Otobong Nkanga, The Breath From Fertile Grounds

Temple Bar Gallery + Studios, 8 December 2017 – 10 February 2018

Otobong Nkanga has developed a distinct practice that is both intuitive and inherently research-based. The Breath From Fertile Grounds, the Nigerian-born artist’s first solo show in Ireland guest-curated by Caroline Hancock, arises from work carried out and conversations that took place while on a visit to Dublin during which she delved into areas of interest relating to language and literature as well as nearby natural and built environments. On arriving at the exhibition, I sat on the gallery’s window-lined bench to read novelist Gavin Corbett’s ‘Bog Metropolis’, a commissioned text written in response to the show. From time to time, my gaze left the page to look up again at Nkanga’s mysterious wall drawing, struck each time by a different effect in relation to Corbett’s piece. Almost entirely visible from the street, the exhibition intrigues and draws viewers in from the busy Temple Bar Square outside but it can also feel intimidating in its sparsity. Any viewer that gives Nkanga’s work time however is amply rewarded as it reveals a complex strata of interlinked ideas that take root and quickly germinate, growing in directions both familiar and unforeseen. Tuning into the elements that have either been created for the exhibition or brought into the space, the difficult relationship between rural and man-made environments is borne out, shaped as it is in large part, if not by dependency, then by exploitation.

The constituent parts that make up this exhibition are delicately connected by line, colour, material or form. Instinctively I look at the show from left to right, as though reading a passage of text in a book. On the left-hand side of the room, the two walls are painted in four shades of mint green. In the first section closest to the window, on the wall perpendicular to the street, a black wrought iron bar protrudes down toward the floor and then twists across, running horizontally towards the back of the gallery, over which hangs a length of white cotton. On this raw canvas is a two-verse poem by Irish writer Doireann Ní Ghríofa, printed in English on the left and in Irish on the right. By inviting Ní Ghríofa’s voice in her two native languages into the space, Nkanga manifests a multiplicity of perspectives, thereby subverting a still prevalent albeit outmoded patriarchal narrative structure that so often excludes more than it lays bare.

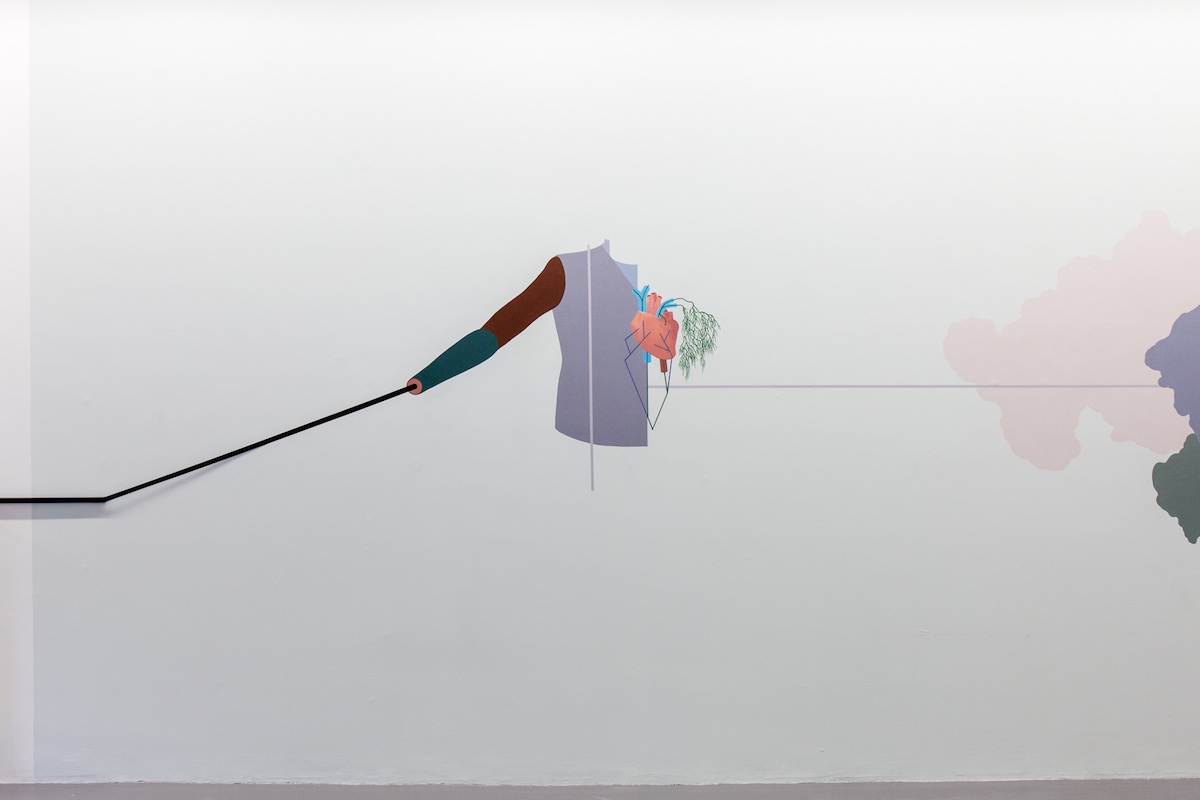

Ní Ghríofa’s poem suggests the black rod over which the cotton is draped is an abstracted gate or boundary, a possible source of tension. The placement of the English and Irish language versions of the poem adjacent to each other also speaks to the biformity that underlies every lived aspect of our postcolonial culture. From there a masterly stroke of trompe l’œil initially only barely registers: where the iron rod ends it meets a short length of black elastic which continues a thick line up at a diagonal until at some indiscernible point it blends into another, this time painted directly onto the wall’s surface. These slippages from the three to two dimensional and back again bring a level of surreality to Nkanga’s work only reinforced by her metonymic depictions of the human figure, like those leggy creatures that stand across from each other in The Weight of Scars (2015), Nkanga’s startling tapestry that featured in 2016 at EVA International in Limerick, where this artist’s work was first introduced to Irish audiences. Appearing here is another cleaved form, a single-armed mauve torso abutting a heart from which emerges a sickly shrub, the heart painted onto the surface of the body reminiscent of those overly-familiar depictions of an immaculate mary gesturing toward a pierced and sacred heart sitting unnaturally atop her chest. In contrast to this first figure which, with arm outstretched, evokes a kind of longing, the second human frame here, on the back wall, with a cord wrapped around its elbow and clenched in fist, signals at pressure and constraint.

A pale thin painted line brings the first partial trunk into contact with four masses of colour, continent-like in appearance, that converge in this corner of the room. They take the wall drawing to the back of the gallery where a blot of black paint bleeds into the soggy soil packed densely into a transparent container that juts out from the wall, bearing the weight of the plants growing inside. In placing this unmarked map of sorts alongside the material of which all land is composed, Nkanga upends our calibrated perception of scale and upsets an understood balance of power. “Everything we have, own or possess”, Nkanga says, “derives from the earth, even though it might have been transformed by artificial means… we cannot disassociate ourselves from nature.”[1] As modest as the act of bringing soil into the gallery may seem, the sentiment that motivates it is far from slight. Instead it brings attention to the reality hidden in plain sight – a common disregard for, despite our complete reliance on, the muck earth beneath every smooth concrete floor.

It occurs to me while reading of Nkanga’s earlier work, which includes an Allan Kaprow inspired piece called Baggage (1972 – 2007/08), that, like much of the American artist’s work, no material remains of The Breath From Fertile Grounds will last beyond the exhibition itself: the wall drawing will be painted over and the plants, the gallery invigilators tell me, will be returned to their natural habitats. This site specific exhibition does not coincide with the creation of a permanent artwork, nor was that ever its aim; instead it seeks, in the subtlest of ways, to activate space by inviting the viewer to consider the improbable role played by nature in its make-up. To this end, a small, lichen-topped rock is carefully situated in the middle of another black bar that links the gallery’s two permanent concrete struts. Raised up, and in such a prominent position, the significance of the rock’s materiality is thrown into sharp focus, its unlikely might on proud display. Moreover, each of the structural struts is reinforced by small measures of Georgian brickwork, installed perhaps to make succinct the intimate relationship between nature and industry. “Materials never leave this world”, Maggie Nelson writes in her book The Argonauts, “They just keep recycling, recombining.”[2]

In the corner of the gallery opposite its street entrance I stood beside a family – a mother and her two children – as they too considered a series of objects gathered there. Another wrought iron bar, like that featured on the other side of the gallery, protruded from this wall, once again bearing the weight of sheets of cotton adorned with text, this time by Nkanga herself. Reading the first page together, we noticed there were other layers behind this sheet and so held each length up one by one so we could read the passages underneath. I was surprised by the tiers of text lying behind the first so inconspicuously and conscious that I might have missed them had I passed by on my own. Before I left the exhibition the invigilators explained that Nkanga had worked in the gallery solidly morning till night over one weekend to complete the wall drawing. Working without a plan she would take breaks and speak to whoever was passing by. Likewise, her powerful exhibition acts as a site as much for reflection as exchange through which there is purposefully no single or prescribed route.