Circa continues to be delighted with our expanding collaborative project titled Travelling South, In Theory, supported by the magazine’s ‘Archive Project Editor’ award to Dr. Brian Curtin in 2022. This project commissions writers in South and Southeast Asia to engage with Circa’s archive. Below he briefly introduces Nurul Kaiyisah’s commissioned essay. More details on the project are here.

*

Dear Brian, Dear Circa is a speculative and evocative text that responds to the original brief’s intimations of vastness, between regions and eras. Nurul takes a cue from essays already published for this project – Carlos Quijon Jr.’s concern with what he named “errant affinities” and Thái Hà’s epistolary form. Both aimed to counter limitations in traditional comparative scholarship, allowing for a rethinking of the conventions of scholarly engagement. Nurul similarly turns the invite of Travelling South inside out as a means of thinking through its epic quality: to wonder about the efficacy of available tools for building connections, to pose questions, propose interpretation as a problem, and speculate relationships rather than assume them.

The epistolary here is, as the author writes, apposite and fecund. Private ruminations are made public for others to judge and run with. And, acutely, there is a sensing of connections or relationships that “speak” to what distinguishes this article: a focus on what Nurul calls “femme-identified thinkers and doers in art worlds” or what we can ordinarily identify as feminist. Frustration and comparable sentiments such as irritation are the embodied responses for those of us who work within and against the prevalent discourses of art history, theory, and criticism. And this, of course, includes responses to male-centric commentaries. We are not mere disaffected witnesses because vexation is a condition of oppositional, tangible, action.

Brian Curtin

Bangkok, February 2025

This is not the article I promised to write. It is a letter explaining why an article isn’t possible right now.1

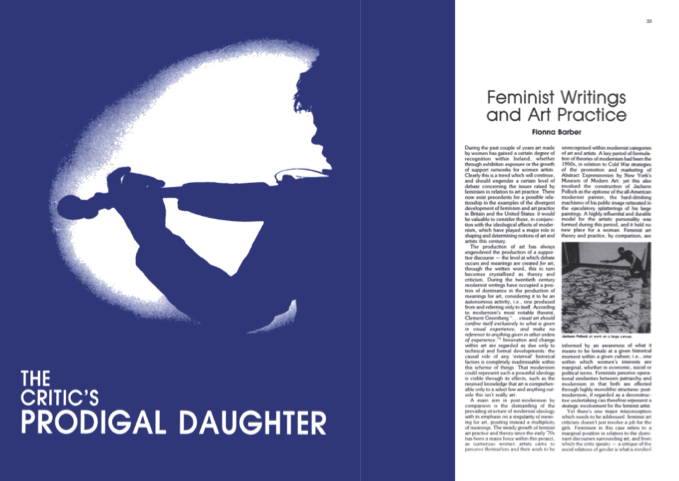

Brian – if I may – I found myself, oddly, in a similar position to Irish feminist filmmaker Pat Murphy when I was approached to write for Travelling South, In Theory. In 1987, Murphy wrote an open letter to Circa, in her exasperation about the governing body that had disbanded the Irish Film Board. Like Murphy, I too was tasked to posit my retrospection of theories that “contained real issues”3 – ones that demonstrate the latent possibilities of connection between 1980s Ireland to a region I call home, Southeast Asia. Strangely, the form of this open letter struck a chord, intimating a kind of connection between her and I, despite the temporal and spatial distance that spans between us. At once, I recalled a similar open letter that Indonesian artist Mia Bustam (1920–2011) had written for her contemporary, Kartika Affandi (1934—), where the curator and scholar Brigitta Isabella had analysed the epistolary as an imperative feminist genre. Brigitta deftly writes: “Here we read and re-read the historical letter from our feminist mothers in order to continue their moving correspondence…”.2 The format of the epistolary feels apposite here, so fecund in what and how it proffers ideas and especially so in housing my rudimentary efforts to gather femme-identified thinkers and doers in art worlds from seemingly incommensurable spatial-temporal dimensions. Perhaps this ligature I observed between Pat, Mia and Brigitta is embryonic of the “errant affinities” Carlos Quijon Jr. speaks about, as part of your – Brian’s – project.3

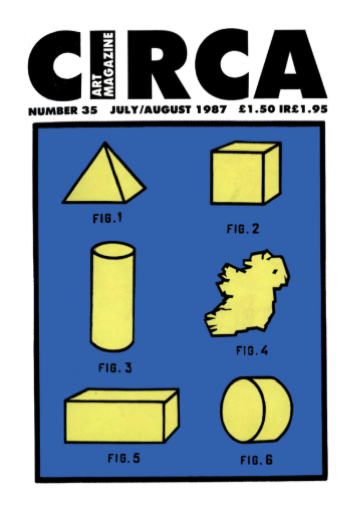

CIRCA #35 that featured Pat Murphy’s open letter

CIRCA #35 that featured Pat Murphy’s open letter

Similar to Carlos’ exploration of Irish and Southeast Asian historical correspondence, my letter here embraces this spirited venturing for unusual juxtapositions, atypical pairings that are inherent in Carlos’ search for “errant affinities” to emerge and thrive between these regions, cultures and more importantly, temporalities. For Carlos, these traces of co-presence could be observed from the operations of “transpacific” and “sinophone”. In my letter, on the other hand, I hope to locate sites of “disobedience” and solidarity within the virtual nooks and crannies of the Circa archive – particularly, ones that speak to feminist praxis in documenting artistic practices. These sites embody my attempts in constellating between the regions of Ireland and Southeast Asia. Here, I seek refuge in the “Southern praxis”4 that is steadfast in epistemological revisions and resists against singularity of knowledge production and systems. The underpinning to these “errant affinities” that I demonstrate in this letter is inspired by the spirit of solidarity and enacting “epistemic disobedience” within the scholarship on the Global South. Strategies of decoloniality that encourage an epistemic de-linking, as Walter Mignolo proposed, premised my endeavour to outline an assemblage of artists, art writers and art writing that spans between theory and practice, between vast expanses of regionality, between Circa and academic journals of today.5 Indeed in the first decade of Circa’s publishing, art writers and feminist art historians alike turned to the epicenters of Western art historical knowledge then – Britain and America – to approach the task of documenting the practices of Irish women artists. Writers such as Lucy Lippard, Roszika Parker and Griselda Pollock and their subsequent publications were often cited by writers featured in the magazine when presenting possible routes to addressing a lacuna in art writing and scholarship.6 In this letter then, I will shift the locus of the discussion on feminist methods to documenting women artists’ practices to beyond the geographies of Euro-America – one that speaks directly to aforementioned “errant affinities.”

CIRCA #40 that featured one of Fionna Barber’s writings

I propose a suspended moment, a temporary site, within this open-letter – much like Brigitta had observed in Mia’s letter to Kartika – where boundaries are porous and the flux of time and space is embraced. My letter here offers a space to gather art writings in proximity to one another, convening art writers from 1980s Ireland and contemporary Southeast Asia in their discussion of women artists. From my vantage point as a researcher in the digital age, I observe discussions of modes and strategies to read the praxis of women artists that leapt beyond the pages of Circa and felt like attempts to converse in solidarity with feminist art historians, writers and researchers in current-day Southeast Asia. With this desire in mind, this letter certainly requires a deferral of scholarly conventions, for me to materialise this space within text. How else could I invoke these brilliant thinkers and doers across Ireland and Southeast Asia through chanting the names of their fathers? Kartika would be referred to as Kartika, lest her spirit be appositely conjured in this ritual. Allow these subsequent words offer you the lay of the land then, Brian.

This unlikely assemblage of art writings from the two regions residing within the space of my open letter is where the decolonial spirit of the South-South comes alive, I feel. Art historian Joan Kee’s sentiments on exploring the connective nodes in Afro-Asian solidarity beyond orthodox comparativist frameworks, is resonant here in my constellative thinking on the regions of Ireland and Southeast Asia. Artfully, Joan writes: “To understand the world only through forward linear and received geographies betrays a smallness of vision…”.7 Thus, in “opening geographies and spheres of decolonial thinking and doing”, I attempt to exercise “disobedience” by proffering a space in my open-letter to witness these interactions between art writers from 1980s Ireland and contemporary Southeast Asia.8 Conversing regarding the all-too-familiar feminist task of documenting the praxis of women artists, these writers and writings were symbiotic in pursuing plausible modes to address the assignment at hand. My letter merely carves a site for them to convene. Furthermore, the proposed assemblage of art writings and art writers is premised by a primary line of inquiry: How do we document and write on the praxis of women artists contingently to their oeuvre of works? The historiographical task of narrating the histories of women artists rest heavily on the shoulders of art writers and cultural practitioners from particular spatial-temporal dimensions – the pages of Circa and also, contemporary academic writings produced within Southeast Asia.

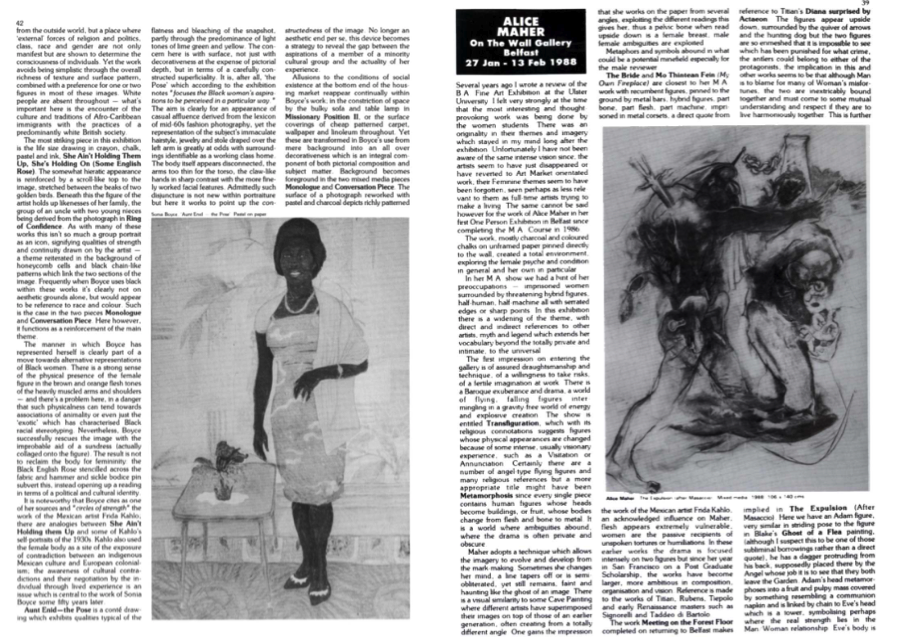

If you would allow me to confabulate, Brian, I could image the art historian Yvonne Low prompting these dialogues with the Irish art writers of the 1980s, from a reminder that the project of “recovering” histories would not simply suffice, in documenting the praxis of women artists. As she posits, the approach in mining for “compensatory” narratives could only serve to regard these women artists in silos from their contexts and artistic ecologies they were deeply embedded in.9 Akin to a response of sorts, I draw on the writings of scholar Fionna Barber and artist Jack Pakenham as they reviewed the exhibitions of artists Sonia Boyce and Alice Maher respectively, within the pages of Circa. Both writers had intimated a close reading of the artists’ visual language, particularly to the developments in their artistic trajectories on canvas. From the close attention to the vocabulary of an artist’s aesthetic, Fionna and Jack had also enabled multiple entry points for others to read the works of both artists. In reviewing Sonia’s works, Fionna proposed a feminist re-reading of the exhibition revolving around the “constructed” representation of the Black women, from Sonia’s approach of utilising the colour black for multiple purposes.10 Similarly, Jack had also highlighted that apart from the overt, rich resource of symbolism evident in Alice’s works, the distinct composition in her works was notable in the aesthetic experience of the exhibition. He suggested, in his review, to read her works from “several angles” that Alice has worked on and also to pay close attention to mark-making and lines that signposted her creative process, so as to embark on fresh re-readings of the oeuvre displayed.11 Do these methods not propose an intriguing response to Yvonne’s call, Brian? In their efforts towards documenting artistic praxis in the writing of art history and art criticism, Fionna and Jack focused on foregrounding the visual vocabulary of these artists for the readers of Circa and thus, encouraged the latter to generate a plurality of readings of their own. This then situates these artists within an ecology of production, reception, and circulation of their works, drawing the tangible connections between an artist and her audience.

In addressing the possible historiographical methods of writing on women artists, the position of the art writer itself was also highlighted in the writing of these narratives. From the pages of Circa, writer Claire Hackett and artist Rose Anne McGreevy highlighted that individuals who hold the pen for documenting histories of women artists should also examine their own positionalities.12 Here, the politics of visibility for women artists and their representation are discussed within these speculative conversations between art writers from Ireland and Southeast Asia – with a greater focus on the narrators and curators of stories from both temporal-spatial contexts. The moving image scholar and curator May Adadol Ingawanij might offer a timely interjection here, with her contribution about observing cultural practitioners and artists who “thought counter-intuitively about invisibility”.13 To what extent can the art writer, from her position, extrapolate on the lacuna of women in art histories through productive means? Indeed, an exhibition review from Irish artist Anne Carlisle offers a demonstration of May’s proposition to look beyond the surface-level optics of representation. Grounded in the spirit of Griselda’s “feminist interventions” within art history, I believe Anne intended to exercise agency within her role as an art writer and intervene in artist Vivienne Burnside’s representation of femme-figures. Despite Vivienne’s attempt to engage the femme body as subject, Anne was quick to parse that the artist was certainly employing a masculinist visual language in depicting this subject matter: from the figures’ faceless expressions and submissive body gestures to considering the prescribed male viewer of these works.14

It is at this juncture that I hear the voice of art historian Flaudette May V. Datuin as she concurs with Anne’s attempt to unravel these representations, from the agency embedded in art criticism – for Flaudette herself had written on the analytical categories young art writers could adopt in ensuing the rigour of art criticism and documentation of praxis is maintained.15 The criticality within an art writer is emphasized, through both Anne and Flaudette, as her duty, here, is double-barreled. It is not merely critiquing but also being cognizant of the complex matrix of “identity, agency and structure” underlying the optics of representation – so as to offer these writings as productive contributions to the intertext of art history.16 Thus, Anne and Flaudette converse on similar tangents with regards to the role of the art writer within the machinations of knowledge production in art history.

As these art writers from the spatial-temporal contexts of Ireland and Southeast Asia confer in my letter, I also imagine the sentiments of frustration arising as well. In their shared solidarity and “epistemic disobedience,” these dialogues are meant to upset conventions of art historiography. I detect here, amidst my perusal of the Circa archives, that several articles mention moments of irritation experienced by male-centric audiences towards works produced by women artists. Artists such as Phil Nalty, Debi O’Hehir, Cristina Rubalcava and Dorothy Cross were all described as having a visual vocabulary in their works that “frustrates… the male viewing pleasure.”17 Furthermore, Circa also featured anecdotes of these overt responses by men recounted by women artists themselves. Irish artist Catherine McWilliams had revealed in a conversation with Circa that in receiving “silly remarks” by these men, she wondered: “After all men paint female nudes all the time and no one sees anything strange or unusual about it.”18

Notwithstanding the discussion on whether their art is considered feminist in nature, I would like to draw your attention here, Brian, to the embodied irksome feeling that is underlined in these articles as a mode for writing women artists’ narratives as well. Curator Joleen Loh, who writes in contemporary Southeast Asia, had also underlined that in her attempts to chart the trajectory of artist Kim Lim, “art historical tools used to track artistic lineage…become vexed.”19 In each instance where the bubbles of indignation simmer over the pages of Circa, I find that what lies in its subtext is far more imperative: the conventions of seeing, reading and documenting artistic practices will only be able to placate the male virtuoso and his familiar, masculine visual languages. Any resistance to these orthodox forms of artistic expressions or historiographical modes would be met with dissatisfaction.

In turn, would it be possible then to inverse this sense of vexation to one that might indicate the parameters of the discipline that ought to be revised and made porous? Certainly, the frustration among artists and art writers as they grapple with the task of engendering a multiplicity of praxis, simmers. The episode I imagine Joleen discussing with Catherine asserts that this dissatisfaction with canonical ways of seeing affects at every level of artistic production, reception and circulation. Retrospectively, these encounters with the borders of the discipline could be refashioned and channeled to productive means as well. The affliction embedded within the master’s tools, in the words of Audre Lorde, must be felt to understand how to dismantle the house. It is through these vexed sensations wherein one could begin tracing other sites of epistemic disobedience as well.

Brian, I hope you too were able to observe this constellation of art writings and personae and their interactions with one another, as I have. After all, my open letter could only entail so much, as I could only conjure, in Donna Haraway’s words, “the view from a body”.20 This site that gathers this assemblage and simultaneously allows us to witness lively discussions from seemingly incommensurate contexts is merely an embodied proposal of my open letter. An article is not possible right now, for this experiment to offer a space in charting these “errant affinities” still awaits its jury – whomever and wherever they might be.

Yang tidak lupa,21

Kai

The editor and author would like to thank Roger Nelson for his informal support with this article.