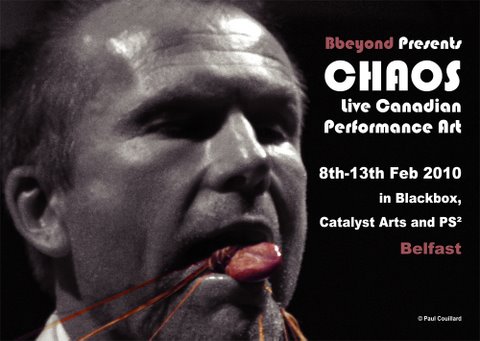

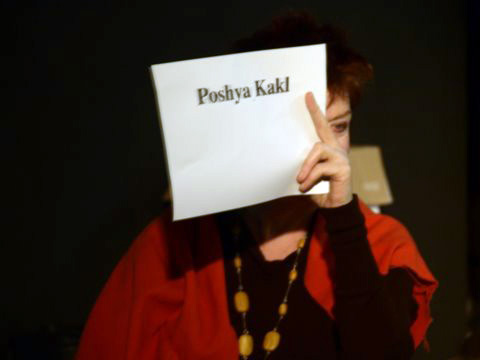

Ten Canadian artists, from Vancouver, Toronto and Montreal, performed each at one of the following sites: PS2, Catalyst Arts Gallery, Black Box, in the Glass Box at the University of Ulster, and on the streets of Belfast. Curated for Bbeyond by Sinead O’Donnell, Judith Price and John G Boehme, the event was a welcome addition to the Belfast art scene. Bbeyond not only brings in visitors from various countries, it also cultivates frequent workshops, meetings, and events for the enthusiastic home-grown young generation of performance artists who are, increasingly, being invited to take part in international festivals. The value of such activities comes into poignant focus, in relation to Poshya Kakl, a young Kurd from Iraq who could not travel to Belfast to perform in person when the authorities refused to grant her a visa. She turned that experience into a performance (Hopscotch) in front of the parliament in Iraq. The video documents of her recent performances received a screening in PS2. Her action at an entrance to a mosque in Iraq, playing a mouth organ dressed in red, filmed by a hidden camera, challenged Iraqi men’s privileged status. Her contribution to Chaos was the only one that honoured the name of political art. The audience in Black Box later carried cards with her name in her honour. (Fig 2)

Any embodied knowledge acquired by imitation involves changes and behaviour patterns that hesitate to fall into a system. Voices, poses, and gestures propel the narrative towards the context privileged by the artists’ intention. That intention fuses the time slot, site/ space, and interaction with the audience into a temporary context, or contexts. The imagined translates into the perceivable more often than not by producing a particularly foggy context of ‘being–with’, which charms the real and the present with a power of premeditated mood. A performance thus exposes its ‘naked existence’ before it exposes its political, judicial, moral and artistic values. Consequently, the artist’s intention and the viewer’s perception of values act, respectively, as a past and a future of a performance, as a script and as a trace. Only the ‘being-with’ approximates the ‘naked existence’ of the performance. It is thus not a satisfactory condition that I have not seen all the performances in situ. Instead, I work from primary sources: two disks with stills, eight video recordings and few random discussions with participants. As a trained historian, I feel comfortable with the demands of interpreting incomplete sources. Moreover, given the way performance art is delivered to a public, even as a viewer in a room, I would have an incomplete perception of the action. Depending on the quality of sound, of the lighting, my distance from the performer, and my viewing angle, I could see less than does the lens of the camera, often given a privileged position.

I recognise that the absence of my sensing the energy of the interaction in situ deforms my observation and discrimination, particularly in relation to the impact on the viewers.

I could see on the video tape that Irene Loughlin’s episodic structure increasingly lost the attention of many in the audience, whereas the same fragmentary process used by Shannon Cochrane, kept the audience engaged.

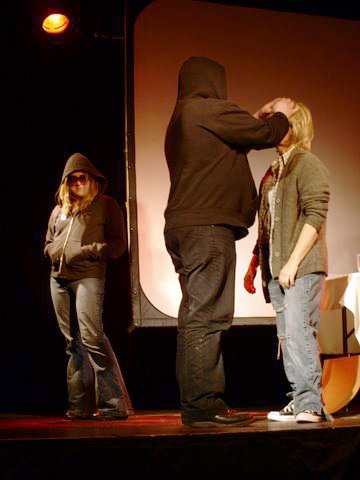

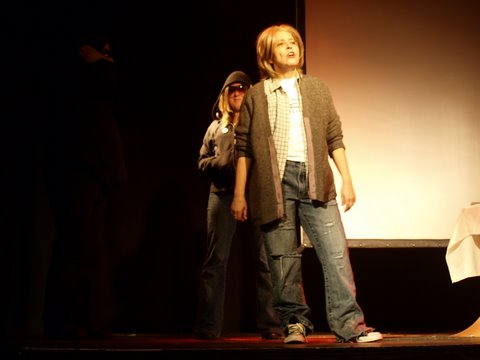

(Fig 3) Cochrane imbued her Festival-performance-festival with a slight parody. The particular episodes did not connect fluently, each stood on its own, disembodied both from the original and from each other. Re-performing has become fashionable. No amount of frequency will remove the dual difficulty re-performing insists on. Even the famous Marina Abramovic re-performing of Joseph Beuys’s iconic work, I find unsatisfactory. On the other hand, the re-performing of Allan Kaprow’s Take a chair, sit on it, leave a gift by San Diego students last year I found flawless and rewarding. In principle, re-performing is simply the case of original and a copy, or of a leader and a follower. The ‘naked existence’ mentioned earlier makes performance art a stronger opponent of re-performing, at least on two grounds: the time/ space element is a constituent of a performance, and cannot be re-performed; the physical presence, body energy, rhythm, facial expressions are rarely so documented as to allow a faithful copy. It can be successfully argued that we shall receive a variant on a theme. In that sense, re-performing is similar to citation/ quotation in painting for example. A single quote, however, does not guarantee that the intrinsic value of the original will not be lost. An added difficulty arises from different priming of the audience: those who know the original inevitably engage in comparison, whereas those who do not know the source bypass the whole issue of re-performance, somewhat missing the point. Cochrane performed to a list, which she frequently consulted, reducing each source to one or two dominant gestures, eg spraying perfume on her hands (Fig 3) and shaking hands with the audience (Fig 4).

Cochrane valued the fleeting and the frivolously personal, reducing it to a casual joke or an in-joke. Her performance engaged, entertained, relaxed and amused her audience. (Fig 5)

I know of cases – Jan Swidzinski‘s elegant This is the end/ this is the beginning, This is life/ this is art comes to mind – when one gesture performance had not flattened the ideas and aesthetic experience involved.

Irene Loughlin addressed the instrumental values of art by constructing heavily coded narrative with no flair for calculated understatement. After a brief verbal introduction she appeared carrying a large black toy dog on her back, letting it fall on the floor, later suspending it from the ceiling (Fig 7).

Free of her burden, she put on seven different tartan skirts over her clothes and a pair of tartan trousers. Skirts as sleeves, and as a collar, completed the dressing-up episode. (Fig 6)

The interactions with stuffed dogs (three in all) formed the rest. They acted also as containers, one for salt (Fig 8) the other for white liquid (Fig 9).

Loughlin caught some salt into her cupped hands, some of the liquid into her mouth. A plastic spout positioned in the toy dog’s loins uncannily morphed into a penis discharging liquid into her open mouth and over her clothes. Insecure coding and hurried articulation governed the whole of this performance that ended by her resting on a cushion on the floor. I have not escaped the conclusion that the artist overwhelmed herself by motives, intentions, objects and actions and has not resolved their respective functions.

After that I should be forgiven for welcoming what appeared a considered approach to both objects and actions. Paul Couillard had asked the Bbeyond group:

“to bring an object that you think would be particularly challenging to use in a performance …While I am quite interested in material objects, I am also willing to entertain more open definitions of the term ‘object’ to include such things as accessible local sites, conceptual parameters – as in ‘objectives’ – or other possibilities you might want to suggest.”

During the early 1980s I came across a similar concept when Kevin Atherton surprised an audience in Aachen by performing just two words: “Any Questions?” Couillard, in comparison, had not abandoned the more difficult challenge of having to invent an action triggered by an ‘object’. By placing participatory gestures before and during each episode he both opened the work to others and others to the work. He submitted himself to the Other and exploited the Other in order to translate the words, or the given objects, into a performance. This particular insecurity imbued the process with lightness. Ominously, it made it dependent on the collaboration of the audience, eg he asked some volunteers to lie on the floor (Fig 10).

They obliged silently, evoking for me John Stuart Mill’s warning: “… he who lets the world, or his own portion of it, choose his plan of life for him, has no need of any other faculty than imitation” (On liberty, 1859). Whether Couillard tested his own authority or the generosity of his audience, does not remove this deeper issue. The interactions between the artist and others multiplied, changing direction at each new fragment. A friend e-mailed Couillard a task to have scars “written” on his skin.

(Fig 11) He stripped to his underwear and invited volunteers to place “a scar” by “writing” on his skin. The whole became a sign of the informal, light experiment, his relaxed attitude induced harmonious co-operation between a ‘leader’ and ‘followers’. In a world without conflict the objects become transparent. The personal calmly morphed into the public, the verbal into tactile and visual. Nevertheless, something undesirable lurked in the shadows of the desirables. (Fig 12)

The authority of the artist’s persona led others to perform his requests without resistance, requests always issued politely, and always followed by a thank you. How can trust of a leader be so complete? Why do people prefer to be led? Why do they suspend questioning? At this stage I can come up with a sketchy answer: to refute an offer guaranteed by an authority (in a given field) means losing an association with some value, or values, a subject wishes to posses, while doubting his/ her ownership of it/ them.

Such an authority can be scientific, medical, political, artistic, even criminal, but at its most popular it is the authority of a celebrity. The last category seeped through the intentions of Tanya Mars.

(Fig 13) A focus on appearance, on treasured cultural clichés, in this case the trinity of ‘shamrock-whiskey-potato’, allowed surface participation, drinking the shots of offered alcohol, and passing through the performance. The performer felt clearly comfortable in her chosen role, which she defined by a domestic or a hospitality set-up, her funny oversized green glasses, and green clown shoes she made by wrapping her feet in green tape. (Fig 14)

Watching this and another action evoked a sense of embarrassment – she cannot possibly hold a view that this audience is incapable of critical engagement, can she? Mars revealed her breasts before she taped them over with a green tape matching both her sunglasses and a banner of cut-out shamrock.

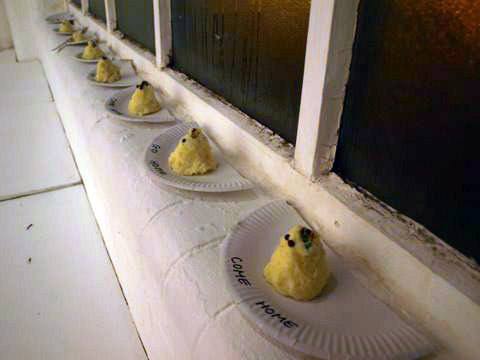

Her soundtrack of Russian names, of names of the countries in Russian, the candles stuck in what looked like mashed potatoes (Fig 15), the bottles of vodka and whiskey were (I am told) intentional codes for her genetic roots. While the intention is a mover, it inevitably becomes subverted both during the performance and through perception. (Fig 16)

Artists easily behave like celebrities. Do many performance art festivals nurture that phenomenon? Do the frequent appearances in different festivals turn participants into celebrities? I have not perceived this until now. Performance festivals facilitate support and intensify development of the art practice, offer valuable exchanges, similarly to festivals of poetry or films. The certain time and space make a festival a preferred venue for an appearance of well-known practitioners and for learning. Increasingly, artists and curators look for ways of avoiding the appearance of stars only. I have been told that they wish to retrieve the risky creativity of earlier performances. On reflection, I saw another aspect of the celebrity phenomenon – the tame audience.

(Fig 17) A kind of believer’s dedication turns the viewers into passive blobs, ever eager to accommodate the performer. This became slightly comical on the video recording of Ed Johnson’s performance. Emerging was a completely surprising meaning. The artist’s authority overruled individual responses. All approached by the artist co-operated willingly and eagerly. Wearing red tights on his head he went around the group of viewers whispering his request. They – without exception – obliged by quickly undoing scarves, buttons, shirts, to allow him to place his fingers on their necks. (Fig 18)

The ease, which governed the interaction, his intrusion into their privacy, inevitably raised issues of loyalty, obedience, trust, and absence of critical doubt. The artist effortlessly removed the threshold between public and private, notably later, by showing his testes, standing on a ladder, trousers at his ankles. (Fig 19)

His final action of stapling plastic bags containing some objects that he used launched the performance into morality tales due to the inscription, a translation of a ‘banner’ in the City Hall and some Orange Halls in Belfast: ‘Pro tanto quid retribuamus.’ (Fig 20)

Taking clothes off and/ or putting clothes on featured in seven out of ten Chaos performances. While changing appearances in all cases, it changed the characters only in the performances by Householder and Boehme.

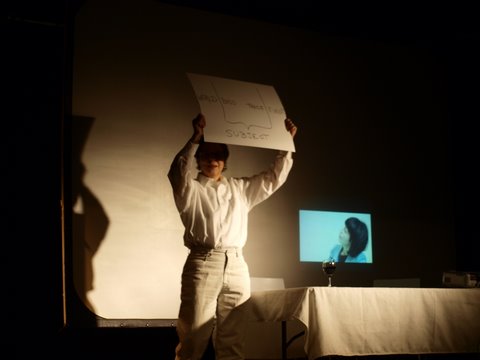

Johanna Householder, wearing glasses and a white shirt, delivered a philosophical lecture on being, existence and trace, mimicking a French accent. (Fig 21)

The glass of red wine and the video of her listening to herself performing forged a symbolic and convincing trinity. Wearing a wig, T-shirt and jacket, she delivered a pop song. (Fig 22)

The f-word appeared in a solo melody, in the chorus, as a refrain and as the core word of the narrative. (Fig 23)

Executed with panache, which cherished humour, this performance hugely satisfied the present audience. (Fig 24)

Even the video trace carries the convincing performances beautifully; Householder controls all details superbly without betraying any effort. (Fig 25)

Hers is a virtuoso performance indeed, elegantly structured and flawlessly delivered. The juxtaposition of esoteric philosophy and a vulgar pop song is grounded in their respective authenticity and energy.

A symmetry between appearance and character also governed a performance by John G Boehme. (Fig 26)

In a blue overall he proceeded to build a wooden platform. He positioned a chair on it. (Fig 27) Moving away, near the wall, he ostentatiously changed into a white shirt, tie and a business suit with a handkerchief in the breast pocket, facing the audience.

Then he filmed the empty chair with his back to the audience. (Fig 28) Facing them once more, he sat on the chair on the built podium as if posing for a photograph, or attending some gathering.

Silently he greeted some, and expressed surprise, or even displeasure, at seeing some others there. While his facial gymnastics coded his attitudes to the imagined or recognised individuals, his hands, relaxed at first on his thighs, developed intermittent spasm, a foreboding of violence or anger. (Fig 29)

With exquisite timing, the third swift change of character received the energy of a madman. He jumped up and proceeded to break the chair and the podium. (Fig 30)

Being a personage calls for appropriate acting, appropriate timing, proper lighting of figure and space and, if used, a good sound system. Both Householder and Boehme delivered on these expectations.

Successfully, Householder and Boehme dipped into skills properly cultivated by theatre or television. The closest ally for these performances I consider tableaux vivants, or the French picturesque gardens of the eighteenth century, so well described in Voltaire’s Candide. Both performers command superb powers of persuasion, escaping effortlessly the obvious pitfalls during the making of knowledge by mimesis. Householder’s critique of pretentious intellectualism and of vulgar celebrities avoids being hijacked by shallow patronising. Her kind of mimesis aims at catharsis instead, with laughter as the cleansing agent. She makes it seductively poisonous and entertaining, akin to the principle of homeopathy. I cherish ‘homeopathic art’ for its economy of means.

Laughter as an instant reward articulated the ‘observing’ phase of Boehme’s pin-striped sit-up comic. However, three parts of the composition surge to an angry critique of some socio-political and economic pact, with fatal betrayal. Both the builder and his product become annihilated, when he climbs up the social ladder. Boehme pairs the self-congratulating narcissism with anger and destruction. The last twist makes the metaphor insecure: the business-suited man projects the product of the man-builder recorded earlier, above the real debris. (Fig 31)

The ensuing proposition that an image saves the past for the future, bypassing the present, stands clear of ambiguity. This cannot be said of the personages: is it just one man going through three stages of man, or are they two men in a hierarchical relationship? Depending on the answer, the meaning could be grounded either in ontology or a class conflict. A loose structure deepens the subversion.

Flexible fluent connections are a matter of concepts, not of information, a principle highlighted by Rachel Echenberg. (Fig 32)

A supremely conceptual performance of collecting Belfast Laugh into a set of glass jars, opening them in synchronicity with a sound track of people laughing, was a well-timed and beautifully crafted transparent structure. The authority of the artist, her cultivated body language, governed the responses. (Fig 33)

At times the audience fell silent and so serious that it evoked a touch of the comical and even absurd. (Fig 34)

Echenberg activated the potential of the impossible, a conviction that imagination creates believable alternatives. This is a poetic performance, fragile for its surrealist root, which in turn imbues it with marvel.

When a particular gives way to a general, something is lost. Judith Price, blindfolded, peeled a block of soap with a potato peeler. For hours. (Fig 35 + 36)

The particulars, like images of animals on the wall, soap powder, and not another powder, or two circular spots of soap powder on each side of the chair she sat on, were neglected until moments before the end. Price reclined down over one of them and with a circular movement of her arms made an impression similar to a snow angel (Fig 37), thus investing it with a kind of significance, that refused to submit its meaning.

The body movement was harmonious, its repetitiveness fresh in comparison to the endless peeling. Rightly or wrongly, I could connect that to the difference between a work and a creative act.

Indeed, predictability lurks behind ideas and creative acts, with no friendly agenda in sight. Sylvette Babin carefully primed the viewer with an installation and her attire. (Fig 38)

Performing in a feminine black top and trousers, she placed a plastic grenade and glass full of seeds from a pomegranate, above an inscription: ‘pomme grenate’. Playfulness surfaced once more, when after some ‘explosions’ Babin gingerly hoisted a white glove over the edge of a table as a surrender sign. In between, she wove into the performance physical endurance, repeatedly stepping on and off a step, faster and faster, or taping over her nostrils and mouth, to make breathing difficult. Bodily, cognitive, neural and social strata of being were touched upon, without the transformation to a meaning. The feminine valorization of labour, effort, of performance, evoked comparison with cultures controlled by men. I just saw a report on Afghanistan’s farmers who replaced opium poppies with pomegranates. Babin’s episodes of ‘terror’ and ‘exhaustion’ work in that context. Maybe it is a coincidence.

At the heart of all these performances is the idea of Self, which at times renders traditional values ineffective. The quest for the authentic Self gets wedged against the gridwork of dominant art practices, on one hand, and inherited social values on the other. The overriding preoccupation with rights, subjectivity and connectivity reveals itself both as assets and as liabilities. (Fig 39)

One of the reasons for this ambivalence is the mismatch between the freedom the artist claims for her or himself, and the unstable audience, at once submissive and questioning. At times, the audience behaved like a congregation of believers. At other times, their response bordered on cynicism. (Fig 40)

This is not unexpected. Moreover, the best idea doesn’t always win, because both its embodiments and perception are a matter of creativity, not of logical, transparently linear thinking. Quotations from another cultural form request that the audience recognise the link. In another cultural context such recognition is not possible. What is then on offer is a loose approximation.

The influences from theatre and television, emergence of re-performance, quotations, responsiveness, and revival of strategies of conceptual and surrealist art were applied to structures of a simple flow-diagram or a complex narrative. Most travelled easily from context to context, as visual art or music habitually do. Few touched greatness. Ideas ranged from philosophy to experience. They included: epistemology, namely how we know the past, traces of the past, of history; relationship to other cultural forms, eg pop culture; the impact of duration on attention, the role of play and imagination as tools of conviction, the impact of masculine physical energy on feeling; and last, but not least, investigations of how life/ subjects/ objects challenge art practice. These investigations could become a beacon of inspiration for the hosting artists when they engage their own creativity.

Slavka Sverakova is a writer on art.