S: For a more than a decade you have been dividing your energy between your art practice, teaching art and family life with Patricia, two daughters and the recently arriving Mark. I observed you with your family the other day in the newly open Ulster Museum, an air of quiet confidence around you all.

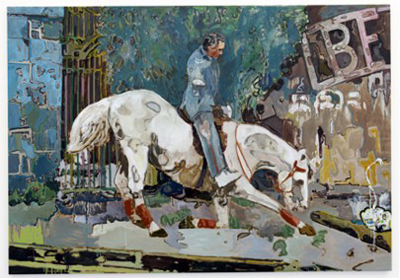

I recalled another kind of confidence expressed once in a public debate in the old Golden Thread Gallery about being a significant painter. The strongest indication of what that may be was the exhibition at the Third Space in 2009.

In your response to my inviting you to have this exchange with me you e-mailed me a whole alphabet of points, ideas, concerns, memories and observations.

This is how it starts:

DMcK:

My ‘a to z’ of painting and drawing, second version, 24.10.09

(If it were possible to convince of the ‘learning aims and objectives’ of this activity, I would put it into the studio curriculum for my students. It is a great way to clarify what is important in work, and can be adapted every few weeks.)

SS: I trust the inspiring elements of fragments that are rooted in the real life of a painter, especially, as you grant them the fluency of change. A fragment like this one.

DMcK:

A: accent in painting is always there, but working in a different way from speaking. I am always struck by how much painters sound and look like their paintings.

SS: Supported by my own experience that reading a drawing or painting as a map of the artist’s ethos is perfectly admissible. Visual force never told me any lies, even if the authors did. My reading happened in silence, it was a mute exchange, where you think of the similarity between the visual and the verbal, the visual and the audible.

Your use of the word ‘accent’ in relation to the individual’s identity and ethos brings forth an altogether more exciting layer of thoughts. It is often connected to 20th century abstraction, although it is visibly there in all drawings and paintings – good or bad. It includes not only composition and its centre or centres, but also the relationship of the key to a rhythm, of hues to the mark, its size and visibility.

Can a source imprint as an accent?

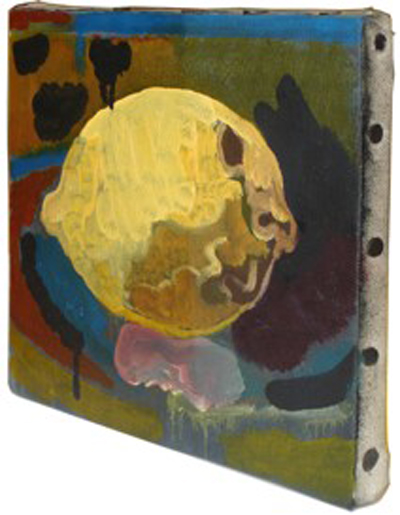

In a playful analogy – your painting of the lemon(2009), has it a French accent?

Moreover, under the letter L of your art alphabet is a reference to it.

DMcK:

L: lemons. I painted one recently, from a reproduction of a Manet painting.

As far as French painting goes, Manet I got interested in for other reasons. It was connected with his decision to stay on in Paris during the siege of the Franco-Prussian War, which some of my recent work has revolved around. Degas stayed too, Bazille was killed in action. Most others fled – Monet for instance, only 30 at the time, Courbet and the writer Zola, all left for safer refuges. Manet sat it out in his apartment, hunted around and found a photograph of his wife to keep himself company (we know this from his letters to her, flown out by balloon during the siege), and along with Degas served with the National Guard. Manet’s Lemon painting, and his Asparagus paintings, I have always been fascinated by. He painted them a decade or so after the siege. To think that during the siege, the Paris Zoo elephants (Castor and Pollux) were shot for food, and rat also became a staple – Manet must have reflected on this as he painted those little still lifes. On a formal level, my own lemon went a bit misshapen, so I thought it would look better at an angle. When it ‘hangs’ on the wall it has a hinge at one side so that the painting can be pulled-out from the wall. This ties-in with Manet’s uses of perspective, I think (and photography for that matter – I have read that early flash-photography and the pictorial ‘flatness’ of shadows this created influenced the look of his work.)

I have always liked the Nabis painters – Vuillard and Bonnard (and Vallotton, who is very overlooked). I happen to use French-made oil paint – great colours made by Sennelier. Vuillard and Bonnard often used photography as a source for their paintings, and this too has been one of my main areas of interest in recent times – painters’ uses of photo-generated imagery. Many current painters are using it as a source in original and different ways. Close to home, Mark O’Kelly and Elizabeth Magill for instance. Further afield – Daniel Richter and Sabine Dehnel. It is a very different relationship painting has to photography now, compared to, say, when Gerhard Richter, early Malcolm Morley or Chuck Close commented on it. It is now being utilised in much more diverse ways in painting – it’s certainly not about making photo-realist paintings anymore.

SS: Edouard Manet has been credited with the role of a founder of Modernism at the time when plein-air painting was well established and contrasted with the academicism. Painting at that time escaped historicism and still kept its dominant role in visual culture, although some cries of the death of paintings were heard too. Your concern about the position of painting, the “mute poetry" (Leonardo), became expressed in your ‘alphabet’ under letter H.

DMCK:

H: hinterland, the place where painting is in relation to art at different times. High Renaissance (except Titian) and the Baroque period (except Rubens) for instance. Bosch and Breughel are also real ‘hinterland’ painters. Painting has not been in the hinterland of art recently, however.

SS: On reading it, I still fail to follow its meaning fully. On what ground you determine the place of painting in the rest of culture?

DMcK: I’m getting at the fact that the idea of the ‘end of painting’, of its anachronistic nature in relation to other contemporary ways of making art – well, it seems to me that this has always been the case at different points in art history. When this happens, really new ways of painting come to the fore. So, painting was there of course in the Renaissance, but that was really more a time for architecture and sculpture, and poetry and engineering – all the other stuff Michelangelo and Leonardo were also doing. Nothing particularly ground-breaking about their paintings, though, I feel – the time for ‘new’ painting had happened in the Early Renaissance with Giotto and Masaccio. Titian makes painting important and new again. When I first got into art as a boy I used to go to the National Gallery in Edinburgh a lot, where I could see the two Titians that have been in the news recently. I was able to look at how he used paint in so many different ways, the virtuosity was in this. Across the way there was Velázquez’s Old woman cooking eggs – this to me was more about paint and the illusionism of ‘reality’ – a fantastic painting, but somehow less ‘painterly’ than Titian’s work.

To come back to your point about twentieth-century abstraction – it is often said that this was when paint itself becomes the subject of art, particularly in Abstract Expressionism. Whilst we cannot exactly talk about Titian’s work in those same terms, I find it hard to believe that viewers of his work, in his time, were not amazed by the paint quality. That he sometimes supposedly used his fingers to paint with also ties him much more to ‘gestural’ painting and expression. Back to my ‘hinterland’ point – in the Baroque period, again it’s all dominated by amazing architecture and sculpture – Bernini perhaps at its pinnacle – and again it takes a painter like Rubens to make a unique statement within all of this, through painting alone. (Of course, there was nothing ‘hinterland’ about Titian’s and Rubens’ other positions – their influence as artists was very much tied to their involvement with the authorities of the church and the royal court.) I mention Bosch and Breughel because they are working at a time when most artists are painting classical/ mythological and religious themes, whether in Italy or other parts of Europe, but they’re doing proto-surreal and peasant paintings! Even now their work is in the hinterland of our culture, so beloved are they of the teenage heavy metal fan! Painting as a main part of art culture comes and goes, but there are always ways to re-vision and renew its place within the general culture of its time. The English painter Nigel Cooke does this really well just now, he has a great process going on with his ideas and materials. But perhaps, in the main, painters get too defensive about their practice. So, for instance, I’ve just been checking out an exhibition called Painting under attack which was on at the Seattle Art Museum recently (it has a wonderful interactive part to the exhibition website, worth checking out!). It’s a provocative title, as it suggests a defensive position. But in fact the exhibition looks at the ways in which some artists interrogated the nature of painting practice from 1949 – 1978, so the title actually relates more to the way some painters ‘attacked’ their own paintings, not to how it was under attack from outside. But on the other hand, it does also suggest a hinterland position for ‘image’-based painting at this time.

SS. To place painting in the hinterland – such a desire and effort connects to both instrumental and intrinsic values of art. I wholeheartedly agree with your P in the second version of the alphabet:

DMcK:

P: ‘please the viewer’ is really what funding bodies mean by ‘audience development’. It is the last thing on a painter’s mind.

SS: In general, far too many people distrust reverie, imagination, inventive changes – in essence for fear of insecure feeling or thought, they feel threatened by uncertainty and difference. Fear crumbles their innate courage and individual responsibility. In essence – art has to do the exact opposite. In this I perceive its instrumental value, not in a service to an ideology, a dominant context or a ruling body. On the most banal level, people cannot look at the visual arts without first reading up what they are supposed to see. Allowing a keyless viewer to enjoy discovery in the intimate and direct encounter in or out of context is instrumental value par excellence. Moreover, neurology is capable of measuring it.

On the other hand, people respond well to sub-stories, like your letter B,O, Q, T, R, and S.:

DMcK:

B: Bonnard Blue made by Sennelier, also called English Blue. I perceive it to be a ‘new’ colour, almost not blue at all, neither cool nor warm.

O: orange – difficult to find the right one for my palette, but Indian Yellow Orange comes close, as it’s a brownish/ yellow orange.

Q: quick start with all my paintings, including the blocking-in. Start at the middle and move outwards to each corner. Bonnard worked something like this, Seamus Harahan told me quite recently.

T: testing-out ideas and really trying to pin them down, in drawing, has become more important for me over the last year or so, inspired by Mark McGreevy in particular.

R: relax with a coffee, before painting.

S: Scot, being one – always in the background for me, but I don’t know how significant this is.

W: washing and cleaning of brushes and palette is a big part of my ‘leaving the studio’ routine.

SS: Turning to the intrinsic value – that is difficult to describe and grasp, but not difficult to experience. Any aesthetic experience contains a cognitive element, and a massive dose of imagination. Baudelaire called imagination the “queen of the faculties." In your alphabet letters E, F, J, K and X, and V illuminate best your map of those things.

DMcK:

E: evening light, as described by Thomas Hardy near the beginning of Return of the native. I think about his description when painting in the studio.

F: failure must be expected in most paintings you make, but not in drawings.

J: Jewish music, and ‘Jewish sounding’ music, I find very moving. Is this a cliché? Also a big fan of Chagall…

K: …and Kitaj, R.B.

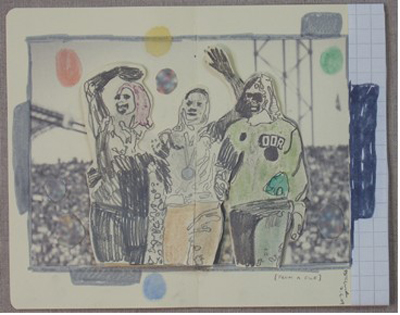

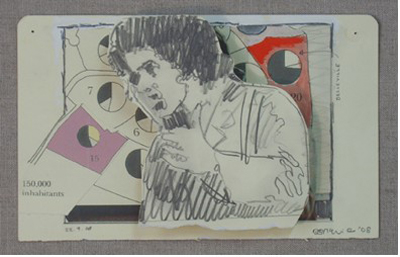

V: Viren (Lasse), the Finnish runner, has become a topic in my drawings recently. A really iconic figure in athletics in the 1970s, he always crossed the line with his arms outstretched in a most Christ-like way (see ‘X’). My Dad always talked about him.

X: crosses in compositions are useful, always thinking of how vertical and horizontal elements interact. (See ‘Z’ as well.)

Z: ‘Xanadu’- I have been memorising the beginning of Samuel Taylor Coleridge’s poem Kubla Khan. Begun quickly after an opium-induced dream, it was interrupted when someone called to see him. He completed it later in a more sketchy way, having lost his train of thought. It is still an incredibly visual poem.

G: good sleep, easily achieved by thinking about what must be done next time in a painting.

I: international – good to keep an eye on events and developments in the news. The Financial Times I prefer, with its pink paper.

M: music in the studio, or its place in an artist’s working methods, is definitely a cliché. It is the only aspect of Peter Doig’s work I am not interested in.

N: the nuclear age. I am surprised at how much it has been pushed from our minds.

U: underground travel. The thing I like most when I go to a big city.

Y: yellow – see ‘L’.

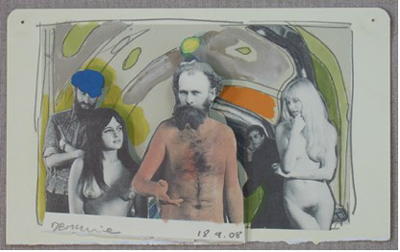

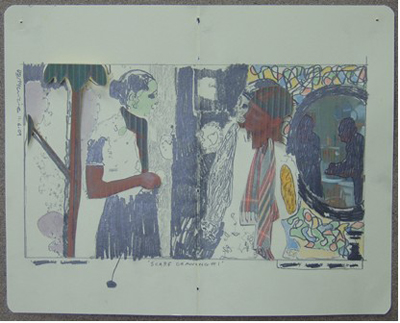

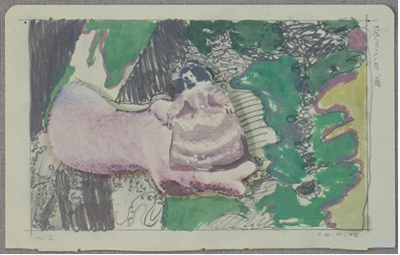

SS: The images that accompany our words possess maturity and gravitas, and allow for a touching appearance of humour and poesis. I read Donald Kuspit (again). He thinks that contemporary visual art is not art but post art, and that only New Old Masters could turn it around.

Your musing on hinterland connects to the position painting may have in that process, in the renewal of visual art, of visual force. Painting is the “mute poetry" of Leonardo, and the supreme domain for imagination, which Baudelaire cast into the Queen of all Faculties. I am convinced that your images, painted, drawn or collaged, contain qualities which cannot be obtained otherwise. You connect your images to social history, to art history, to other parts of visual culture, but you do not imprison them in or by any of them.

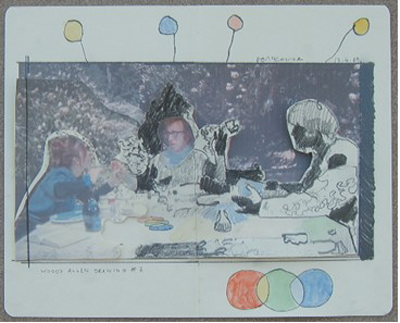

Do you find it easy not to subscribe to one ideology?

DMcK: I have looked a bit now at Donald Kuspit after you mentioned him. In fact, a Google image of him has gone into my computer folder, one from maybe the ’70s / 80s- he has the look of a Woody Allen character about him, and as I’ve been using a few still images from his films, Kuspit could be cropping up somewhere in my drawing soon! He seems to me to be making a lot of valid points in interviews I’ve found, discussing his book The End of Art, although I have to say his citing of Lucien Freud and Jenny Saville as ‘New Old Masters’ is not moving painting out of the hinterland, for me at least. Howard Hodgkin and Cecily Brown would fit that description for me better. What he says in another lecture of his, attacking Gerhard Richter, I completely agree with. In the good old days when there were quite a number of South Bank Shows on TV about painters, the one on Gerhard Richter was such a bore – spotless, chrome-finished studio and house with (incredibly) his children/ grandchildren? dutifully playing chess to fit in with the look of everything. Such a contrast with an earlier one on Francis Bacon, with him and Melvyn Bragg enjoying a good meal and drink, and getting quite giddy talking about Michelangelo.

Okay, you could say one fits the stereotype of a painter as much as the other, and both knew the game that had to be played to succeed in the art market. They just took it on in different ways.

However, I find some of Kuspit’s other ideas very retrograde. This is underlined by the artists he selected for his show California New Old Masters in 2005. In the main, neo-classical inspired figurative work – all ‘craft and technique’ and low on ideas. Just not of our time at all.

You asked me about ideology – I am most interested in artists whose work creates interesting visual dialogues with the culture and society of their time. Certainly, they are very often immersed in looking back to art/ historical references (like Kitaj did, and I also like to do), but try to avoid getting trapped too much by that. We are each hemmed-in enough by history in our everyday lives. Painting should be looking to unpick the stitches of that predicament.

SS: Well put. Thank you. Painting’s power to do the ‘impossible’ (eg Magritte’s flying stone) indeed makes it the most suitable candidate to explore different ways of relating continuity with a rupture, relating old art to the one that is to be made. However, I heed here Karl Popper’s warning about the pitfalls of prediction as well as of rhythm, patterns, laws and trends.

Slavka Sverakova is a writer on art.