|

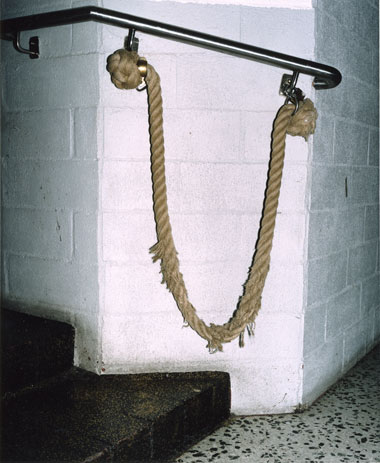

| Lars Tunbjörk: Vinter, installation shot, Moderna Museet, 2007; courtesy the author |

In the basement floor of Moderna Museet in Stockholm lies an exhibition of two projects by Swedish photographer and photojournalist Lars Tunbjörk. The two projects are entitled Vinter and Home and the exhibition then Vinter / Home . Tunbjörk is a Swedish freelance photographer with a huge international reputation. In the exhibition in Moderna Museet, Tunbjörk has explored issues and themes relating to his home town and country, and this work plays upon the unavoidable capacity in photography to be culturally specific. “Photography is an index of values. Both in production and consumption. Photographs are matter in cultural movement. In order to live, they include their time and space.” [1]

Tunbjörk has spoken before of the Swedish tendency towards melancholia: “A major aspect of Swedish culture, its literature and its films is this strong melancholia, and I tried to work with that.” [2] Melancholy is the overwhelming feeling played out in both of the projects in this exhibition.

Although exhibited together, the two projects are shown in two different rooms, making them, in reality, two separate exhibitions. Vinter stems from the common depression caused by Sweden’s dark winter, and Home is a personal journey for the artist through his childhood home and neighbourhood, following the death of his father. In keeping with an understated sentiment, nothing is revealed of the decision to title one exhibition in Swedish and the other in English.

|

| Lars Tunbjörk: from Vinter; courtesy Moderna Museet |

The exhibition was something of a disappointment – not for the quality of the work, or the power of the subject matter, but for the shattered dreams of an idealistic visitor from a snowless land. Up to this point, dark, snow-covered winters had to me spelled Bing Crosby wonderlands, skiing and endless log-fires. Tunbjörk dispelled those illusions in one fell swoop. In reality, for many, the long dark months of winter in Sweden amount to depression, isolation and hardship. Many Swedes experience a sharp mood swing every six months, especially in the Northern regions, such as the city of Kiruna – one of the subjects of Tunbjörk’s Vinter project – where there is an intensely noticeable change from summer, when the sun never sets, to winter, when the sun never rises.

Vinter is certainly not a flattering reflection on Swedish society. Tunbjörk unerringly exposes that isolation and desperate depression felt in winter. Subdued and less humorous than his previous work, Vinter doesn’t capture the hilarious substance of everyday existence, but sad and pathetic winter realities. Likely reflecting his own bad mood, he doesn’t attempt to find beauty in the images; he highlights the dirt, the rubbish, the frayed edges.

The volume of images and subjects contained in this project is overwhelming – restaurants, homes and parties, front yards, roads and forests, businessmen sharing a joke, young lovers about to embrace, parents and children, pets and their owners, empty spaces and lively scenes with lots of people. It may even be difficult on first viewing to establish the commonality between the images in this project; however, there is a common vein, in that all of the images convey that particular lowness Tunbjörk associates with winter. The people seem desperate and come across as starved of social interaction; the houses are cheaply decorated and in poor taste; the pets are clingy; and as the camera moves away from the security of the indoor scenes, the sense of isolation and dread is powerful.

At first glance, images like Kiruna, 2004, look pristine and perfect. A smooth layer of pure white snow rests atop and in front of a wooden bungalow; to the unfamiliar eye, this looks like an altered photograph – the snow is almost too perfect. The two German shepherds outside the door bring us back to reality of isolation and the sense of insecurity it could bring. The viewer might also feel a sense of fading away from the little house: it may be a haven compared to the expansive wasteland created by the snow, surrounding it.

|

| Lars Tunbjörk: Vinter, installation shot, Moderna Museet, 2007; courtesy the author |

These two exhibitions are the output of a Swedish photographer working very much in the context of his own national identity. Vinter comprises very specific cultural and contextual signifiers, altogether unfamiliar to a foreigner from a relatively mild climate (much as we may complain otherwise here). Nonetheless, Tunbjörk has many other means of conveying his message successfully to that unfamiliar visitor, and he exposes the depressing reality of living without daylight. The outdoor images reveal hardships associated with snow, such as driving in bad conditions, or as in Stockholm, 2006, where a woman painfully pushes a wheelchair up a snow-covered path. The interior photographs are similarly dark, bleak, harsh and lit with artificial light.

Home is a project of memories and reflection. The photographer returned to his home city, Borås, following the death of his father and photographed his mother’s home and the surrounding areas, in a journey of reminiscence and reflection. This is a personal journey played out in the form of public presentation. There are lots of images of lawns, doors, fences, backyards and public paths. In the interior photographs are edges of couches and living-room corners. Only one photograph contains the image of a person, and even then, that person is shown from the waist down. The colours are very bright and playful, yet there is a sense of pain reflected through the works.

The photographs in Home are similar to the 1997 daytime photos taken by Richard Billingham for his Black Country series. Both photographers have explored the areas they grew up in, from the perspective of a recently changed attitude towards those places. Billingham’s photographs were taken at a time when he was realising that he could no longer be both successful and still live in the security of his hometown, and from this realisation his photographs are infused with a sense of longing and of loss. [3] Although the root of the project may have been different, Tunbjörk achieves a similar sensibility in his work.

|

| Lars Tunbjörk: from Vinter; courtesy Moderna Museet |

“I know that some people see it as a comment on the architectural environment or a middle class lifestyle, but for it’s not for me. I started the project after my father died and I began photographing inside his house. Then I started shooting the surrounding area and other similar places. It is a much more personal work. It is all about foggy memories.” [4]

Tunbjörk may describe his feelings towards the work as “foggy,” but much like the Vinter photos, the Home photos are far from foggy and treat the subject matter with a sense of stark reality. Despite the bright light and bright colours, Tunbjörk still manages to inject a a sombre mood. The work is extremely personal and Tunbjörk cannot but project himself into these photographs which are devoid of people. “The existence of the photographic camera allows man’s intervention to be reduced to a minimum, but at the same time it forces him to impose his presence at the moment of creation, to establish a living relationship with the subject, and to initiate a hand-to-hand struggle. He disappears behind the keyhole but he cannot separate himself from the door. His absence is his presence.” [5]

In Tunbjörk’s work there doesn’t appear to be an art agenda. Tunbjörk wanted to be creative, or to explore his father’s familiar territory, but the photographs themselves don’t purport to having any greater ambition than to just be. “Tunbjörk has portrayed a nation heading into late modernism – away from the Welfare State – but he does not have an overtly political message. He does not judge, does not add any long, explanatory captions, but is an observer who leaves it to the visual narratives themselves to generate questions in the viewer. His photographs thus serve as testimonies to the state of things, but without any claims of delivering the whole truth.” [6]

Tunbjörk uses an international aesthetic language to engage with national and personal issues, drawing on influences such as Walker Evans, Lee Friedlander and Garry Winogrand. Unlike many of these international influences, however, who moved quickly to capture real moments of movement or activity, there is a sense of calm and stillness to Tunbjörk’s work. He appears to have quietly recorded the still and the silence.

Hollie Kearns

1 Edmundo Desnoes, ‘Cuba made me so’, The Photographic Reader, 2003, Routledge

2 Lars Tunbjork quoted in ‘Lars Tunbjork, Safe from harm’, The British Journal of Photography website.

3 Richard Billingham, ‘Richard Billingham’s Black Country’, www.fusedmagazine.com

4 Lars Tunbjork quoted in ‘Lars Tunbjork, Safe from harm’, The British Journal of Photography website, www.bjphoto.co.uk

5 Edmundo Desnoes, ‘Cuba made me so’, The Photographic Reader, 2003, Routledge.

6 Anna Tellgren, curator, Moderna Museet, ‘Lars Tunbjork’s sense of snow’, Moderna Museet website, www.modernamuseet.se