Ths article is the introduction to the forthcoming book, Space: Architecture for Art, edited by Gemma Tipton and published by CIRCA.

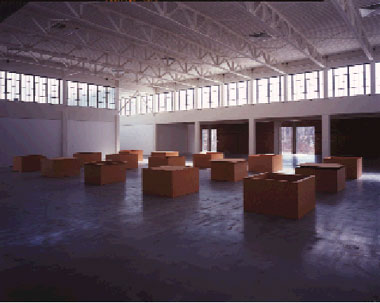

“Guys in suits who can’t paint [1]," a remark made by Frank Stella, neatly encapsulates the feelings of many artists about the architects who design the buildings in which they show their work, and in which it is collected. In Stella’s case, his dissatisfaction led him, as it did with Donald Judd, to explore architectural designs for museums himself. Judd’s conclusion was the Chinati Foundation at Marfa, Texas, a conversion of a disused army barracks in the Chihuahua Desert. Stella’s took him in a different direction. “There are millions of square feet of warehouses available for contemporary art where it looks better than in a neutral box, so we need new forms." [2]

Stella is an admirer of Frank Gehry, architectural master of these ‘new forms’, and Gehry acknowledges the influence of Stella and other artists, such as Claes Oldenburg and Coosje van Bruggen in his work. But under which other influences does the architecture of contemporary art museums fall? From where does today’s concept of the art museum derive, and how has its traditions shaped spaces as diverse as Santiago Calatrava’s Milwaukee Museum extension (1994-2000), Yoshio Tanuguchi’s MoMA extension project (opened November 2004), or Herzog and de Meuron’s Tate Modern conversion (1994-2000) – three widely different museum projects, but all ostensibly built for the same purpose?

Despite this variety, this experimentation, there is still dissatisfaction. “Where are the museums that match my work?" asks Katharina Fritsch in an essay to accompany her 1995 exhibition at the German Pavilion of the Venice Biennale. [3] But as art continues to do its job (at least part of which is to constantly redefine itself, reinventing and breaking its own boundaries), how can a museum be made that will match the work of painters, sculptors, performance artists, those with digital visions, situationists, dadaists, futurists, modernists, postmodernists and all their artistic allies and antagonists? And how can a single concept of the ideal museum cater to institutions whose brief is simultaneously to collect, archive, display, commission, surprise, delight, educate – and (these days) act as catalysts for the cultural and economic regeneration of the areas in which they find themselves sited?

While this introduction mainly deals with larger spaces, the architectural issues of space that are raised hold equally true in smaller galleries. Indeed, within smaller spaces, the issues are often intensified. [4] The gallery can be one of the most exciting and creative of architectural spaces, its brief generally more open and receptive to innovation, and yet architects equally find themselves having to contend with the weight of historical baggage attached to the idea of a museum, the inherited architectures and experiences of place. When the Mona Lisa was stolen in 1911, in a clear example of the pulling power that presence of absence can exert, thousands of people queued at the Louvre to see the empty space the painting had left behind. In Stealing the Mona Lisa, Darian Leader takes this as his starting point to discuss what we are actually looking at when we are looking at art. Art, he concludes, creates a caesura [5] through which the viewer can briefly perceive the larger absence, beyond which one can come to enlightenment, transcendence, God – whatever it is you think you’re looking for when you go to a gallery or museum. [6] But the physical context of the Mona Lisa ‘s theft, left largely undiscussed by Leader, is just as worthy of analysis as the particular piece that was stolen. The Mona Lisa ‘s larger frame, the Louvre itself, was the first public art museum, the first treasure house for the masses, the first space to take art out of its context, elevate it to the officially state-sanctioned status of art object, and re-present it to the public as part of a new narrative history of what art is. [7] It is interesting, therefore, that this was the space from which Peruggia, the thief, decided to liberate his prize (he later claimed it was an impulse crime, committed ‘on spec’). So what caesura do museums create? And what kind of space, or absence do they create for our perceptions?

It is this container, the Louvre and others which followed it, including the British Museum in London (1823-47, architect Robert Smirke) and the Altes Museum in Berlin (1824-30, architect Karl Friedrich Schinkel), which have given us our paradigms for the display of art. Drawn originally from the ‘galleries’ connecting apartments and offices in grand buildings such as the Louvre, Vatican and Uffizi, and decoratively hung with portraits and paintings, these new museum galleries modelled themselves on their predecessors – either by taking over their premises, or aping their design. These elements of architectural design include impressive entrances, central gathering spaces, ceremonial staircases (signifying ascension to knowledge), and enfilades of regularly-sized and shaped galleries, with prescribed circulation routes. The Enlightenment supplied the didactic impulse of museums, and structured the philosophical aspirations of the model which takes the viewer on a prescribed, generally chronological route through art and cultural history. These paradigms, with only a few exceptions, remained largely unchallenged until the end of the last century and the beginning of this one.

Added to the mix, with the temple-like façade of the Altes Museum (for example), was an element of secular religiosity, an element which continued internally with recontextualised works of plundered ecclesiastical art. That the contemporary art museum is a secular temple, a cathedral-for-our-time, is therefore a cliché almost 200 years old, and yet one continually dusted off and presented with a polish as if something brand new had just been discovered. Yet the history of the museum is relatively brief. Given that the Louvre was only opened to the public on 10 August 1793, it would be wrong to imbue our idea of the art museum with a sense of unalterable timelessness. The late-eighteenth-century Louvre, like its British and German sisters, though it began life as a product of the revolution [8], developed as a space for colonization of the past as well as a repository for the fruits of imperialism and colonialism themselves. [9]

For the next hundred years, the display of paintings still resembled the Wunderkammer concept – that of the cabinet of treasures, where every available inch of wall space was crammed from floor to ceiling with paintings of every size and shape. Contemporary paintings of the Louvre and the Paris Salons, such as Samuel F.B. Morse’s Exhibition Gallery at the Louvre (1832-33), illustrate this kind of hang. In 1845, Charles Eastlake (who was to be made Director of the National Gallery in London in 1855) advised his trustees that “it is not desirable to cover every blank space at any height merely for the sake of clothing the walls and without reference to the size and quality of the picture." But it still wasn’t until 1887 that the ‘single’ line’ hang was achieved at the National. [10]

Brian O’Doherty develops a persuasive case for the inevitability of this development in his influential series of essays for Artforum (written between 1976 and 1986) [11], where he discusses how Impressionism broke and remade existing perceptual laws and created pictures which seemed to escape from their frames, and so demanded their own discrete conditions of viewing. It was this period, he argues, which also blurred, and then broke, the boundaries between picture and wall. This led ultimately to installation art, and art where the gallery wall became part of, and sometimes subject of, the image.

With this development, the history of art becomes inextricably linked with the history of museum architecture, and of curation and museology. “Hanging," says O’Doherty, “editorialises on matters of interpretation and value, and is unconsciously influenced by taste and fashion." [12] And inevitably the spaces in which art is hung come to shape and dictate a considerable portion of that taste. One of the first architectural articulations of the debate which was going to continue to hover around the building of exhibition spaces for art took place at the end of the nineteenth century in Vienna. The Ringstraße project there aimed to gather all the major cultural and institutional buildings of the Hapsburg Empire around the curve of a newly created boulevard in what had been Vienna’s ‘green belt’. Each building was to have its own historical style. Completed in 1891, the Kunsthistoriches Museum (architects Gottfried Semper and Karl von Hasenauer) created a massive building in the style of the Italian Renaissance. The enormous entrance hall of the Museum, with its monumental marble staircases, leaves you in no doubt of the historical weight and cultural significance of the works you are about to see. From 1890 to 1891 Gustav Klimt and his company of artists (the Künstlercompagnie ) were commissioned to create a series of allegorical panels for the main hall of the Kunsthistoriches, spanning the history of art from ancient Egypt to Cinquecento Florence.

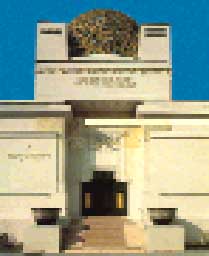

In 1897, only six years after completing this project, Klimt was involved with the creation of a totally different way to experience art, with his selection as the first president of the new Association of Austrian Visual Artists Vienna Secession . The aims of the Vienna Secession were to find a totally new form of expression in art, rejecting the traditions of eclectic historicism embodied in the art of the time, and by the Ringstraße architectural project in particular.

The erection of its own building was one of the key projects of the Vienna Secession, and was discussed in the inaugural meeting of the society. Joseph Maria Olbrich was commissioned to design the building, and a site had been found on the Ringstraße itself. But when Olbrich’s designs were unveiled in the Autumn of 1897, they were violently rejected by the Municipal Council and had to be transferred to the less prestigious Friedrichstraße. The Secession building (1898) is one of the key works of the Viennese Art Nouveau style. It and the Kunsthistoriches Museum embody the dialectic between eclectic historicism and modern architecture. The pure clean forms and unbroken planes of the Secession’s interior galleries point towards O’Doherty’s ‘White Cube’ [13], and while the Art Noveau style still called for mythical forms (such as a crown of gilt laurel leaves, and topless dancing maidens in a frieze around the exterior), the clean functionalism of the interior, its glazed roof, with a second internal glazed ceiling, bathing the main exhibition space in diffused light, and the flexibility and adaptability of the main space, make it a revolutionary prototype for contemporary art spaces today.

The Vienna Secession believed in the concept of the Gesamtkunstwerk, the ‘total work of art’, where architecture, interior decoration and lighting combined to create the space in which a work should be exhibited and ‘read’. That the space they commissioned for this project should be the precursor of what we would now call a ‘neutral’ space (the clean white box), forms an articulate part of the argument that there is really no such thing as a space which does not affect what it contains in some way, even if that space is a white cube.

Two further developments must be recognised in the transition from the Louvre / British Museum model of the museum to the contemporary art museum as we understand it today. The first of these was the entry of the United States into the world art market. Initially copying European models, new American museums, such as New York’s Metropolitan Museum of Art (from 1880, initial architects: Theodore Weston 1880, and Richard Morris Hunt 1894) were driven by the desire to demonstrate great wealth, legitimise newly-made fortunes, and show evidence of new-world culture by reference to the collection of old-world artefacts. Amassed initially around traditional core collections of antiquities, old masters and nineteenth-century paintings, the Americans also began to add Asian art and the Impressionists.

The ultimate effect of this new axis of purchasing power meant that some areas of art history all but dried up. By the beginning of the twentieth century, a new museum was unlikely to be able to able to pretend to anything approaching an encyclopaedic re-telling of art history, and gradually curators began to consolidate their collections around perceived areas of ‘strength’; examples of a particular movement, or the work of a single artist. This (albeit slowly) freed museum architecture from its rigid didactic progressional plan, although it wasn’t until Rogers and Piano’s Pompidou Centre (The Centre d’Art et de Culture Georges Pompidou, Paris 1977) that the mould was truly broken. [14]

The second development to reshape the course of ‘modern’ art museums was the Museum of Modern Art (MoMA), New York (1939, architects Philip L. Goodwin and Edward Durrell Stone). Conceived by its first charismatic director, Alfred Barr, as a ‘torpedo’, its nose “the ever-advancing present, its tail the ever-receding receding past," [15] Barr’s idea, in indirect answer to Gertrude’s Stein’s critique that one could either be modern or a museum, but not both, was that the museum would continually de-accession works as they ceased to be contemporary. While there were early attempts at this, it never really happened. But the radical nature of MoMA’s project, in terms of contemporary museum development, lay in Barr’s famous pronouncement that the architecturally Modernist Museum would be “a laboratory; in its experiments, the public is invited to participate." [16]

Museums have an interesting relationship with the new, as Barr’s failure to de-accession would suggest. As popular a cliché as is the ‘cathedral’ one, is that art museums, contemporary and otherwise, are both ‘dormitories’ and more forcefully ‘morgues’ for the art in their collections. But there is a paradoxically positive nature to the collecting and filing-away of art, in that it liberates us, as makers, from repetition of the past. After the Russian Revolution, when the new Soviet Government expressed concern for the old Russian museums and art collections, Kasimir Malevich wrote a protest to encourage their destruction. “Burn all past epochs," he announced. And if they really wanted to, he suggested storing the ashes of Old Masters in jars in a pharmacy, where those so minded could still go and finger their charred remains. In an earlier text, Malevich had remarked that it was impossible to paint the “fat ass of Venus" any more, and that something new had to be made. But, as philosopher Boris Groys argues, it is precisely the preserving of the Masters that frees us from having to repeat Venus’ ass, and makes the replication of old styles, conventions, and forms unnecessary. [17]

Given that today’s art museums are the inheritors of traditions of delight, of entertainment, of education, of colonialism and imperialism, of artistic freedom, of paradoxical release from the tyranny of past forms, and increasingly of urban regeneration and social inclusion: to what end – of all these strands – should their architecture be driven? In a reductive sense, according to Vito Acconci, museums are built the way the public stands in front of the art object. [18] But museums also bring you to that art object, and add their own traditions to the aesthetic assumptions and cultural baggage that one brings to the act of viewing. Within the essential architectural vocabulary of art spaces – including controllable natural light, good storage, clean spaces, a certain amount of height, flexible spaces, progression of rooms – a developing new lexicon is attempting to create spaces for all the new forms of art; forms that move beyond the frame and have climbed down off the plinth. Today’s art spaces conspire to create freedom and inspiration, rather than merely educational shelter and warmth for art, although in some cases a confusing new scenario is developing in which “the experience of place is replacing the experience of art." [19]

So where does all that leave the architect of today’s art space? As Michel Foucault has pointed out, space is never empty, never neutral, but “always saturated with qualities," [20] and in terms of the idea of ‘presence of absence’ which the stealing of the Mona Lisa underlined, the white cube’s presence of absence all the more strongly calls up the presence of the critical and art-historical apparatus that has determined it over its 200-year history. Attempts in the sixties and seventies to shake off this baggage by colonising warehouse spaces for art largely failed as the weight of the museum’s history clings more strongly than institutions, like the DIA Center in New York, would want to think.

In fact, the weight of the historical antecedents of the modern museum often threatens to present architects with a continuum of compromise. In 1943 when Solomon R. Guggenheim presented Frank Lloyd Wright with the brief “that the museum should be unlike any other," the art museum finally broke away from the traditional design of corridors and enfilades, yet even in his radical designs Lloyd Wright’s museum still presented the visitor with a single prescribed route through the works on display. And the strength of the traditions of the Louvre, the Vatican and the Ufizzi continues to influence both curators and architects. Richard Meier’s J. Paul Getty Museum (1984-97) in Los Angeles had the potential to be one of the most fully realised expressions of the architect’s vision for a neoclassical clarity. Yet it is compromised by the Museum’s lack of faith in Meier’s ability to meet the aesthetic requirements for the collection’s display. “We need a museum building that plays skilful accompanist to the collection. The building should subordinate itself to the works of art in the galleries, assert itself with dignity and grace in the public spaces…" [21] Consequently, New York architect and decorator Thierry Despont was commissioned to clad the walls of the gallery in muted fabrics and the floors with parquet, an arrangement which favours neither tradition nor modernity.

As architects respond to developments in contemporary art (larger areas balancing intimate spaces, rooms for the exhibition of digital art, installation, etc.), art works are given form and reading by the spaces they inhabit. Architecture impacts on and informs how we experience art, and crucially in site-specific works and specifically commissioned exhibitions, how work is made. Thus in addition to providing a space for the display of art, the architecture of art museums now contributes to its definition. Curators as well as artists and their art can now become characterised by the museum’s architectural spaces, as the museum involves itself in the relationship between curator, artist, work and audience.

Artists have often found the architectural presence of the museums where their work is displayed difficult to come to terms with. In 1956, artists including Milton Avery, Willem de Kooning, Philip Guston, Franz Kline and Robert Motherwell wrote an open letter to the Guggenheim trustees saying that the interiors of the New York museum were “not suitable for a sympathetic display of painting and sculpture." In 1958, in his last written words on the subject, Lloyd Wright countered such criticism with the statement that his building was a “genuine intelligent experiment in museum culture." Closer to home, artistic ambivalence about architecture is expressed in a review of the Model Arts Centre (renovation and extension architect: McCullough Mulvin, Sligo 2000): “The seven million pound collection will be left to impress without being outdone by the architecture" (Sheila Dickinson, CIRCA 95, 2001).

But should a museum be an exhibit in its own right? I. M. Pei’s celebrated East Building of the National Gallery of Art, Washington D.C. (1978), created a vast and impressive atrium space after which the exhibition galleries seem small, dark and often confusing. “The East Building itself has become the primary attraction rather than the art on display," notes Poyin Auyoung [22] in a discussion of the general change in the modes of usage for museum space. The Lowry is described as a “ must see tourist attraction – not just a venue but a destination," [23] and in a move even further from an idea of the central role of art in the museum space, Meier (perhaps due to an understanding of the kind of treatment which resulted in the mess of his J. Paul Getty Museum) wanted to officially open his Museum für Kunsthandwerk in Frankfurt before any of the art was installed at all.

Another development affecting the way architecture is perceived is increasing popularity of the coffee-table architecture book. The rise of new art museums as tourist destinations has accelerated this; signature architecture is seen and understood more frequently in postcards, and in photographs in books and glossy magazines, than in physical reality. As we make artists out of architects, we make architecture into two-dimensional images. Architecture, which has always implied users, is depicted like installation art, without people in its spaces. Famous buildings are deemed successful if they photograph dramatically, rather than functioning well. At its most influential (when it first opened) the majority of people discussing and referring to the Guggenheim Bilbao ‘knew’ it only from secondary images. This new way of looking at and understanding architecture subjects the spatial, saturated qualities of the museum or gallery to the more impoverished aesthetics of linear perspective. These emotional spaces, where art is viewed, appreciated, and sometimes understood, become pictures in their own right, and the artworks mere figures in the picture plane. A Serra sculpture in Bilbao takes on the same role as an apple in a Cézanne, and only certain forms of art emerge from that process well.

It is unsurprising that there is often an uneasy element to the relationship between architect and artist, both engaged in the visual creation of an aesthetic, both subject to the compromises of site, materials, finance and patronage. The essays, arguments and comments in this book take up these issues, aiming to illuminate the discussions. They bring closer the disciplines of art, architecture, curation and criticism, which together make up the fabric of the environments we inhabit, respond to and in which art is made. Chapters explore the process of commissioning a building from different perspectives, essays inquire into how space works, case studies investigate what we have, and the Inspirational Spaces? section looks at what might be. Concluding the book, a directory of art spaces, from the purpose-built to the ad hoc, sets out the architectural backdrop against which these discussions and debates are unfolding.

Until now, these architectural and artistic debates have taken place in parallel, and yet they are contingent upon one another. Changes in architectural materials mirror changes in artistic media and scale. The creation and the realisation of the Guggenheim Bilbao would have been impossible without the development of computer-aided design programs (made originally for the construction of fighter planes); responding to the architecture, its vast spaces house commissions by Sol le Witt, Richard Serra, Jenny Holzer and Francesco Clemente. The Bilbao Guggenheim accommodates work on a scale that it would be impossible to show in all but a few museums worldwide. And it is this symbiosis which points to the potential held by the challenges both art and architecture offer each other: spaces and creations whose notional limitations are constantly called into question by the developments and interventions of one another. Called into question, proved false, razed and reset until the boundaries are broken again.

Architects have always played a key role in the development of this debate, both through writings and discussion of theory, and through their creation of spaces in which these discussions take place. By widening the field of participation in architectural criticism, and by bringing the writings of curators and critics, artists, architects together in this book, the aim is to explore some of the hows and whys of art and architecture, and to create further discussion among those who build, use and inhabit our art spaces. Whether they wear suits, and whether or not they can paint.

Gemma Tipton is a writer on art and architecture based in Dublin and editor of Contexts magazine.