with dealing with the deaths of the infants. Traumatic events, which took place now some 18 years ago. An upbringing in a sense – bringing the child to adulthood time. There is the sense of the time having passed, yet, the absolute detail of the events remains raw. The body of work, Tears of Things, was conceived because of this fact of the passage of time and the workings of grief… I made those black charcoal drawings in the studio, 1992, with no original intention to exhibit them, they were made in private for me as a way of dealing with the intense emotion of that period. However, when they were exhibited, particularly in the National Maternity Hospital, Dublin for a year, their presence there took on a different energy. I always felt drawn to the two images Woman No 5 and Borne – especially when presented alongside each other . The space between the figures interests me.

In regard to the later work, there is a strong continuity of subject matter – loss. There is the personal loss which inspired the work, then there is the communal loss of a hospital and the end of an era for the midwifery and other medical staff. I created images which I hoped would forge a connection outside of my experience of the hospital, which was both positive and negative. I am interested in the layers of personal, universal, beginning, ending, creation, destruction, renewal; the nature of grief and existing. Of all the work then, I would draw focus towards Life drawing .

It was shown as part of a video installation, though it stands alone as a piece, since the sound originates from it. The work records the life of a drawing – an infant hospital cot – from white space to finished image and its reversal and includes the sound of demolition of the maternity hospital and the voices of mothers and midwives.

I chose to include the (Polaroid) image of my son, which appears and fades away during the creation of the cot image. I feel this piece in some way expressed my intentions for the body of work as a whole. Creating the piece provides a strong connection for film ideas with which I am presently engaged.

SS: Drawing is your dominant mode of work. However, during the 1990s you used sound (Hand to Mouth, 1993), photography and video (Still, 1998) as well as drawings. What attracted you to the lens based work and to the use of the sound?

SK: The idea for the use of sound in Hand to Mouth, 1993, came to me in a precious moment of breast-feeding my child, born after the sad events of the previous two years. The sound of her suckling at the breast and the image of the hand appeared in my head almost completely at the same time. I was now in that moment, nurturing new life, yet, through bereavement, felt compelled to consider not being – death – in the same instance. Sound is of time and I like these thoughts.

As for the lens-based works, these have been problematic for me. I began using photographic images / video images around 1993, however, I had used this medium to document material, particularly sound. So it felt like a natural move; however, much of the video and photographic work that I have encountered through exhibitions over the years disappoints me. I feel quite ambivalently towards these media – how they are often presented; the surroundings and situations where you are ‘passing through’. In regard to my own work using video, I much prefer that which records the drawn elements together with photographic imagery. Drawing Time 2002 / 3 and some of the work included in The Tears of Things come to mind.

Drawing Time was a work created during a three-year educational project with children, the pupils of Scoil Phádraig Naofa, Kilcurry, Dundalk. The idea of time passing and the lull and pace of school life was explored in various ways. This work, in collaboration with the children and their teacher, provided immense inspiration for later work also.

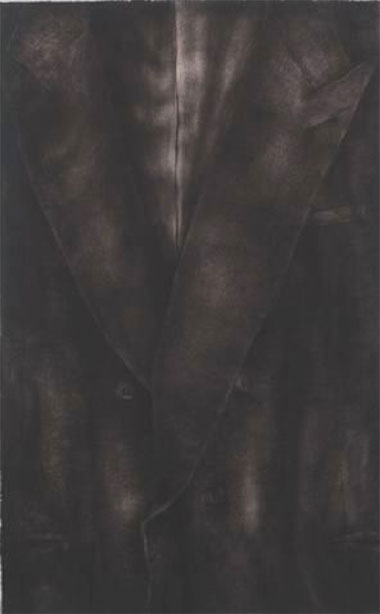

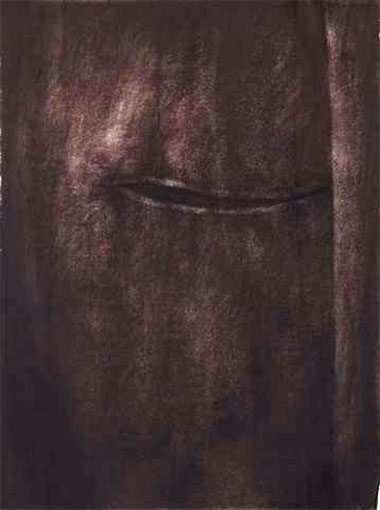

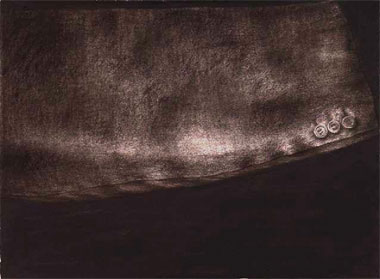

SS: Earlier you listed the ideas, or layers of them, upon which your art depends, for example the personal and universal, the interweaving of which I saw in the powerful charcoal self-portraits at the Fenderesky Gallery… two years ago? These images embodied Self as an object of a drawing – your observation was severely opposing any flattery. They and the drawings you’ve made of the hands of your father, or of his coat, o r of the uniform of your mother, present intimate feeling as an objective memory. The truth is very clearly your dominant value; in these drawings it protects the memory from being eroded by subjective sentimentality.

Is there also some other reason / inspiration for your choice of self–portrait and still life?

SK: I made a series of self portraits which were shown in the Fenderesky Gallery September 2004, made soon after The Tears of Things body of work.

These were about me being in the studio, with my thoughts and about the process of looking, reflecting on where I was, particularly after the emotional energy that the recent work had demanded. All these works were made in quick succession over about three weeks.

They were to do with thoughts and feelings; of having left youth behind, aging, experience and life.

I was not interested in the physical ‘look’ in the sense of describing an aging face, etc, but more to do with a person and a body that has experienced / lived through happiness and sadness and that it was OK and necessary to life. I think of Frida Kahlo and the sense that she recorded her own capacity to feel pain. It is not to do with self-pity but to do with connecting with humanity and what it is to be in the world.

The integration of the body image and the dress that features in the series (and I guess this idea has resonance in connection with the clothing drawings, uniforms, etc), has to do with memory, very personal – for instance that black linen dress, embroidered with colourful flowers, has been with me for almost 30 years.

I found it in a second-hand charity shop. I believe it was hand-made from a tablecloth, so it has a life history very rich before it was worn by me! Every year I wore the dress through the summer and it is now threadbare and fragile. I was recording it almost by every fibre, feeling it as it hung in my studio, as an act of both joy and defiance at its fading, but also acceptance of this as a law of life. For the process of drawing the suit and tools of my father after he died, the objects were, at the same time heavy with life / potent with something and yet completely inert as object.

There is a certain tension in this, which is where I feel their power lies. What is also important is the process of creating the work – observing and feeling.

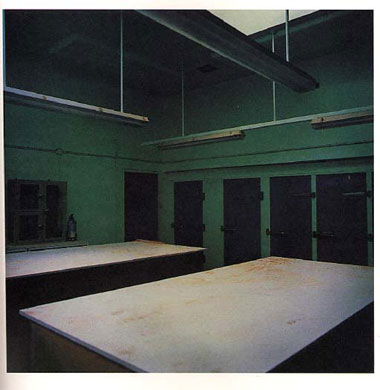

This leads me to the photograph of the mortuary, included in the Tears of Things body of work.

This particular photograph I knew I wanted to take and sought carefully to do this. It is behind the curtain, long after the event of the child being placed in the mortuary, yet there was a compulsion for me to record the remains of that place (it was also awaiting demolition) that was hidden from me at the time of my son’s death.

The self-portraits are perhaps a search for hidden spaces; the hand / clothing images are perhaps similarly so.

I cannot adequately describe the process that happens after the images are made.

SS: Both the portraits of things and of a woman keep the sense of dignity, honesty and authenticity so apparently absent from many ideological and political agendas.Whatever it is we call creative process is and must stay tacit. At present – you work on films? What kind of films?

SK:I have been nurturing an idea for a film for some time. It has evolved from the themes of memory and loss with which I have been engaged with since the early ’90s. It is at a very early stage, experimenting with ideas and opening dialogues with those in the film industry. My vision is for a poetic engagement with the theme of artistic response to communal and personal loss. So it will centre on the creative process.

The process of observation and feeling urges this forward. It is also my intention to create a work which has more of a lasting life than I witness with staging video installations. These have a very limited life as work to be fully engaged with. You encounter it often in art context / gallery / public location; however, I have never, ever felt satisfied with this, either with work I have presented or with video work of other artists.

After this staging of the work what is left but a documentation, sometimes in a book with a plethora of mindless text, sometimes not and it loses significantly. I prefer something else which has the power to draw you in and allow something slowly to be revealed over time. It is a project that will engage me for some time to come.

Slavka Sverakova is a writer on art.