‘El Día de los Muertos – the Day of the Dead’ is a Mexican festival celebrating death and the temporary return of the dead to earth. The belief is that on 1 November, All Saints Day, and 2 November, All Souls Day, the departed return to their family and friends, firstly the children (‘Los Angelitos’), followed the next day by the adults. In the month of October, stalls are set up in Mexican streets selling toy skeletons, wreaths, ‘pan de muerto’ (bread of the dead) sugar skulls and other objects, which the living buy as ‘offrendas de muertos’ (offerings to the dead). These are then placed on altars set up in homes with candles and burning incense in preparation for the return of the dead.

|

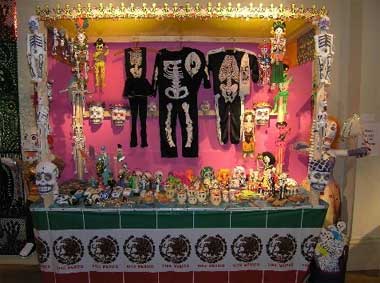

| The Altar, Naughton Gallery; courtesy the author |

Family members also decorate the gravesite of deceased relatives with marigolds, wreaths and artefacts in preparation for the ‘Parade of the Dead’, when they travel to the graveyard and toast the departed. For Mexican people, explained Curator Chloe Sayers in an accompanying lecture, death is part of life and a companion throughout our lives. As in Aztec poetry, dual terms of light and dark, life and death are part of a continuous cycle. But how does a Curator of Mexican art exhibit their ‘curiosities’ in a Western, formalist gallery space? And how can this culturally specific festival be purposefully presented to a Belfast public? To quote Michael Baxandall, “There is no exhibition without construction and therefore – in an extended sense – appropriation." [2]

The curatorial decisions and interpretation of the exhibition at the Naughton Gallery helped overcome stereotypical, Western perceptions of the ‘other’. This was achieved firstly by the relaxed and celebratory atmosphere of the exhibition, with bright colours, objects presented as they would be in a Mexican street, the low-art, ‘kitsch’ appearance of many objects, and the ambient Mexican music playing in the background. Added to this experience, Tiburcio and Carlos Sotento from Metepec were working in the foyer making ‘Arboles de la Vida’ (Trees of Life), and welcoming visitors to contribute their own clay model to the ensemble. Text panels were provided in the entrance foyer to the gallery introducing the socio-historical context, the artists involved, and the Curator of the exhibition. On entering the gallery space, labels were then abandoned and the dancing skeletons took over.

|

| Tree of Life; courtesy the author |

On 2 November, the climax of the festival exhibition and events was the ‘Parade of the Dead’ from Queen’s University campus to Friar’s Bush Graveyard, Belfast’s oldest Christian site and the location of a mass burial after the cholera epidemic in 1832-33. The parade was launched by a visitation from Humberto Spindola’s La Catrina, a ‘female dandy’ who ‘stepped out’ from the mural Sueño de una tarde dominical en Alameda Central by Diego Rivera, to address the living. Her costume, designed by Spindola, was a fabulous silk-paper ensemble, and she paraded herself around the gallery before leading the procession to the graveyard with a brass band, actors from Belfast circus school and members of the public at her heels.

|

| ‘La Catrina’, Performance and costume by Humbero Spindola, Inspired by Diego Rivera and the engravings of José Guadalupe Posada [1852-1923]; courtesy the author |

Once in the graveyard, a large skeleton designed by local artists John Quinn and Dervla McNally danced around the graves, and helpers distributed ‘pan de muertos’ and hot chocolate until, exhausted, the skeleton fell by a graveyard to relax as darkness fell. Participants gradually went on their way after their ritualistic celebration and live to tell the tale. But what really happened? Did the dead really visit the living? And what did they make of us all if they did? In Ireland, where ‘dancing on somebody’s grave’ has far from happy connotations, where are the boundaries between cultures to be located?

|

| I do; courtesy the author |

Some of these issues were addressed by the display of the accompanying Local Souls exhibition in the Visitor’s Centre at Queen’s, where altars to deceased local heroes were created by Clare Leeman with many contributions from an interested public. However, in relation to the exhibition and performance in the Naughton Gallery, certain key critical terms arise. For example, in discussing the ‘aestheticisation’ involved in the gallery display, one student pointed out how the pieces “…will be viewed as art and will be susceptible to the prejudices of people who regard indigenous art forms as that of primitive and of lesser value," [3] and another student pointed out how, “…’Haunting’ the discourse on ethnic art, and presenting itself on close examination in the Day of the Dead, is the dichotomy between ‘fine art’ and ‘craft’." [4]

|

| Grave site, Friar’s Bush Graveyard – ‘The Belfast Bap’; courtesy the author |

These questions were addressed by Sayers in discussion with the group, when she revealed how below the surface of the exhibition were indeed symptoms of globalisation, including the disappearance of tangible heritage in the city of Mexico, and the cross-fertilisation between the festival of Halloween and ‘El Día de los Muertos.’ Furthermore, in terms of ‘commoditisation’, the market for the work of popular artists such as the Linares and Sotento is moving increasingly to American collectors.

Whatever the ethics and politics involved, the Naughton Gallery has fulfilled its mission statement to “..enhance the Queen’s experience." Whether souls returned to Queen’s on 2 November or not we will never know. What will remain, however, is a resonance in the soul of the community at Queen’s.

|

| The Market Stall, Naughton Gallery; courtesy the author |