In 1992 the artist Louis le Brocquy (b.1916) was granted Ireland’s highest cultural distinction by Aosdána, that of the rank of Saoi. 2 This honour was in recognition of “his creative work which has made an outstanding contribution to the arts in Ireland." 3 Ten years on his painting A Family (1951) is displayed in pride of place in the National Gallery of Ireland (Fig.1). This laudable celebration of an artist’s talent by his own country men and women in fact marks ‘closure’ on an earlier history of rejection. The pinnacle of that negative reception was the reaction to A Family at the time of its production. Now acknowledged as a highly significant work in the history of 20 th-century Irish art, the response to it in Dublin in 1951 / 52 was decidedly mixed; from recognizing it as “a major work of art" 4 to denouncing it as “a diabolical caricature." 5 This article traces the history of the painting, particularly in relation to its reception at the time of its production. What precisely disturbed viewers about le Brocquy’s interpretation of the theme and resulted in its being rejected by the committee responsible for acquisitions at Dublin’s Municipal Gallery of Modern Art? The painting is also considered within the broader context of the place of modernism within a distinctive Irish cultural identity.

An oil on canvas, almost two metres wide, the picture depicts a family group in faux-cubist style. The mother, lying on a table, leaning on one arm, stares out with quiet dignity while a menacing looking cat peers out from beneath the draw sheet. In the background the father sits, head bowed, in a pose suggesting total dejection. He appears to be oblivious to the small child holding a bunch of flowers; a symbol of hope. The three somberly painted figures inhabit a grey concrete bunker, lit by a bare bulb. The theme of this disturbingly bleak work is the nature of individual isolation and the breakdown of societal norms. Le Brocquy states:

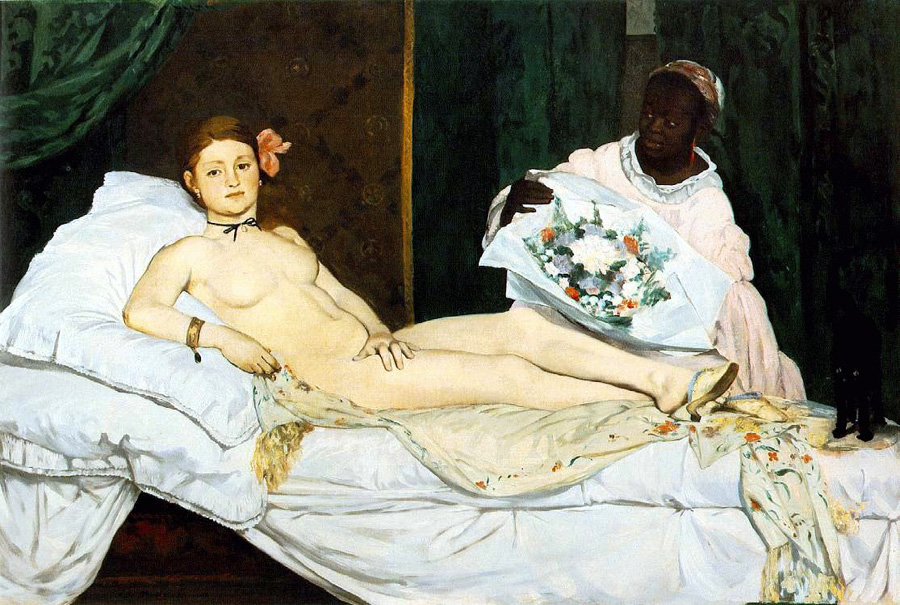

I have always been fascinated by the horizontal monumentality of traditional Odalisque painting, the reclining woman depicted voluptuously by one Master after another throughout the history of European art – Titian’s Venus of Urbino, Velazaquez’ Roqueby Reclining Odalisque in her seraglio and finally the great Olympia of Edouard Manet celebrating his favorite model, Victorine Meurent.

My own painting A Family was conceived in 1950 in very different circumstances, in face of the atomic threat, social upheaval and refugees of World War II and its aftermath. The elements in its composition correspond in some ways to those of Olympia, if not to Manet’s cool sensuality. The female figure in A Family may be seen to take on a very different significance. The man, replacing Manet’s black servant with bouquet, sits alone. The bouquet is reduced to a mere wisp held by a child. The Olympian black cat in turn becomes white, ominously emerging from the sheets. This is how A Family appears to me today. Fifty years ago it was painted while contemplating a human condition stripped back to Paleolithic circumstance under the electric light bulbs. 6

A Family was first exhibited along with works in a similar style by the artist in London at the Gimpel Fils Gallery in June 1951 and later in December at the Waddington Galleries, Dublin. 7 The show elicited much praise from eminent critics including John Berger and Eric Newton. Writing in the Art News and Review Berger noted:

His style has developed and changed; his colours are pale and severe – the Family is mostly grey; his forms, in their movement both across and into the picture, are precise. This finesse implies – because le Brocquy’s motive is always human – a tenderness which is not sentimental, and a sense of wonder which is exact; one thinks twice about the quite ordinary but in fact miraculous construction of any man’s back, having looked at the father in the Family . 8

Artist Anne Madden writes of le Brocquy’s theme as the human condition being “stripped of irrelevance." 9 This ability “not to seek to evade simple but difficult problems by relying on the grandiose cliché" was one also admired by Berger. Eric Newton, reviewing the work of a number of artists in London in The Listener, singled out le Brocquy as “a lyrical artist with an exceptional evocative gift" and an illustration of A Family was included in the review. 10 The painting was also featured during a talk on the BBC Third Programme.

The response to the Dublin show the following December was decidedly mixed. On the one hand there was open hostility to le Brocquy’s work, while on the other, a small group of interested art lovers were prepared to present A Family to the Art Advisory Committee in charge of acquisitions for the permanent collection at the Dublin Municipal Gallery. 11 It was refused. 12 The sharply divided opinions on the painting and its rejection by the Committee bring into focus the polarization of views of those interested in the visual arts at this time. There were two critical camps; the traditionalists who constituted the majority of the art establishment in Ireland, and the small but highly active circle of those promoting modernism and contemporary art. 13 Each group held firm convictions on the subject of what constituted ‘Great Art’. 14 Medb Ruane has stated that A Family represented a real challenge to the conservative art establishment, some of whom “had not yet come to terms with Post-Impressionism, let alone modernity." 15 For the traditionalists this challenging visual depiction was repugnant. It went against conventional notions of what constituted appropriate treatment of high-art themes. 16 Accordingly, all subjects should be treated with the supposed dignity and empathy befitting the noble art of painting and social themes should be kept within the bounds of propriety.

The artist’s image of stark reality in the shape of the terrifying uncertainty of the post-War era and the resultant isolation of the family unit shocked rather than comforted. One letter writer to The Irish Times stated unequivocally that the picture in question is as remote from beauty as the utmost stretch of mortal imagination can conceive. The figures are bestial, horribly misshapen with heads and faces of idiots. If ordinary people met such figures in the streets they would flee from them in terror. 17

The critic Tony Gray saw no tenderness in the forms portrayed. 18 Rather he felt that they were “depressing and frightening" and the sombre palette merely “enhanced the despair of his theme." The Evening Herald headlined its review “What is it all about" and castigated the le Brocquy exhibition for representing what it called “the left in art" (an oblique reference to modernism). 19 The artist was accused of having gone the way of everything sensational, shallow and ephemeral. The ‘Man About Town’ column in the Evening Mail believed that the whole composition was “bewildering and repulsive" (the length of the woman’s neck seemed to be especially abhorrent!). A rhetorical question implying a negative reply was posed, “What is the aesthetic value of these distortions"? 20 An editorial in the same newspaper broadened the enquiry to a consideration of the genuine value of modern art in general. Did it really contribute to culture or was it “a translation into farcical terms of all that is great and good in the work of the old masters?" 21

As the artist has made clear, A Family was following in an age-old artistic tradition in art: depictions of reclining figures. Indeed on close examination the elements in le Brocquy’s composition correspond in many ways to those of Manet’s painting (Fig.2). Each of the principal figures is presented in a prone position while propping themselves on one elbow in order to engage the viewer more directly. Their unswerving gazes are uniformly disconcerting. A number of the ‘props’ in the paintings are similar; the cat, the sheets, flowers, and the bed. There are also references to other great paintings. These are alluded to by critic John Russell, who recognized that le Brocquy had caught the mood of the times in his painting. 22 The bare bulb is reminiscent of Guernica and the reclining figure of Henry Moore’s early sculpture and drawings. Le Brocquy, in the manner of earlier artists, like Manet and Picasso, was working in the ancient tradition of the ‘major painting’; a work that summed up what a painter stood for and showed what he could do when at full stretch. And as in the case of earlier artists, critical reception to innovation depended largely on the viewer’s own deeply held aesthetic ideals.

Those who admired le Brocquy’s ‘major painting’ felt that its detractors were judging it solely in terms of its academic realism or rather lack of it. 23 It was argued that the artist painted in the way that he did for the only reason any creative person creates anything; because he feels he must, and because he enjoys doing so. Furthermore it was pointed out there was more than one way of judging the artistic worth of a painting. Slating it because it did not reflect reality was unjust. Apart from any literal significance which a painting may or may not have, it can be appreciated for its formal qualities (the composition, colour, line and application of paint). The protests by members of the Irish Exhibition of Living Art (IELA) on its rejection by the Art Advisory Committee extended the debate to other issues. 24 For instance, the make-up of the Art Advisory Committee was questioned. In spite of the fact that the IELA actively promoted modern contemporary art, none of its members had ever been invited on that particular committee. On the other hand, the opponents of such art were represented on it.

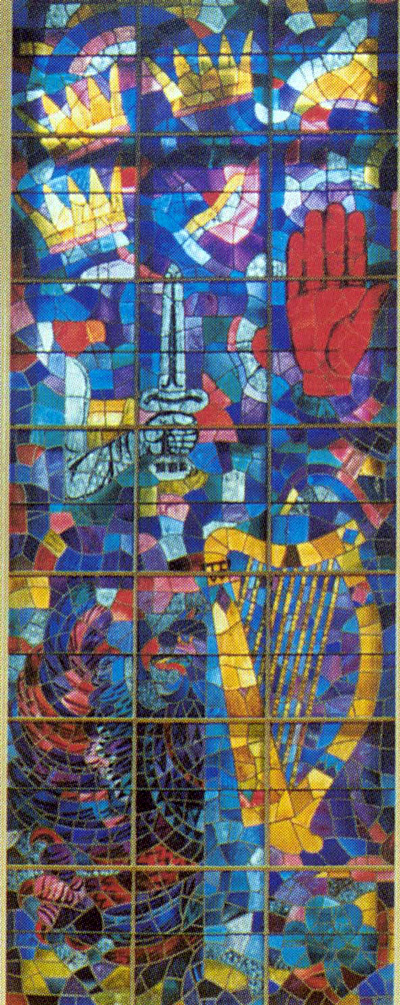

Oddly enough, as was pointed out in a letter to the press 25, the ‘contemporary school’ was never overlooked when exhibitions sponsored by the Cultural Relations Committee of the Department of External Affairs were sent abroad. This same point was seized on by another interested member of the public. 26 The writer was critical of the fact that collections of paintings by modern Irish artists were being sent at considerable expense to the United States, yet it remained impossible for visitors to Ireland to view any such collection in an Irish public gallery. He had hoped that the gift of A Family would initiate a collection of contemporary art in the Gallery “which this country lacks." The fact that the State appeared to have no difficulty in promoting innovative, even abstract works to be shown abroad may seem somewhat puzzling. 27 One explanation is the content of the work. If stressing aspects of ‘Irishness’, any misgivings about a modernist treatment of style were usually suspended. For instance, Mainie Jellett’s Achill Horses (Fig.3) and Evie Hone’s Four Green Fields (Fig.4) were commissioned for the 1939 New York World Fair. Both of these works, which project an image of Ireland as wholly independent and a rural utopia, were deemed acceptable art. 28

This unusual flexibility, when examined within the context of Irish cultural identity, reveals the problematic role of art in newly independent Ireland. In this post-colonial period, and in keeping with other newly emerged nations, being ‘different’ was an imperative. While there was broad agreement by cultural enthusiasts about creating a distinctive Irish art and literature, how best to express it visually and verbally was hotly debated. 29 At official level Ireland was promoted as a homogeneous nation, rural, Irish-speaking, Catholic, with roots in the Celtic past. The proliferation of West of Ireland paintings by artists like Paul Henry, James Craig and others served, witting or unwittingly, to give legitimacy to this construct. State commissions for home consumption, mainly in the form of portraits and monuments of historical worthies, were almost invariably factured in an academic realistic style; a reflection of the majority outlook that this style best articulated Ireland’s visual cultural identity. 30

An art not tied “to the evocation of a harmonious Irish world narrowly conforming to norms," created concerns for conservative art lovers. 31 Indeed such was the reaction that it was often considered not only alien but anti-Catholic! Perhaps the most interesting example of this extreme view is connected with the Rouault controversy in which Le Brocquy was an active participant. Purchased byFriends of the National Collections of Ireland (FNCI) and offered to the Municipal Gallery in1942 George Rouault’s Christ in His Passion was refused by the Art Advisory Committee (Fig. 5). One member believed it to be “offensive to Christian sentiment," another stated that it was “a foretaste of Hell." 32 For his part le Brocquy appealed for the decision to be reversed while at the same time reprimanding Sean Keating for insulting the name of Rouault.

Modernists did not believe that a distinctive Irish art had to consist of countless scenes of peasants, thatched cottages and Irish scenery and little else. 33 Their subject matter was not exclusively focused on ‘Irishness’ in terms of its content and their ‘language’ of style was grounded in avant-garde ideas emanating from abroad. In le Brocquy’s case his art at this time stemmed from a preoccupation with the human predicament. 34 Paintings like A Family expressed a concern for the whole of humanity rather than exclusively his own countrymen and women. But it would be a mistake to think that the artist had little sense of a national identity. As a child growing up in Ireland he remembers not feeling particularly Irish. 35 But once he left the country that irrevocably changed. 36 His early European experience convinced him of his own nationality. “I became vividly aware for the first time of my Irish identity to which I have remained attached all my life."

The future history of the picture was destined to be one of great critical acclaim internationally and nationally. In June 1956 le Brocquy represented Ireland, with the sculptor Hilary Heron, at the Venice Biennale. Among the works shown was A Family . 37 It was awarded the Nestlé-endowed Premio Aquisitato and the painter’s international reputation rose accordingly. Ironically, in view of the picture being rejected by the Municipal Gallery, it was the first public gallery to accept for exhibition another of his earliest works, Southern Window, and it hosted an important retrospective of le Brocquy’s work in 1966. In the Foreword to the catalogue Eithne Waldron (Curator in 1966) expressed the particular pleasure that Dublin Corporation had in making the exhibition rooms available for the retrospective. 38

Presented as a gift in 2001 to the National Gallery, A Family is rightly recognized as a seminal painting in the history of 20 th-century Irish art. 39 It is not only an important transitional work in the artist’s oeuvre but one anticipating modernism as an everyday style in Irish art. All of this is implicitly acknowledged in its being on display to the public. To date, the exception to the policy of only displaying work by dead artists in the Gallery is the continuous acquisition of portraits by contemporary artists for the National Portrait Collection. Le Brocquy is the only living artist to have a work on show as part of the permanent collection. As Medb Ruane has pointed out, the prophet has finally been honoured in his own land. 40

Dr. Síghle Bhreathnach-Lynch is Curator of Irish Art at the National Gallery of Ireland, Dublin.