|

| Brian Duggan: A long walk off a short pier, 2008; installation shot; courtesy the artist |

G126, located in the gritty fringe of Galway city, is occupied by Brian Duggan’s A long walk off a short pier. The gallery is dominated by an authoritative sculptural installation that rivals the urban austerity of the surrounding industrial estate. In stark contrast, the video work is situated entirely in rural environments. References to sublime and archetypal landscapes are made with the humour and contrary standpoint of a David Shrigley rather than the detached romance of a Casper David Friedrich. Iconic landscapes such as sea, mountain, or tree become backdrops for videotaped actions or performances, while Duggan literally up-ends and alters his viewpoint and consequently the viewer’s.

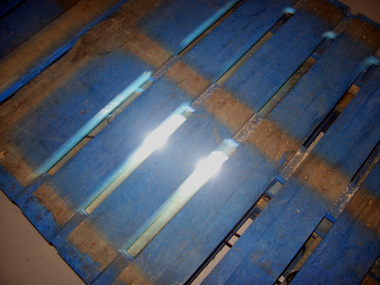

The moment you enter G126, you are asked to negotiate a strange and even disorientating space. Such sounds as a distant splash, a train whistle, a sighing wind, and an insistent panting cue us into a stage where exercises of considerable effort are made. A large catwalk-like pier traverses the room, viewing booths divide the space and house video projections, two televisions play contrapuntally across from each other, while a single, distant flatscreen lures the audience inside. The entire installation has a theatrical, stage-like quality: raw unpainted wood panels obstruct and reveal light and sound as you walk along an elevated, beautifully under-lit ‘pier’ constructed from blue pallets (borrowed from neighbouring cheese and tile wholesalers). While some of the works are framed still, others are attached to the artist or follow his actions. These videos – shaky, hand-held – recall the aesthetic of The Blair witch project [1], or the verité of reality television. Through this elaborate and crowded spatial transformation, Duggan provides the viewer with a physical experience. This is much the same as in previous works in Pallas Heights and the Hugh Lane, Dublin, where he lured the audience to comfortably lie down or dangle on swings to watch his videos. In engaging physically, the audience becomes ‘performative’. We not only view the work but experience it bodily. We are asked to re-site ourselves above ground, above our normal point of view, re-oriented to the landscape of Duggan’s work. We are turned in unexpected directions, in echoes of the central works. The disorientation is mirrored by the actions within the videos, which are projected or played on monitors stationed throughout the installation.

|

| Brian Duggan: A long walk off a short pier, 2008; installation shot; courtesy the artist |

In one video, Duggan seems, at first glance, to be standing. You then realize he is hanging upside-down, bat-like, from a branch. The monitor or the camera is flipped. You become fascinated by his effort to keep his hands at his side, flexing his arms with the effort it takes to make this exercise seem effortless. In these ‘extreme’ situations, he obliquely explores the human condition of survival and challenge, reminding the viewer of the tension between the body and the world at large. Absurd, physically demanding actions filmed and projected at deceptive angles are not a new theme for Duggan. His 2005 Hugh Lane offsite project During the meanwhile featured work with similar reasoning. At this year’s Burren College of Art Flicker show, Duggan exhibited LADDR, a piece showing a man climbing, even bungling, up and down a ladder. The ladder appears to hang precariously from the side of a building. Only it soon becomes clear the frame is upside-down, as is the performer. There is at once a deception and a humorously bizarre performance taking place. Whether the artist climbs endlessly up and down, upside-down or dangles forever in composure, a basic incongruity is at work here. The viewer is able to see beyond the jokey visual deceit and remain challenged. This work cannot be confused with the slapstick physical comedy of silent films. There is something allegorically existential and even tragic about these works.

Mid-way through the gallery, two opposite televisions show the same picturesque green landscape, a lone tree off to the left. Minutes pass. Suddenly on one monitor a figure runs into the frame, somersaults mid-screen and dashes on; simultaneously his motion is mimicked by the camera, just as quickly as it started we are returned to the idyllic landscape and original point-of-view. Moments later the opposite monitor follows suit, only this time he runs from the other direction. Is the camera following Duggan or is it negating his action, keeping him still? The ‘reflecting’ televisions heighten our uneasiness, as we turn our heads back and forth searching for the next action. This time we are not deceived, but thrown off balance and embark on the task of decoding his efforts. Duggan has set his old work in motion with a self-effacing and self-aware honesty. An iconic scene is disturbed, placing the viewer in the middle of a bewildering conversation, in which positional ‘normality’ is questioned.

|

| Brian Duggan: A long walk off a short pier, 2008; installation shot; courtesy the artist |

This absurd conversation continues in the show’s central pieces, two projections in opposite corners of the G126 white cube, both contained behind bare, not-quite-reaching-to-the-floor walls. The projections are visible, although not wholly watchable, from the end of the ‘pier’ sculpture and entice the viewer off, and into their respective viewing booths. To our left is LoafSugar, in which a camera fixed to Duggan records a journey up a mountain… backwards! Its simplicity is its strength, as it is literally shot ‘from the shoulder’. There is a theme of struggling and playing that is reminiscent of Fischli and Weiss’ Der rechte Weg (The right way) [2], where Rat and Bear trek up the Alps, delighting in the mundane and trivial. Similarly, Duggan’s wrong-way-round journey is dominated by gasps for air and a head-cast-down struggle for footing over stones and weeds. Shaky, dizzying and confusing, the work can prove a test to watch. In this way it is related to the Ken Fandell piece, It’s hard and I could use some help [3], in which he assembles, by fidgety hand, tiny plastic figures with such flawed human ineffectuality it reminds us of, at every moment, the limitations of our bodies. But with LoafSugar one is rewarded with a final relief as Duggan raises his head to the panoramic view of the Wicklow landscape, after finally reaching the windswept summit.

To the right is the video A long walk off a short pier [blindfolded], portraying Duggan’s inevitable misfortune. The artist marches to the end of a quintessentially Irish pier. At pier’s end he places a mask over his head and retraces his steps… backwards, then forwards, and back again. It is a countdown to comic disaster, foreshadowed by the show’s title and the viewer’s interaction with the installation itself. Ultimately a Beckettian aesthetic prevails, albeit via failure. This piece is the epitome of Beckett’s famous extract: “Ever tried. Ever failed. No matter. Try Again. Fail again. Fail better!” [4] When Duggan finally falls off his pier – blindfolded, his body language acutely present and sensitive to the space – we laugh with the release of tension at the much dreaded and anticipated fall . Once again the system set up by the artist backfires on the instigator. Like much of the show, the video’s playfulness has a double edge.

Vigorously masculine actions and images arise from all the work, quoting Mathew Barney’s performance of elegant, athletic prowess, or Teching Hsieh’s extended acts of endurance. Each video presents the physical efforts of the artist in relation to a natural or artificial obstruction. He sets up practical rules and boundaries, then tests out various feats of endurance: somersaulting, climbing a mountain backwards, blindfolded walking backwards on a pier. In these acts of stamina and courage, he humorously undermines any risk of self-aggrandizement by the utter futility of his actions and open, playful quality of his performance. The role of the artist also comes into question. By navigating these rural spaces and using his body to convey meaning, Duggan asks, ‘Is this process conceptual or physical?’ Stark and fundamentally minimalist, the protagonist pits his all-too-human efforts against the ‘meaningless’ though existential tasks. Yet Duggan is as serious as he is trickster. He takes us with him on self-prescribed struggles and leaves us with a droll and empathetic appreciation of these Sisyphean quests.

Áine Phillips is a performance artist and the Head of Sculpture at the Burren College of Art.

Jim Ricks is a Galway-based artist and Chairperson of G126.

With thanks to Phillina Sun.

[1] Blair Witch Project, dir Daniel Myrick and Eduardo Sanchez, Artisan Entertainment, 1999

[2] Pp 187-94. Peter Fischli & David Weiss / Flowers & Questions · A Retrospective . London: Tate Publishing 2006

[3] http://www.kenfandell.com/Pages/artwork.html#ItsHard

[4] p 7, Beckett, Samuel. Worstward ho . London: John Calder, 1983