Take it to the limit: Bernard Smyth at Draoícht, Blanchardstown, July/August 2002

Tension : stretching or being stretched; mental strain or excitement; strained state; effect by forces pulling against each other; electromotive force.

Bernard Smyth’s recent show at the Draíocht centre in Blanchardstown, Dublin, has bothered me since I saw it. This exhibition cannot be pinned down, defined or succinctly categorized into one particular genre. In fact, Smyth’s work creates a complex and intriguing way of keeping the audience guessing at and searching for that all-important punchline, climax or conclusion. The exhibition reflects Smyth’s practice, which on the surface could be read as forming disparate and fractured narratives. The mixed media of video, photographs and form sculpture all create varying levels of tensions. A clear trajectory is formed from the sublimity exemplified by The Stetson, 2002 (a photograph in which the outline of a Stetson hat is picked out in the night sky by a constellation of tiny stars) and Space, 2002 (a photograph and form sculpture of a panoramic expanse of night sky) to the more tense atmospheres prevalent in the video pieces First Shot, 2002 and A Short Introduction, 2002 .

|

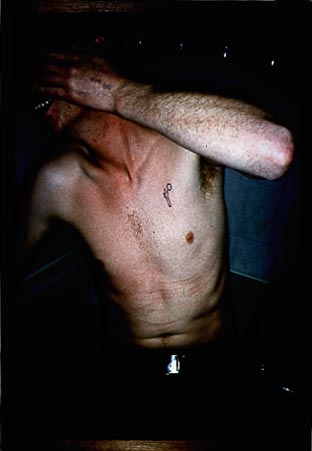

Bernard Smyth: Portrait, 2002, lambda print; courtesy the artist |

The main character and primary subject matter of much of the work is Smyth himself. With a narrative most of us can relate to Smyth portrays himself as a postmodern urban cowboy with underlying sardonic tones. He appears in varying guises – in the photographs Tattoo, 2002 with its twisting torso bearing a small tattoed cactus, an arm hiding his laughing face; Portrait, 2002, a close-up only partially covered by a hoodie; Smoking, 2001, diffused with a warm golden light as a sarcastic Smyth smokes to the Smyth that appears on screen in the shooting range of the video pieces. In these two video pieces, which are separate and distinct though edited to appear as one, we observe the ritual of Smyth loading, shooting, reacting, reloading, and shooting again. In First Shot, 2002, we are witness to Smyth’s reaction to the initial gunshot (literally his ‘first shot’) as his primary instinct is to turn in a split second and duck away from the shot he’s just taken. In A Short Introduction, 2002, subsequent shots are observed casually, calmly and the magazine refilled nonchalantly. Both document the performance and ritual.

Smyth’s video work is reminiscent of the performances of Danish artist Peter Land who is renowned for his inconclusive work. Both artists portray the protaganist as the anti-hero and favor stark sets. Similarities can also be seen in the subject matter – Land dancing naked and drunk to pop music or falling off a chair, Smyth smoking while tap-dancing. However Smyth’s work has something Land’s does not – an almost unbearable tension. Forming a common thread with earlier performances of Smyth’s such as Tap Dancing Smoker, 2001, and World Record, 1999, I find myself amused, then irritated, finally frustrated. This frustration highlights the inability to effect any significant change either in our immediate surroundings or in a wider context. As with Land, we ask but what is the point? what is the point of balancing endlessly on the back legs of a chair? what is the point of tap dancing while smoking, or shooting a gun relentlessly over and over again? Perhaps in the face of our inability to effect change these are the only things we can ascribe meaning to – or that in doing so we gain a little control or significance.

|

Bernard Smyth: Tattoo, 2002, lambda print; courtesy the artist |

The form sculpture Space, 2002, brings an atmospheric tension to the installation. A photograph of panoramic proportions, it hangs the entire length of one wall of the gallery, stretching away into the distance and curving in the middle of the work in towards the centre of the space. Away from the installation and in my mind’s eye this piece takes on sinister proportions. When I look at a slide of the work later I am surprised by how tranquil and unobtrusive the curve is. It is a minimalist work, almost a blank canvas but with the kind of depth of color you might get in, say, Anish Kappoor’s stark and stripped-back minimalist work Untitled, 1990, where the pigment is applied so thickly to form a velvety surface. The curve of Space, 2002, reaches out to pull you in, to immerse you in the vast panoramic expanse of dusky or predawn sky.

There are also parallels and references to Richard Billingham in that the work records something ‘extraordinary’ by documenting something ordinary. It questions society at present, where our lived realities are on show in full tecnicolour close-up. The concept of Big Brother has now become a brand in itself – a reality where the most mundane and ordinary events in people’s lives are documented and our insatiable appetites for such are fed. It is a fact of life that observation by other people and surveillance by machines is almost constant. We are regularly monitored, tracked and followed for amusement, entertainment, or marketing purposes or to be placed in some demographic or other. In Smyth’s work we observe him observing himself. He is under surveillance by himself, the prime suspect in his own story and the investigation has an air of suspicion about it.

|

Bernard Smyth: Smoking, 2002, C-type print; courtesy the artist |

Smyth’s work highlights these and other issues but maintains a sense of dry laconic humor and this combination is what makes it significant and interesting work. However, certain questions remain unresolved and inconclusive and it is that which bothers. What then is the final punchline? Is there one? Or is it simply that Smyth is taking us to the limit, testing our concentration and attention as viewers and observers. In a society where everything is speeding up, Smyth’s time-based rituals demand that we slow down. They force us to observe and immerse ourselves rather than allow everything wash over us superficially. Ultimately Smyth tries our patience, concentration and attention. In return he offers us an experience where time is of the essence and tension, while at times unbearable, serves as a mechanism to show us the beautiful detail to be found in the ordinary and seemingly inconsequential.

Alexa Coyne is a writer and a freelance project manager of contemporary art projects. She currently works at IMMA and City Arts Centre, Dublin.