|

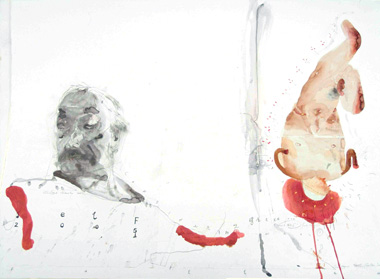

| Patrick Graham: Self-portrait, mixed media on board, 75 x 112 cm; courtesy Hillsboro Fine Art |

The first show of Paddy Graham I saw was in Cork. Despite its title, The Lark in the Morning, I had never seen work so honest and smelly and revealing. I felt it gave me the license to take my guts out and say, "See, my guts, wanna have a look, take it home with you?" He then painted on the back of canvas. I think he wanted to say, "This is the real me, curtains down, I am not putting up a front anymore."

Eleven years on in his life he shows Collateral Series in Hillsboro Fine Art in Dublin. He no longer paints on the back of torn up canvas. There are no canvases- this is a display of drawings, collaged together out of scratchy sketches. He had shown this kind of drawing before, in the Green on Red Gallery, the RHA, the Civic Theatre, the Jack Rutberg Gallery in LA. This work looks like it has been stitched together after a high number of long nights filled with vivid dreams. It is as if he had been sleeping with pen and paper beside him, scribbling and jotting things down in the dark after every dream that woke him, and then the next day trying to make sense of it all by putting the jigsaw together. The genitalia were always in his work and hats off to the gallery owner John Daly for putting the most explicit and possibly offensive drawings into the window for every passer-by to see. Not everyone will feel encouraged to go inside, after being confronted with near-uncensored freedom.

|

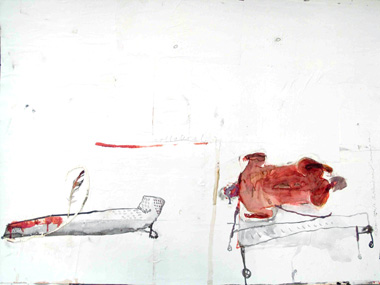

| Patrick Graham: from Collateral series, mixed media on board, 75 x 112 cm; courtesy Hillsboro Fine Art |

The figures, or models, as he entitled some, have become rawer, less delicate, less carefully executed, less Schiele. Like a song you have sung as a child and you are still singing it as an adult, but without the sweet, illiterate, searching voice. Something else has changed: the urgency of a Mohamed Ali, leaning so far backward into the ropes away from Joe Frazier’s punches, that it makes you think he is never coming back, is gone. Or at least, Frazier doesn’t hit as hard anymore. Life doesn’t. And hell is no longer other people. The urgency and desire that is left comes from the medium itself and its temptations. Graham is still trying to ‘stick it up to them’. One wonders if he still has to. How many insides of spread legs and dangling penis can you look at without wondering what the heck they are for? Does everything there is have to be either male or female?

Few boat-like vessels have remained in his work and how they stand out from the lying-down, tortured, sleeping, dying, masturbating, sometimes plump red bodies. This is where Graham, the poet, leaves his mark, in the ghost ships on dry land, gray and Irish, starving of water, melancholic and unable to speak. The urgent, furious, yet gentle and fertile Graham shines through once more, giving us the confirmation that he still wants to show us art which doesn’t live today and die tomorrow, art which will have a special place in Irish art history. For, no-one here paints like this. No-one here has ever shown pain personified, in the stillness and silence of a lost ship. Perhaps today this ship has an anchor, a port it can go to. But it is still gray and distinctly Irish. It keeps coming back to haunt us.

Thomas Brezing is an artist based in Co.Dublin.