|

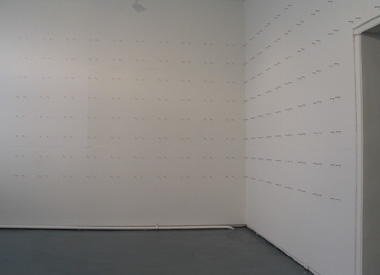

| Margaret O’Brien: My room, 2004, installation shot; courtesy the author |

Margaret O’Brien has recently completed a two-year MA at the Slade School of Art in London. A printmaker by training, over that relatively short period of time her work has changed from large-scale screenprints on aluminium to the work on show today.

|

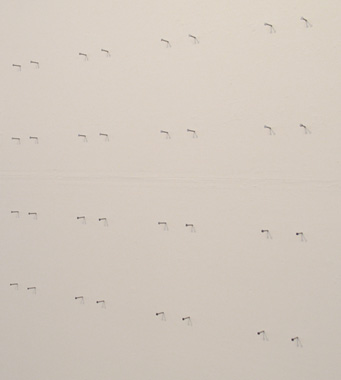

| Margaret O’Brien: My room (detail), 2004, installation shot; courtesy the author |

There are two main spaces in the gallery. In the first, O’Brien has, at first appearances, left the space almost completely empty. After a few moments you realise that there are a series of nails hammered into the walls. Spreading out from one corner of the room, the nails are arranged in a grid, hung in pairs, and look as if an installation of small paintings has been removed, leaving only an impression of what was or might have been. This grid, entitled My room, spreads across two walls, and forces a consideration of the rest of the space. On the opposite wall, the windows have curtains stretched over frames made to the shape of the windows – they at first look like translucent canvases, and overwhelm the delicacy of the nails. Realising that these canvas-curtains are not a part of the work, you return back to the space, and into the next room to Untitled, where a loud rasp of white noise draws you in.

|

| Margaret O’Brien: Untitled (detail), 2004, installation shot; courtesy the author |

Through the open door of Room 2 the darkness is lit up by flashing lights and a cacophony of grinding white noises, popping and buzzing across the space. A few feet inside the door, at head height, is a line of suspended fluorescent tubes, occasionally blinking on and off. In no apparent order, other tubes are arranged around the space, some left lying on the ground, some stood on one end in corners. It becomes apparent, through the buzz-saw fuzz of white noise, that the lights have microphones attached and are connected to an amplifier system, spread across the gallery. The lights have had their spark-charger adjusted, so that they never quite fully light up. They are in a constant state of gathering enough electricity to charge the light. The noise is the sound of the electricity surging to start the light. The act becomes a spectacle: a vicious circle of tubes trying to power themselves – you watch to try and discern a pattern or some sort of order to the apparent chaos, but none comes. You assume that either you have not found the code or that in fact there is none.

|

| Margaret O’Brien: Untitled (detail), 2004, installation shot; courtesy the author |

Back out by reception, out of the concentrated zone of white walls, is a final piece, Say nothing and keep saying it, a video projected in a broom cupboard under the stairs. The cupboard door has been left slight ajar, and the tiny projection is displayed under a fuse box, almost on the ground. It is a piece that you cannot ‘square up’ to and take your time to watch – the sheer physicality of the space makes it impossible to do so. The video shows the inside of a letterbox. It is closed and the video appears silent. Eventually the letterbox opens and white light bleeds in with a rush of voices, all muttering over each other. It is only from the title of the piece that you guess they must be saying ‘say nothing and keep saying it’. The letterbox closes, and the voices disappear. You wait for a bit longer, to see how long it will take for it to open again. But here, as with trying to find a pattern with the lights, you are defeated. The video is not on a straightforward loop, and the frequency with which the letterbox opens and the duration of it being open varies.

O’Brien’s work carefully considers what we perceive of as comfortable gallery spaces and what we expect from an artwork. She successfully sets about breaking the narrative of continuity within a work of art, and any easy reading of it. However, humour is not lost on O’Brien; say nothing and keep saying it is a particularly Irish reference, and she is fully aware of her attempts to frustrate the viewer. This humour, combined with a minimalist aesthetic, shares ground similar to artists such as Ceal Floyer. O’Brien, however, describes her work in terms of psychological spaces and emotive distance, and within this friction between emotive and aesthetic space she shares territory with another ’emotive minimalist’, Eva Hesse.

Paul McAree is an Irish artist based in London and is Director of Colony Gallery in Birmingham.