Regina Gleeson has been in conversation with Katie Holten, Ireland’s representative at the 50 th Venice Biennale, 2003.

– Your work in Venice is particularly interesting because of its being a node in a creative and intellectual network of multi-disciplinary exploration. Can you talk a little about your route to this mode of working or your reasons for choosing to act as a director of this catalytic collaboration rather than the single producer of the project’s contents?

I’ve been working collaboratively since 1997. I founded the Tûp Institute which, from the beginning, functioned as an instigator and facilitator of public art projects. Specifically temporary, no-budget, unofficial events. In 1997-1999 I was working with an artists group called PLUG (I was a founder member while in Berlin in 1997) and we organised shows and developed projects together.

– Abramovic, amongst many others, focuses on the move from object to process and even predicts the disappearance of The Object in art. Post-modernism’s deconstruction and revelation, or ‘un-concealment’ of truths via process, are well worn cultural modes of exploration and expression but we have now moved into the nonlinearity of an information-charged electronic age. How do you feel about this? Culturally, where do you think we (or more specifically, yourself in terms of art) are moving towards?

I would like to think that culturally my art practice is moving towards a more critically astute position from where I can develop exciting and ambitious works which could, potentially, take unexpected forms. Artists have always had to be flexible and now the work force is working in a way similar to the art world. So this means that the art world needs to change – as we’ve always got to be one step ahead! As I work collaboratively with Helen O’Leary (painter from Wexford, based in Pennsylvania and Leitrim) I think I am grounded, to a certain extent. Helen’s interested in crafts, in the local vernacular (making culm balls [homemade pieces of fuel] in Leitrim, crocheting, making jams, etc). The conversations and projects that we develop between us are fun and also, I think, important for me as the tangents I find myself following lead to unexpected and down-to-earth lines of enquiry. I think this PLOT (title for our collaborative project, which we started in 1999) is very complementary to my other work – as I’ve always been involved in multiple projects at any one time, it’s vital that this (local, perhaps parochial?) dialogue with Helen happens. It’s a great way to complement and enrich the hi-tech global travel projects that I also work on. I might have gone off the point here, but what I’m trying to say is that there are always cycles. Things go round. They said that painting was dead and then, recently, there was a painting ‘revival’. We are in a time when the ‘object’ might well disappear, but I don’t think so. There are always people that thrive off doing the opposite of what everyone else is doing. I’ve recently started making objects. My solo show in the Butler Gallery ( A Recent History of What’s Possible . 21 oct-30 nov 2003) included a piece called On Loan which is a collection of works/objects from the Tûp Archive . At a time when we’re being bombarded by flickering images I’ve begun making things again. A primitive return to the fundamental things – and I don’t think that what I’m doing is turning away from the bright, flashy lights of globalism, or the electronic-age. All of that is informing what I’m doing. I’m rendering stuff in a low-tech, hands-on way that discusses the state of things at the moment.

– What do you think about not giving the audience a visually dynamic object that would contains all of the questions, implications and answers but instead, giving them a starting point from which to generate their own process of engagement? For instance, Laboratorio della Vigna operates on a set of clues to a multi-directional/dimensional map rather than functioning on the principle of creating a visual impact.

This was something that myself and Valerie Connor, the Irish commissioner for the Venice Biennale, discussed from the beginning. Val selected me as she was specifically interested in this aspect of my work – the fact that an ‘art bauble’ isn’t necessarily going to be produced as a ‘finished piece’ to dazzle the masses (although it could be! but not in this case). Also, in the context of the Venice Biennale (where artists present their work in a similar way to an art fair – the ‘best-of’ is on display), we were both excited by the possibility to push the dynamics of the event further. Surely there should be more to the largest visual-arts show on earth than merely presenting pretty things to glitter for the people? And as my work was being placed in a venue that is for the local people – a Scuola, confraternity building, I would have been embarrassed to impose something on the locals. That would have seemed degrading.

– What do you think makes the process more valuable than the object for the artist and then for the viewer – perhaps it’s the same for both?

For me, as the artist, the process of working is valuable as not only a way to enter, engage and become part of, the local Venetian community, but also the ongoing process is of great importance. The work developed before the Biennale, continued during the Biennale, and will continue to develop and expand after the Biennale has closed in November. This is a work that is more organic, honest and sincere than, I think, plonking an object in Venice from June – November could be. The location of the Irish pavilion (in a residential part of town) also played an important/vital role in the development of the project. Val and myself are both responsive to site and it is important that there is an integrity to our works. Neither of us would have been comfortable with plonking ready-made work into the laps of the local residents. They have enough to deal with – day-trippers, aqua-alta, tourists, etc.

– How do you think art practice (either your own or in general) is being affected by digitisation, either positively or negatively?

It would be awful if art practice didn’t reflect the larger, global experience. For me, as my work is often unashamedly low-tech, I enjoy exploring aspects of this in a low-fi way. (I’ve made emails and text messages out of plasticine and some were on display in the Butler Gallery).

– There is a sense of serendipity in your art practice and a kind of randomness that is like a stream of consciousness, flowing regardless of the apparent disconnected bits of information. Do you wish for the viewer to assimilate the information with which you present them into their own grid of references or do you intend for them to be conscious of the flow of information without needing to interpret or re-interpret it?

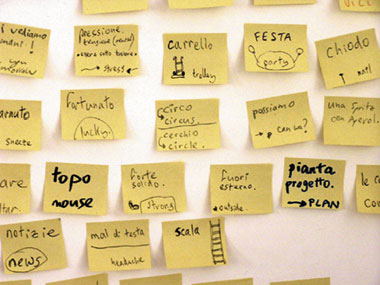

There is an order. Everyone knows about The Butterfly Effect – a butterfly flaps its wings in Thailand and there’s a tidal wave in Europe. Randomness is essential to my work. But so is failure. So is research. The booklets (Papers) in Venice contain disparate material – but there are many ways to connect it all. It’s open – people can join the dots for themselves. I’d hate to ever be didactic or pedantic. The viewer knows just as much, probably even more than I know, so their conclusions could often be more valuable than mine. My work, from the beginning, has been part of a research project. I may go off on tangents, but in a way it’s all connected. I have always been aware that some of my installations can, potentially, be quite difficult for a viewer to enter. Not physically, but mentally. If they’re presented with a pile of clutter and someone else’s hand-scribbled notes, how can they ‘enter’ this conversation? But this has always been a fundamental aspect of the work – the precise fact that today it is virtually impossible to make sense of things. Also, as I’ve mentioned, failure is important. The moment of clarity always appears (for me anyway) on a scrap of paper, rather than on an art surface. I have always striven to be honest – to show the failings, as well as successes, made along the way. The serendipity that surrounds my work reflects how my life is. And my work is very tied-up with my life. My art practice is fluid, organic and flexible, like any good conversation – it follows tangents, back-tracks, bubbles off down a cul-de-sac and touches on many disparate things. But it’s all connected.

– Taking into consideration the shared experiences of people inhabiting any given geo-political location and also the shared experiences of those free to inhabit the global village of dissolving borders, what are your thoughts on national representation as an outmoded model or valid model for cultural diversities and similarities?

National representation has always bugged me. In a situation like the Venice Biennale there has to be method of creating order (although, having participated in it I now realise just how disorganised the entire event is!). Every year people argue that it’s out-of-date, old-fashioned and the national pavilions should be finally ‘destroyed’. But at the moment I think they’ll remain – and of course it’s interesting to see the fluidity that occurs – for example my space (Irish pavilion – although we never called it that, which myself and Val decided was an important thing to do – in a way, we distanced ourselves from the national pavilion thing – if only mentally between ourselves and the people that I worked with), has more Italians in it than Irish. While making preparations, I spent time considering if I should (was it my duty as a collaborative artist representing Ireland?) invite more Irish artists, or artists based in Ireland, to work with me on the project. It soon became obvious, to me anyway, that the way I work is free of barriers/boundaries and I don’t work with people because of where they’re from – but I work with people that I meet or am introduced to. So the project quickly developed as a local/Italian/Venetian project. Then I participated in the Prague Biennale, which had no national pavilions or anything structured like that. But they still insisted on lumping us into

groups. I was in Jacob Fabricius’ group of artists who were referred to as the northern European group. So, although we’re in a global/high-speed communication network (Prague Biennale was very proud that they had artists from LA, New York, Czech Republic, Asia, etc), the old-fashioned ways of sticking together, or categorising people, were still enforced.

– Why did you and Valerie make a conscious decision to distance yourselves from ‘The Irish Pavilion’? Having spent time in Venice and time in your exhibition space I can see that it made sense to collaborate with a network of creative practioneers beyond what are strictly your Irish contemporaries but I don’t understand why you preferred to side-step the idea of being the Irish representative at the biennale.

The entire phenomenon of the national pavilions is problematic, as we know. The Giardini is fine as all the pavilions are there – obvious for all to see – permanent, impressive, grand buildings. But once you leave the Giardini the ‘national pavilions’ are just rooms or temporary premises in buildings used for other functions. It just seemed too invasive to declare that we were turning the scuola into ‘the Irish pavilion’ for 6 months. The locals would think we were off our trolleys – silly foreigners with notions. Although, of course, they probably think that anyway, at least the laboratorio della vigna is not so bombastic and, I hope, a space that belongs to the area, rather than an intruder.

– I would like to understand more about your response to the issue of national identity in Venice. I understand your sensitivities to the local community in the area of the Scuola di San Pasquale and I appreciate your awareness of placement of imposing art works in a community area but at the same time, this is the Venice Biennale where the Venetians are well accustomed to the goings-on of the exhibition. You were chosen to represent Ireland so, do you not feel that by consciously avoiding the association of our national identity you were in some way betraying the honour of being the Irish representative?

I’m very proud to be Irish! It’s where I come from and where my work comes from. Everyone knows that that’s where I’m from. But the (larger) dialogue that my work is part of is coming from artists working in other places. That’s only natural. And it’s not just in the visual arts; I’ve got a friend who’s a writer – his work is part of a European tradition, rather than the Irish tradition. But his work is infused with/comes from his Irish roots/history, etc., you know what I mean?

– Ok, so do you feel a dichotomy of identities between being an Irish artist and being an artist from Ireland?

Yes. I know that being an ‘Irish artist’ is not really something that I would be extremely proud of – I’d never tell anyone that that’s what I am, and I have never referred to myself in that way. There is not an interesting/exciting/dynamic group of ‘Irish artists’ that the art world (I’m talking about the groups of people that I’d be meeting and working with) can conjure up so therefore the notion of ‘Irish artist’ is, I think, old-fashioned. I think what I’m trying to say is that ‘Irish artists’ seem to be parochial. Whereas being an artist from Ireland is what I am. I am an artist. I am from Ireland. I am not an Irish artist, necessarily, as I travel so much. Day 1 of my art career happened when left Ireland – in Berlin in 1997. My work has always been in dialogue with artists working internationally. It’s not just the art world that is flexible/mobile now, but for me I have always felt more affinity with artists like Thomas Hirschhorn, Dieter Roth, Mike Nelson, Gabriel Orozco, Manfred Pernice, Pierre Huyghe, Mark Dion, Olafur Eliasson, Carsten Höller.

– You participated in this year’s Prague Biennale and the central theme was that of the periphery becoming the centre. Geographically here in Ireland, we are hanging on the very edge of Europe but conceptually and creatively we inhabit a very different domain. How do you feel the binary relationship between socio-political, economic and cultural peripheries and centres affect or is affected by current trends in art practice – specifically or in general?

Do you mean – Ireland is on the edge, but creatively we are right in there? I wouldn’t really say that we are conceptually right in there! This ties back to why I wouldn’t call myself an Irish artist. There is still a huge amount of paddy-whackery going on. Artists like Le Brocquy are highly regarded but no one knows who James Coleman is. I bet there are even art students right now who don’t know who James Coleman is. I find this embarrassing. I have, many times, been in the position where I’m asked who are ‘the other Irish artists?’. Depending on my mood the list might contain James Coleman (who people know – the rest on my list are unknown to whoever’s asking me. And this is always someone working in the international visual arts), Dorothy Cross, Alice Maher, Willie Doherty, Kathy Prendergast. Of course, a lot of this centre-periphery thing is all about fashion. Eastern Europe is very fashionable at the moment. On the cusp of entering Europe, but still an outsider. Albania, Czech Republic, Latvia. Also, the real-estate is cheap – and I’ve heard that this is why some of these Biennale people go over there. But we’re not meant to talk about that. Related to this is the thought that perhaps art practice moulds itself around the art world (centres AND peripheries), rather than vice versa.

This interview was conducted in a series of e-mailed conversations between Regina Gleeson and Katie Holten in Autumn, 2003. Gleeson discusses Holten’s work further in an article in CIRCA 108, summer 2004.

Regina Gleeson