Ken Fandell has visited Galway in the past, yet his show at 126, Between me and Galway Bay – a sort of portrait of Ireland – was constructed at a remove, from his native Chicago, via the internet. It mainly resembles the stuff you might Google the night before your holidays: Google Maps, simplified local history, folk music. The charm of the exhibition lies in its casually modest materials and references to a range of postminimalist touchstones from Steve Reich to Felix González-Torres. Yet in its own casual way it suggests the outline of a phenomenology that blurs the line between browsing and traveling.

Ken Fandell: Between me and Galway Bay, 2009, installation shot, 126; courtesy the artist

A theme that recurs is how the apparatus of internet-surfing become extensions of the senses. In his early Cartesian meditations, Husserl explains how a single die, for instance, is not apprehended internally as a complete image that represents the total surface of the die faces. Rather, the die appears as a continually incomplete manifestation of itself, where the perceived relationships between the faces extends to each view so that the sense of the whole is one that is temporal; while each view changes how the object is perceived, the whole appears as a synthetic unity between each view: both complete and incomplete.

On the invitation is printed a Google Maps screengrab that shows a marker pointing to Galway Bay, now curiously located in downtown Chicago. The marker, though, refers not to the actual Galway Bay (which the gallery nearly looks out onto) but an Irish pub that bears its name. It’s a nice joke, and a good introduction to an exhibition where even physical space itself becomes an absurd extension of web-based cultural detritus.

Ken Fandell: Between me and Galway Bay, 2009, installation shot, 126; courtesy the artist

It is this Chicago pub where Fandell begins his journey. Hoping to fulfill a fraction of the experience of traveling to the original Galway Bay, the artist walks from his home to the pub and points his camera upwards. The Sky above me and Galway Bay worked within the show as a kind of armature for the other pieces. It helped structure the room, dividing it. Both a floor and photographic piece, it embodied the dislocation that Fandell is more explicit and explicative about in other pieces.

In Fandell’s work, both real space and cyberspace are interposed. That perspective – no longer operating from the binocularity of natural vision, but from multiple and difficult-to-locate viewpoints – becomes fractured and disjointed. In some cases, the effect is prismatic, new valencies and qualities emerge from the play of distortions. The most notable example is the sound piece I first saw Illinois my own dear Galway Bay which loops and repeats two phrases. These comprise the title, from Frank A Fahy’s expat lament. As the piece progresses, it becomes layered with the same mantra sampled from about as many versions as Fandell could find on iTunes I’m guessing. While dissonant and discordant, the aural accumulation offers fascinating textures and moiré patterns of sound. In its primitive techniques, the work verges on a post-Napster pastiche of 60s tape music, such as Steve Reich’s seminal It’s gonna rain. A more appropriate reference, though, might be Boat woman song from Holger Czukay’s 1969 album Canaxis. Composed around a field recording of two Vietnamese women singing, Czukay’s experiment attempts to reconcile folk traditions and the advancing influence of technology within ’60s composition. However, Fandell’s concern is more spatial: within the confines of the headphones’ speakers, the numerous spaces of the recordings are flattened and fused, much like the discontinuous coincidence of the two places mentioned in the piece’s title.

Ken Fandell: No way to Galway Bay, installation shot, colour print; courtesy the artist

These interactions between spaces are set up by striking juxtapositions of three-dimensional sculptural elements, whether photographic or an image taken from a Google Maps satellite view, as is the case with No way to Galway Bay. This consists of an oversized print of the Atlantic highlighting the artists’ home, Chicago, and the site of the exhibition, Galway Bay. The way in which the crumpled paper sags away from the wall calls to mind the latex wall-casts of Robert Overby. Its jumbo-size is a small gesture, effective in highlighting the materiality of the actual paper as distinct from the different spaces implied by the image (the flat space of the computer screen, the depth of cyberspace and the actual image of the earth as stitched together from thousands of satellite images), as well as illustrating the distance traveled by the image, from Chicago to Galway. The piece easily fragments into so many spaces that it becomes a metonym for Fandell’s post-technological phenomenology.

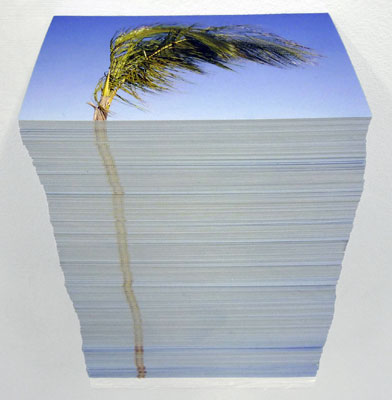

Ken Fandell: On the way to Galway Bay, colour postcards; courtesy the artist

It is in the jumps, fissures and ambiguous spaces generated online that Fandell’s pieces seem to exist. On the way to Galway Bay consists of a stack of postcards featuring a palm-tree. At first I thought it was just a joke, a flip aside to make sure you’re in on the joke: that America is just as susceptible to the distorting lens of the information superhighway as the Emerald Isle, just as prone to breaking down in simplification and misinformation. But as you take from the stack, shrinking its size, the negative space becomes part of the sculptural shape, a hollow space where the limits are ambiguous and temporal, and never apprehended in its whole.

The blind spots generated by this way of looking at the world will be obvious to almost anyone who has spent much too long on the internet, trying to search for a piece of information that should, by all assumptions, be easy to find. Fandell’s allusions to Man of Aran and Galway Bay are both tongue-in-cheek and symptomatic of the confused half-portrait that his skewed perspectives result in. Between me and Galway Bay revels in its own distortions and disruptions both ridiculous and sublime.

Tiarnán McDonagh is an artist based in Galway.