At Cork Airport, one is welcomed, not by a real aeroplane, but one formed from topiary and, for added realism, a strip of painted windows. It is one of Cork’s more significant pieces of public art, protected by CCTV . This story begins and ends at this roundabout; however, to get there requires a digression, one in which you will get lunch along the way.

Cork, in winter, is when airlines’ discriminatory schedules mean a long day of travel to get to and from the south of France. Luckily my flight from Cork provided time to contemplate that word ‘discriminatory’ in both its meanings. Maybe these musings were inspired by the in-flight culinary reading of AA Gill, who described Gordon Ramsay as “like Ronald McDonald without the dress sense…” Gill amused me further by explaining that Ramsay’s restaurant, named Foxtrot Oscar, refers to F.O., the initials for the radio operators’ international alphabet. Apparently Foxtrot Oscar is a nice way of calling your eatery Fuck Off .

I was in Nice to arrange the return of my monumental sculpture from MAMAC, a national French museum with an international collection that exhibited the five-ton bronze Cow up a tree juxtaposed against their large Alexander Calder and Nikki de Saint Phalle. I had also arranged to meet some good friends and decided to take them to lunch at Bar d’Antoine, a typical French Bistrot run by a lovely Portuguese couple on the Rue de la Préfecture.

Before we eat, let me introduce you to my four friends who are joining us for lunch. John is an Australian filmmaker. Paul is English and a psychologist, married to Virginie, a French banker. Then there is Glen, an American mercenary who divides his time between Nice, Afghanistan and Iraq. The five of us were seated upstairs next to some local Vieux Nice (old town) clientele, which is always a good sign when eating in France. On the stairs we were entertained by a humorous painting of Nicolas Sarkozy dressed as Napoleon, whilst behind me a French Madame had her Mandarina Duck handbag strung from the back of her chair, from which the head of a tiny French lapdog was visible. After the obligatory French champagne we decided on a rosé (Domaine Colombette 2006, Côte de Provence – 21 euro). Rosé is a wine which connoisseurs often unfairly discriminate against.

As our entrées arrived, Paul (moules – 10 euro) was informing us how a Russian miner performed the first lobotomy: he prematurely detonated his dynamite, sending a steel rod through his temple. The miner, who before this accident was always unhappy and agitated, survived and upon recovery had a complete change of self and was actually contented! This entrée subject was arrived at through Paul telling Glen (petite caille, lentilles, riquette, fois gras – 10 euro) and John (no entrée) that the need to conform in bureaucracies can lead to a lobotomized organization, meaning one whose creativity has become ‘contented’ through the organisation’s ceasing to think. Paul went on to explain that corporations now counteract this by offering prizes to the public in exchange for ideas, which they can then commercialize.

As the asperges vertes, lard paysan and salade de mâche (8 euro) vanished from my and Virginie’s plates, the idea of a prize being offered reminded me of a recent e-mail received from Cork’s National Sculpture Factory (NSF). I explained to my friends how three public commissions had recently been announced, one of which was an ‘open’ solely for Cork-based artists. It offered 5,000 euro. Before I could go further, Paul interrupted with “exactly, that is a great way to come up with new ideas for a public artwork. You put up a prize and all these artists do this free work and you choose the best one. It works for corporations because lots of people have great ideas; however, the problem is, very few can realize them because they do not have the resources to make them happen. Organizations on the other hand have the resources but being bureaucracies, often lack the ability to think.”

Quaffing the rosé, I suggested it might be worth looking at how art organizations have evolved, because they have been using this model for years.

The main course arrived, which for Virginie was cod, with potato mashed together with more cod (cabillaud frais, brandade de morue – 14 euro) with an alfalfa and radish topping, which she said was just simply divine. John having foregone the asparagus and bacon entrée, had it as a main; however, he was disappointed to receive an entrée portion and, as he did not speak French, he could not argue. I went for the meatier banquet of duck (magret de canard grillé – 12 euro), on which I nearly choked when I related to my friends the NSF’s correspondence on these commissions.

I explained that according to the NSF, originally there were only two commissions planned, one being for an international artist and the other a national artist but, having been made aware of the lack of opportunities for local artists (they had not noticed!), they decided to stretch the budget to include a commission for a Cork artist. I explained to the table how three discriminatory models were to be used to select each artist. However, the Cork-based commission was to be less than the others because it was meant to simply allow them to realize a good idea with “cheap or ephemeral materials.”

As I spoke these words, Glen kindly whacked my back to dislodge the words cheap and ephemeral from my throat, which distracted him from his steak (entrecôte grillée – 16 euro) and accidentally sent his steak knife flying across the room, noiselessly lodging into the Mandarina Duck (1,500 euro). Luckily, the owner did not notice as she was devouring the mousse au chocolat (6 euro) and did not even turn around to see if I was OK. We later learned the mousse really was worth the attention.

After the commotion settled down, I managed to explain that the NSF’s role is to assist artists from Cork and Ireland and not be discriminatory in the way they do it. My guests were suitably amazed that an arts organisation would reveal publicly, and in writing, that not only are their local artists an afterthought, but that the organization is happy to discriminate against them based on where they are from. As Paul tucked into the grilled veal kidneys (rognons de veau grillés – 13 euro), he asked about the different commissioning models used, so in my increasingly inebriated state I related how they werespecifically choosing the international artist as an outsider that could bring “a fresh perspective and introduce new practice” to Ireland.Paul was curious and asked “how they would select an international artist from the millions of them out there?” Would the selection panel undertake a worldwide visit of studios? Or would they be wined and dined by the galleries of London and New York, so as to get a full understanding of this fresh new perspective that had escaped Cork’s attention? I replied that it was more likely to be ordered straight out of a catalogue, much as one buys from Argos. For only the most unthinking organisation could take a selection panel on an international shopping spree when they can’t even afford to support their own constituency.

On the other hand, the three national artists were asked to put forward submissions from which only one will be chosen.. This was a bit like choosing between Bar Antoine’s three desserts. All good but two would be rejected.

As the desserts were placed before us, I explained to my friends that the problem is that I am a mid-career artist exhibiting internationally, but unfortunately I live in Cork, which seems to exclude me from these commissions. Paul seemed to think that having an international reputation would automatically give me a national Irish one. Virginie disagreed, saying I had a national French reputation but not an Irish national reputation, because I have only had one exhibition in Cork, and whilst I have shown in Paris, that is the French national capital, not Ireland’s. She had a point, as Glen and Paul agreed. Glen stated that I had never made any money from arts organisations, so I should stop wasting my fucking time. John, who was still hungry and irritable, used the distraction to eat his tarte aux pommes (6 euro).

“That’s not my problem” – I interjected. “I have not been selected in either the international or national categories, but I could still enter the ‘open’, couldn’t I? However, if I did, should I be prepared to be discriminated against or should I demand to be paid the international or even the national rate of remuneration as set by the NSF?

Paul suggested I was becoming obsessed with an unhealthy desire to confront arts bureaucracies who had the best of intentions, and I could see my other friends tiring of this debate. I retreated into the lightest mousse I had ever tasted (mousse au chocolat – 6 euro). I am sure Virginie noticed my change of mood and, whilst Paul excused himself to make a phone call, she asked why I had left Australia in the first place. “Very complex,” I replied. “I thought it was the tax,” the still-famished John interjected.

Look, part of the reason was that Australian art institutions slavishly imported the international at the expense of the local. The reason being touted usually revolved around a historical need to educate us dumb Aussies because we were unable to travel to Europe, which in this easyjet era seems to have far less validity. For example, only a few years ago the National Gallery of Victoria (which is not a national gallery, by the way) spent over a half a million dollars on one painting by an elderly decorative British abstract artist when its contemporary Australian art budget for that year was $30,000Aud. It might be deduced that international travel and the advancement of curatorial agendas rather than fostering and caring for local talent were seen as higher priorities. Therefore I took the late-nineteenth-century Australian writer Henry Lawson’s advice, which was –

My advice to any young Australian writer [artist] whose talents

have been recognised would be to do steerage,

stow away, swim, and seek London, Yankeeland,

or Timbuctoo – rather than stay in Australia till

his genius turns to gall, or beer. Or, failing this –

and still in the interests of human nature

and literature – to study elementary anatomy,

especially as it applies to the cranium, and then

shoot himself carefully with the aid of a looking glass.

So rather than giving myself a lobotomy, I left.

Coffee orders were taken and I was the only one who ordered a glass of red (Verrerie Bastide 2004 Côtes du Luberon – 7 euro). John suggested using the 5,000-euro commission to sail away from Cork Docklands for a number of months to an international destination (like Bar Antoine). If the NSF had not noticed Cork artists in the first place, it would not notice one missing and it was cheap and ephemeral!

It was at this time that the lady at the next table noticed the blood oozing from her Mandarina Duck and screamed. The shock of it made me panic and I stood up and screamed back at her: “ALL RIGHT – I will have the operation. I will buy a gun and a looking glass and do it myself.” Glen said that he would do it for me! I didn’t care any more, all I wanted was to stop being agitated by the discriminatory practices of an organization that I am a life member of. The dog lady was also agitated and threw her handbag, including dead dog and steak knife (couteau et chien mort) at me, upon which I ducked (magret de canard grillé – 12 euro) and Glen took it in the back of the head. As he went down I heard his Texan drawl say ‘Foxtrot Yankee John.’

Glen hit the floor with a thud, whilst I caught sight of Paul talking to two chefs on the way up, both resplendent in their white coats. It seemed OK at first as they wheeled the cheese trolley towards me, but when they manhandled me onto it I finally understood their intention. I sat up and in my best French tried to explain that the dead dog was an accident. As they tied me down, I told them in English to Foxtrot Oscar but they bounced me roughly down the stairs past the Napoleonic Sarkozy (who winked at me) and into the waiting Samu (ambulance). As the dead dog landed on my chest and the doors slammed shut, I asked the now obvious chef impersonator what terrorist organisation was kidnapping me? “La Nationalistic Sculptural Front you roast beef.” All I managed was “I’m Irish you langer” before the guy injected me with what drug I know not. Luckily, before I passed out, my last sensation was the feeling of the Verrerie Bastide crossing from the frontal lobes on the way to my thalamus.

My next recollection was of being woken by a stewardess on a plane at Cork Airport. As I disembarked, I heard the Cabin Service Director (CSD) whisper (a little too loudly) to the smiling first officer standing in front of the open cockpit door, “Foxtrot Mike Romeo?” Then the CSD turned and winked at me, causing me to fall down the stairs and I literally kissed the tarmac. Picking myself up, the wet Cork tarmac washed away all that Nice fucking duck taste. Christina, who was waiting patiently (food and car park – 180 euro), greeted me warmly before we drove off. As we circled that ‘hedge’ aeroplane with the painted windows she asked, “how did you get on with the sculpture and MAMAC?” “Sculpture – what sculpture??” I replied.

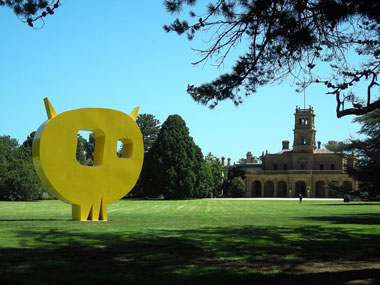

John Kelly is an artist based in County Cork. He is represented by Agnews in London Niagara Galleries in Australia. His work can be viewed at the Fenton Gallery in Cork. Until May his sculpture Cow up a Tree is on exhibition at MAMAC (Musée d’Art Moderne et Contemporain) in Nice and Yellow peril (square eyes) is a finalist in the Lempriere Sculpture Award in Australia.

Bar d’Antoine

Rue de la Préfecture

Vieux Nice

Lunch with wine for five – 180 euro