Janet Mullarney, Model Arts Centre, Sligo, November – December 1996; + tour

Review by Gemma Tipton

Janet Mullarney’s exhibition at the Model Arts Centre took me back. Back to the time when I was in school, learning how to ‘be a grown up’, and how to leave behind the world of monsters (both kindly and scary), and forget imaginary friends. But what is sane and what is normal? Can you be strong-minded, as well as unstable? Who gets to make the definitions, and who gets to choose? We are taught to ignore what is on the edges of our minds, and keep to the mental straight and narrow. The result is that the ‘other’ is relegated to the realm of nightmares and unbidden, unnameable images. This is the stuff of Mullarney’s work, sketched onto the gallery walls, and made concrete in sculptures of wood, clay, wire and the detritus of found objects.

Humans, animals and birds share the space, carved in a manner that suggests both the tribal and totemic, but also something newer, more modern. Something that finds its fullest resonances in this post-psychoanalytic age. The images take you to those places in your mind pushed to the edge of dreaming, the corners of consciousness. Contained Disequilibrium is a collection of little containers. Some are wooden boxes, some raffia baskets, each one different from its fellows. They are held on platforms, at various heights, on rough wooden poles. A little village rising up, out of the mire. They look simultaneously fragile and solid. Tentatively opening each: people, penises and papers are to be found. Small animal and sexual discoveries that draw you in. Sometimes you have to reach up on tip-toes to see inside, sometimes lean down. You see a small doll on a bed, a book with nailed down pages, a vacant space, a strange animal. The first box is opened a little anxiously, but the last with positive anticipation. These images are neither frightening or alarming. There is a comfort to be found in being confronted with your hidden fears. You can see them, touch them, come to terms with them. It is a liberation. Now where did I put that neurosis?

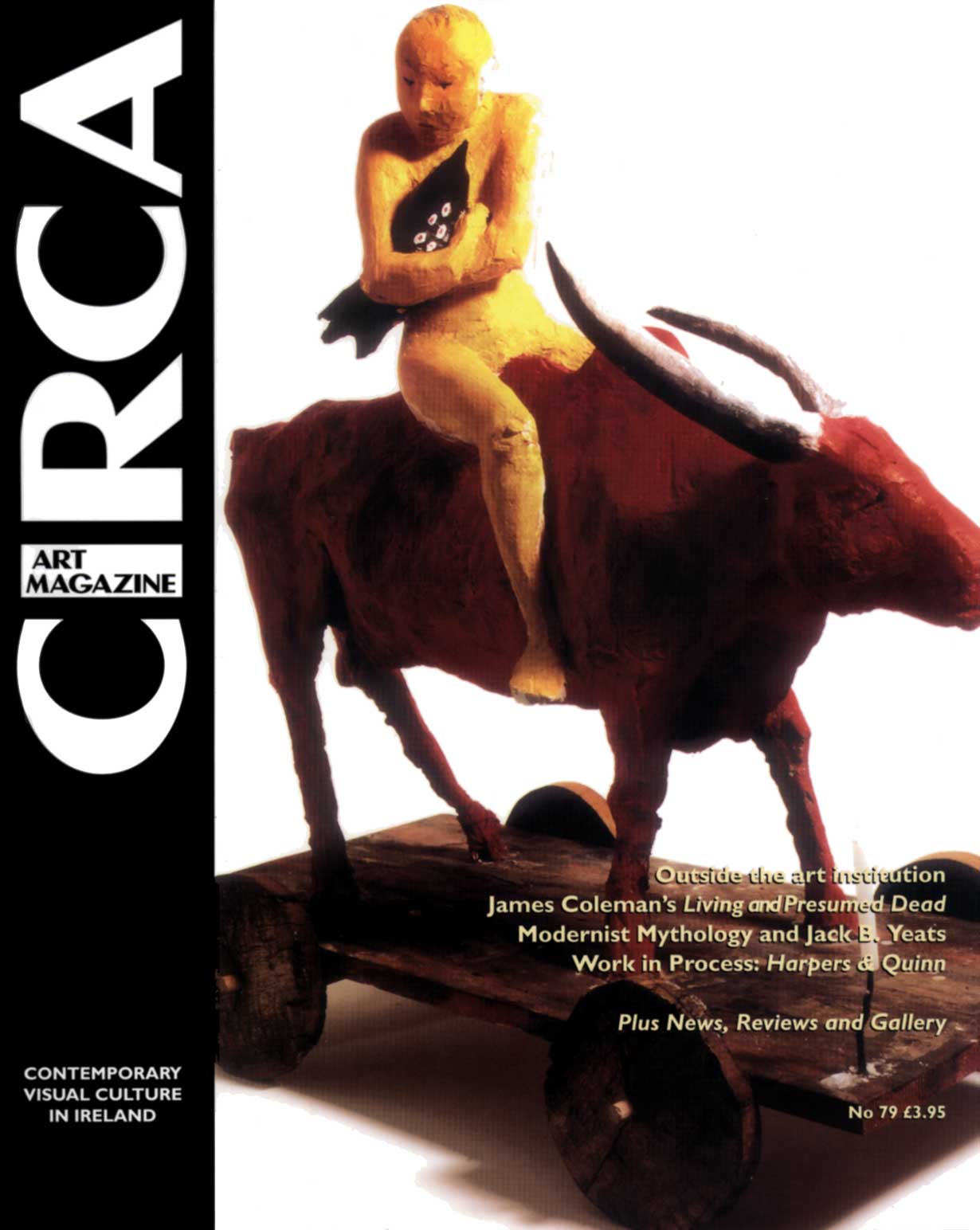

Aftermath shows it one way: a blue female figure lies on a (stained) white mattress, in the sated embrace of a big hot red bullock – horns and all. Sexual guilt, hidden desires and the animality of the act are made real and life size. But no longer something to avoid. It is up to you to decide if the beast is your partner, or lurks within yourself, but the figures sleep peacefully together.

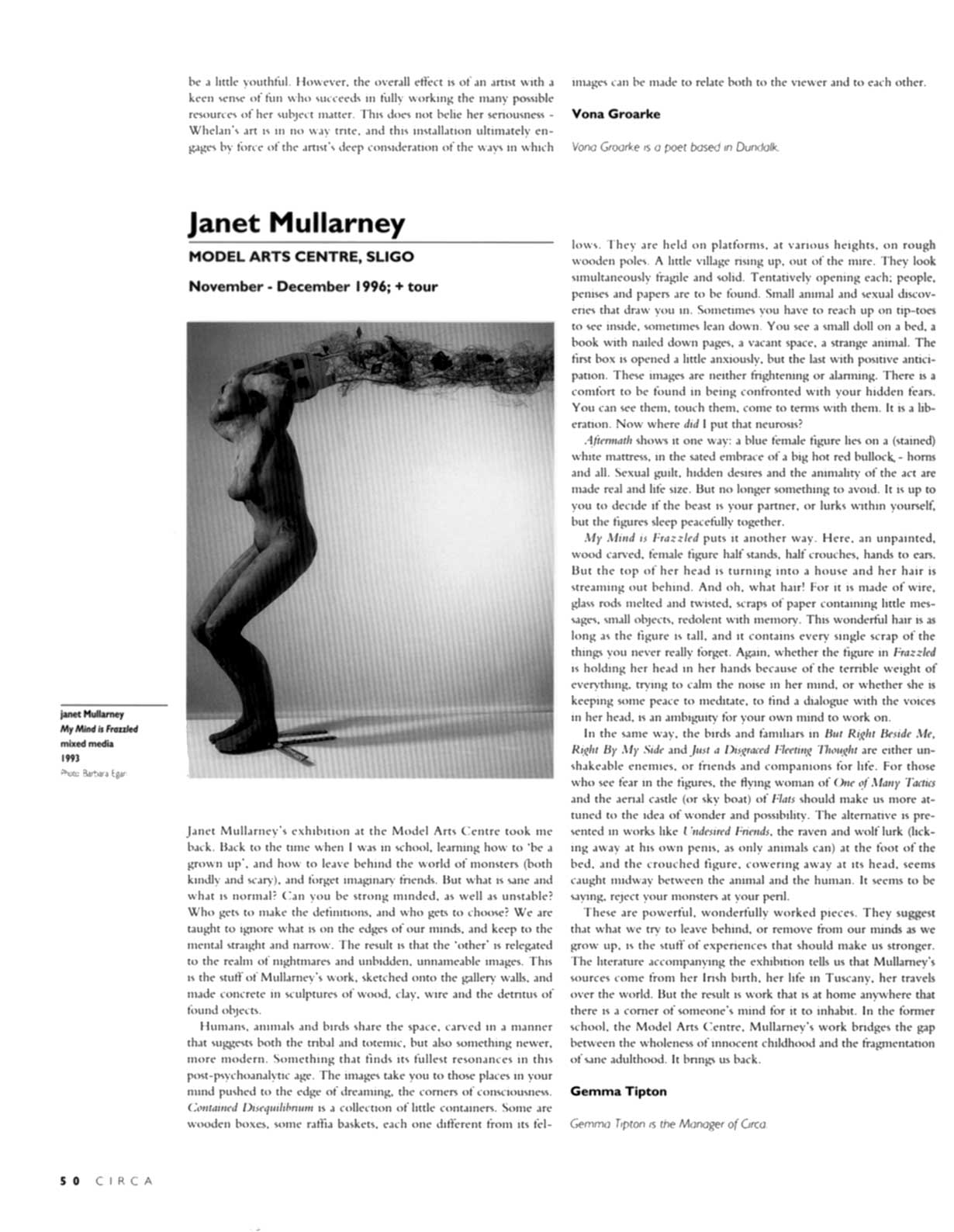

My Mind is Frazzled puts it another way. Here, an unpainted, wood carved, female figure half stands, half crouches, hands to ears. But the top of her head is turning into a house and her hair is streaming out behind. And oh, what hair! For it is made of wire, glass rods melted and twisted, scraps of paper containing little messages, small objects, redolent with meaning. This wonderful hair is as long as the figure tall, and it contains every single scrap of the things you never really forgot. Again, whether the figure in Frazzled is holding her head in her hands because of the terrible weight of everything, trying to calm the noise in her mind, or whether she is keeping some peace to meditate, to find a dialogue with the voices in her head, is an ambiguity for your own mind to work on.

In the same way, the birds and familiars in But Right Beside Me, Right Beside Me and Just a Disgraced Fleeting Thought are either unshakeable enemies, or friends and companions for life. For those who see fear in the figures, the flying woman of One of Many Tactics and the aerial castle (or sky boat) of Flats should make us more attuned to the idea of wonder and possibility. The alternative is presented in works like Undesired Friends; the raven and wolf lurk (licking away at his own penis, as only animals can) at the foot of the bed, and the crouched figure, cowering away at its head, seems caught midway between the animal and the human. It seems to be saying, reject your monsters at your peril.

These are powerful, wonderfully worked pieces. They suggest that what we try to leave behind, or remove from our minds as we grow up, is the stuff of experiences that should make us stronger. The literature accompanying the exhibition tells us that Mullarney’s sources come from her Irish birth, her life in Tuscany, her travels over the world. But the result is work that is at home anywhere that there is a corner of someone’s mind for it to inhabit. In the former school, the Model Arts Centre, Mullarney’s work bridges the gap between the wholeness of innocent childhood and the fragmentation of sane adulthood. It brings us back.

Gemma Tipton

Gemma Tipton is the Manager of Circa.

____

This article appeared in Circa Art Magazine issue 79, spring 1997, p. 50