Maebh O’Regan has been in conversation with artist Mary Burke, who is currently showing at Draíocht in Blanchardstown.

Mary Burke’s studio is located in the attic storey of a building situated in St. Mary’s Abbey, off Capel Street, an area that was once at the heart of fashionable Dublin. The building originally belonged to the Bank of Ireland, but all vestiges of its former mercantile function are now eradicated and the structure boasts a warren of artist’s studios, each with its door tightly shut. There are, however, a number of open spaces; these are the service areas designed to facilitate the common need for photography, framing and storage. As we walk upstairs Burke explains the origins of the group.

Mary Burke: New Art Studio Limited, or NAS, has been in existence since 1983. I was one of the founding members and it took a huge effort to get it off the ground. It still takes up a lot of my time as I have run the studio on a voluntary basis for twenty-one years, so I suppose you can say it’s ‘my baby’. Initially, it started out as a group of young NCAD graduates from the class of 1982 who were looking for workspace. Niall Wright and myself are the only original members left. We have had over sixty artists through the place over years, and so it has been a stimulating place to work. We started out providing individual studios for artists, but latterly we have expanded to provide communal facilities as well. To date we have eleven studios, a fully equipped framing workshop, a photographic studio and a digital-media facility. We really want to expand the digital media side of things as more of us use it in our work. We are lucky to have had revenue funding from the Arts Council on an annual basis since we set up, as well as several capital grants that have enabled us to establish our communal resources.

Beside the obvious economic and material benefits of working within a group, there is immense advantage of contact with other artists. You can get quite isolated working on your own all the time.

Climbing several flights of stairs we finally reach the uppermost studio tucked snugly beneath the eaves. This L-shaped room is well lit by three large Georgian windows. Easels, Daler boards, drawing equipment and boxes of pastels adorn every available surface, while pastel paintings – finished and otherwise – are stacked in an upright position.

The artist’s preoccupation with the urban landscape is immediately evident. Many works relate to the artist’s own home in Larchfield Road. Burke explains her attachment to the house that she “Has lived in for forty-four years." This house has an enormous emotional resonance for her, yet she does not regard it as “Particularly exceptional or distinctive" but rather “A sanctuary in the suburban jungle."

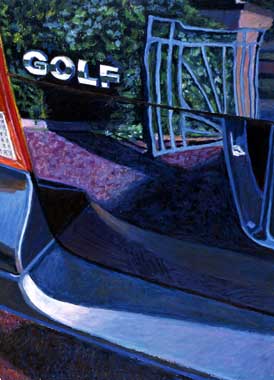

The artist’s work addresses the built environment, featuring the brick-fronted, semi-detached houses that line a street in Goatstown. These homes were all constructed to the same design, yet Mary Burke observes that “Each house is slightly different as its occupants put their own stamp on their residences, reflecting their personality and aspirations." Indeed, it is this very mundane aspect of twenty-first-century life that attracts the artist as “The familiarity or the ordinariness of the subject has always appealed to me." She continues to explain that “Unlike landscape, there is no tradition of painting suburbia in Ireland."

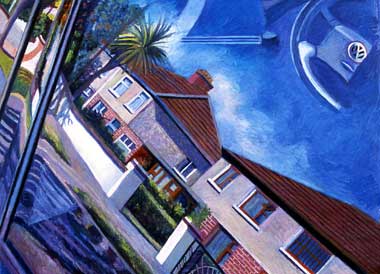

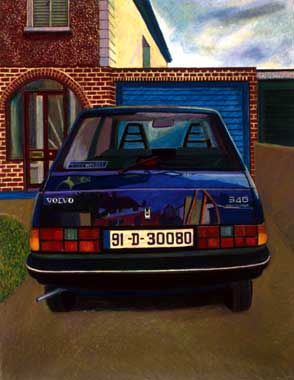

Glancing back at works dating from the 1990s, in particular the Larchfield Road images in the Suburbanscapes catalogue, the presence of the saloon car dominates. This box-like structure seems to echo the landscape reflected in the triangular glass of a street lamp, or in the rectangular façade of a house and the regimental wrought-iron work of the ‘sunburst’ pattern in the garden gates. As the cars depicted in her work have become less angular and more curved and sleek, the images and reflections have also taken on a more organic appearance. Is this approach deliberate?

The car in question is in fact a 1978 Datsun 180B. It belonged to my father and it was the car I learnt to drive in. It featured in many of the paintings from the early ’80s right up to 1990. You are right to suggest that the entire compositions in the earlier works are more angular. The move to softer lines in later paintings happened partly because the newer cars are more curvy, but also as a result of a concerted effort on my part to inject more atmosphere into the works.

I have always loved cars. When I was a young child I had a toy steering wheel attached to the end of my cot so that I could pretend to drive. I also had quite a few Dinky, Corgi and Matchbox cars, some of which I still have. The car as a subject is an extension of suburbia; therefore it is inevitable that it would feature in any body of work based in the suburbs.

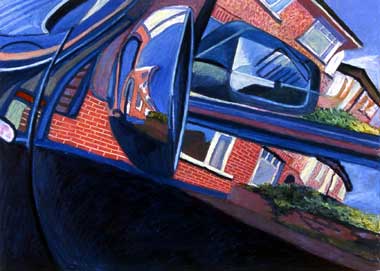

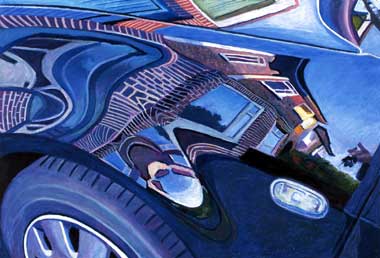

Burke also suggests that the structure of the car may be regarded as a starting point for a more complex approach: “If you stare into the bonnet of a car for several hours you see it differently to viewing it in a fleeting glance. There are amazing distorted reflections in vehicle’s bodywork which have provided me with numerous starting points for compositions."

Transport and travel appear to be a subtext in her work, as subjects addressed by the artist include depictions of a city bus, cars and an airport terminal. These various methods of transport appear to be a metaphor for daily living. “They tie in with the whole suburban thing as we seem to spend more and more time in transit. Thankfully, I now travel by car, as opposed to using public transport, which I find much more stressful." She goes on to explain: “However, these subjects: buses, cars, and airport buildings appeal to me on an abstract level too. They all have nice shiny surfaces which supply endless combinations of distorted reflections that are ideal fodder for painting."

As the name Mary Burke is synonymous with oil pastel I asked the artist what prompted her exclusive use of this media?

I painted in oils right throughout College, using pastels only for my preparatory work. We were encouraged to paint on a large scale. When I left NCAD I used to paint in oils for many years but over a period of time I increasingly favoured working on a large scale in oil pastel.

Burke’s use of this medium is distinctive in terms of scale and subject matter, as traditionally pastel painting is reserved for smaller work and portraiture in particular. She explained that she acquired a small box of oil pastels when still at Art College. It was still a relatively new medium then, and she was not given instruction in their use.

The pastel I use is not the traditional soft pastel employed by Degas, but rather a medium known as oil pastel, which is about fifty years old. The colours are more vibrant than in the traditional pastel and can be worked and reworked in a way that is similar to oil paint. Pastels allow you to draw and paint at the same time. You have the control and directness of the drawn line as well as being able to build up blocks and layers of colours.

Burke has been the recipient of a number of residencies both in Ireland and abroad. In 1993 she visited the United States for the first time, courtesy of a fellowship endowed by the Vermont Studio Center. This visit to Vermont was exceptionally stimulating. “There was heavy snow for most of the time that I was there and that, coupled with the strong light, provided amazing shadows." The architecture was very different from the Dublin suburbs, there was “an entire village consisting of clapboard buildings." The six weeks spent in Vermont were extremely productive. “It was like nothing I had ever experienced before, except in the movies. The result was that I produced fifty-two pieces and came home exhausted."

One of the principal characteristics of the artist’s work is her saturated, startling use of colour. This broad palette changes in reaction to the light and mood; for example, Twilight in Vermont (1993) contains essentially the same palette as a number of works in Semi-detached Reflections , yet the drawing and colour massing conveys a very different message. The artist explains how she achieves this ’emotional impact’ through colour.

I think most of us have sensitivity to a certain colour range. This is subjective and personal to each individual. I don’t think that it is too surprising that I would have a similar colour palette for two completely different subjects. The difference in the colour used is slight but significant and shows the difference between the more even Irish light and the sharp contrasts in North American light.

An earlier painting, School corridor, commissioned by the Arts Council for the School Show in 1986 and featured on the cover of An Múinteoir in the Spring of 1987, depicts the school the artist attended, Our Lady’s Grove, in Goatstown. This atmospheric piece illustrates a long, tunnel-like space with what at first appeared to be a human figure suspended in space at the end of the vista. (Burke later informed me that this is a statue of the Blessed Virgin – an apt motif considering the moving-statues epidemic in Ireland in the mid-1980s). In this work the calm blues, purples, maroons and yellows should convey a sense of comfort and warmth, yet instead they induce a feeling of threat and menace. Structurally the work had some resonances with Brian Maguire’s oil painting The foundation stone, mental hospital, 1990 (Douglas Hyde Gallery), a work that also induces a sense of panic and fear. When I mentioned the similarities to the artist she introduced me to an interesting theory. She referred to Michael Foucault’s book Discipline and Punishment: The Birth of the Prison, a text which puts forward the idea that many public institutions – the school, the work place, and the hospital – are all predicated on the same model, namely the prison.

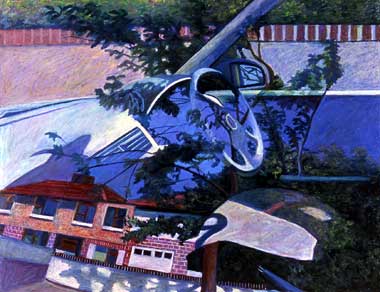

There is a radical difference between the artist’s earlier pictures, where classical perspective played an important role, and the kinetic nature of the new body of work that has been prepared for exhibition under the title Semidetached Reflections . This change in approach is due to new developments in Mary’s art-making practice, which has evolved over the years.

I used to work totally on site with pastels and develop the work into a larger oil painting in the studio. More recently with the car painting I started using both the digital stills camera and a camcorder to help select compositions. The camcorder especially gives me numerous options which I then download onto the computer and adjust in Photoshop. The computer has become a sketchbook. When I have selected my composition I draw it on a primed board, outlining the subject in pencil and moving on to pastel. There follows a slow build up of many layers of colour. The colours sit on top of one another so the mix is optical. This tends to provide a luminosity more readily than that achieved with paint. The subject to some extent dictates the methodology. If I were dealing with a more organic topic I would probably employ different methods.

Looking at an unfinished painting on the easel featuring the reflection of a cityscape in the windscreen of a car, one is immediately struck by the different manner in which the artist has approached the man-made objects as opposed to the natural environment. Hard surfaces, such as the plastic texture of the steering wheel, are meticulously delineated with mathematical precision, and this contrasts with the more organic objects, which are lyrically sketched in using broad, rhythmic lines. The whole composition writhes and flows, challenging the viewer to interpret the scene.

It is a case of taking a fresh look at something so familiar that it almost goes unnoticed.

Semidetached Reflections marks a crucial turning point in the artist’s career. The collection of works is on show in the Draíocht Gallery in Blanchardstown between 27 October and 27 November 2004. It promises to visually delight and stimulates the viewer into questioning suburban living in the twenty-first century.

Maebh O’Regan is a graduate of Trinity College Dublin with a Bachelor of Arts Degree in the History of Art and Classical Civilization; she continued her studies in the National College of Art and Design where she was awarded a Ph.D. for her thesis on the nineteenth-century artist Richard Moynan; she has been lecturing in NCAD since 2000; the focus of her current research is nineteenth-century political art and contemporary Irish female artists.

.jpg)