|

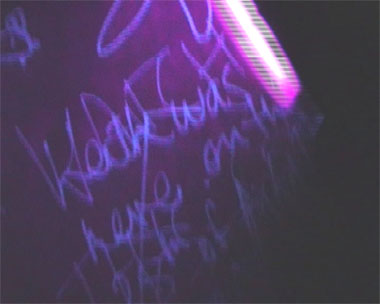

| Acitore Zoyhaus Artezione: Public registry: births deaths & marriages (detail); courtesy the artist |

Curated by Siobhán Mullen and Kerry Plummer, Flow presented work from six women artists. More than 550 visitors saw their art during the nine days, an unexpectedly encouraging statistic for contemporary lens-based art in Belfast. I went to see it during the last afternoon, noticing, with undiluted joy, a nonstop coming and going of people who do not belong to the usual art crowd.

Acitore Zoyhaus Artezione may be known to some readers from her prize-winning submission to Claremorris Open 2002, or the Ormeau Baths Gallery’s Perspective 2004, as an author of experimental films, projections over skylines, or labels on the pavements.

For Flow she intended having a collaborative installation. Artezione invited the audience to write on the walls of her site responses to the title of the installation, Public registry: births, deaths & marriages.

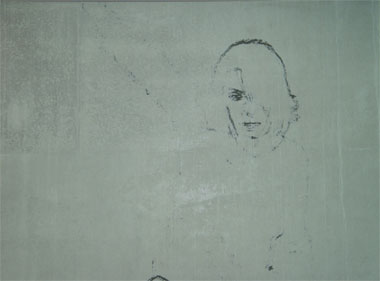

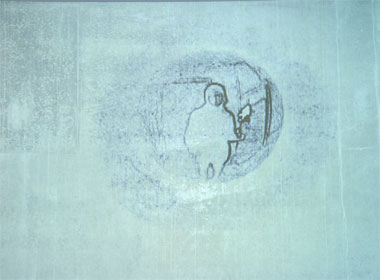

Her focus on words was highlighted by two visual strategies that appeared to have a disabling, or at least hiding function: the responses written on the wall were not visible unless a special ultraviolet light was used. And on the narrowest wall above the wide entrance Artezione projected images of volcanic landscapes, parts of each image erased, or overwhelmed, by a curious bright, torch-like light.

|

| Acitore Zoyhaus Artezione: Public registry: births deaths & marriages (detail); courtesy the artist |

While she intended to obtain “a collective narrative" that “may offer an insight into cultural meta-programming" through verbal responses to specific words, Artezione chose a visual configuration that was a partial denial of its collective impact, promoting instead the individual and private encounter. Artezione had full control of the configuration, whereas she could not control what the visitors might write. And indeed many wrote whatever they pleased, most of it irrelevant to her intentions and the title of the work. The ensuing paradoxes did not weaken any of the layers of the work; instead they forged a situation in which a central item turned into an irrelevant one and vice versa.

Amazingly, the colours of the projected landscapes and the intriguing elliptic presence of the marks on the walls held the work together. They formed the frame for the disruptive randomness of the rest, randomness warmed up by the willingness of the visitors to participate.

|

| Ellika Sjöstrand: Domestic (detail); courtesy the artist |

Ellika Sjöstrand made a short animation of black-and-white linear drawings of a female, who keeps moving and turning from the left to right and who falls out of the last frame – but not before piercing whoever was looking with a direct gaze from her right eye. After the woman leaves the scene, a man appears with a sparkling firework in his right hand, his back turned towards us.

The artist’s intention of presenting the main characters as not able to participate in everyday life outside their front door could be applied to the frames where the man stands at a closed door, but I failed to make that connection to the female character. Instead, I marvelled at the patient work, with each frame progressing from mundane repetition to a split-second revelation of the female as living – just before the fall. I wished to prolong that moment. Later, I came to think of it as a metaphor for the life force, penetrating, powerful and short, like a stroke of lightning.

The video was called Domestic; the two characters were not that, at least while I was looking.

|

| Ellika Sjöstrand: Domestic (detail); courtesy the artis |

Nina Pelletier presented another animation of black-and-white drawings, this time vaguely based on Rapunzel, a fairy-tale by the Grimm brothers. That’s like a fairy-tale focused on waiting: the princess is waiting for her prince or for some change. The passing of the time is evoked right at the beginning by the speed of the princess’s hair growing alongside her body, down to the floor, out of the room. Images are interspersed sparsely with occasional sentences, questions and dialogues, such as “I am a prince and I’ll wake you up with a kiss." Rapunzel answers: “But I prefer women," to which the prince responds, “I nearly forgot – I am a woman, sweety."

On a small monitor the words were easily ignored, and thus I responded to the nonverbal element, which I found cultivated and witty. For example, the introduction of cantilevered stairs with no walls and visible support added to the humour and lightness of the work without detracting from the convincing lie I was watching. Another smile-inducing, beautiful moment occurs towards the end, when the protagonists turn 180 degrees from frame to frame, speed adding humour and delight.

The original intention to focus on ‘waiting’ ceased to matter. It was the inventiveness of the drawing and the disciplined work with frames that made the difference.

|

| Nina Pelletier: Like a Fairy Tale (detail); courtesy the artist |

|

| Nina Pelletier: Like a Fairy Tale (detail); courtesy the artist |

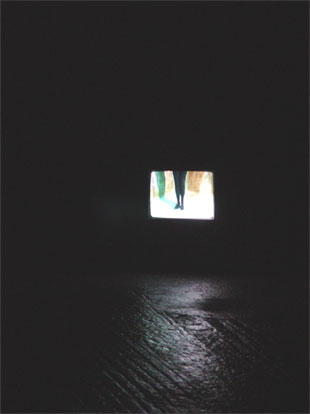

Fiona Larkin ‘s two monitors in opposite corners, as if looking at each other, presented the legs of the dancer of an Irish jig, the same professional dancer, filmed from two different angles. As a result the anatomy looked different, thus providing two dancers. It was a departure from the objective truth, a very worthwhile one.

The monitors were placed in the concrete chamber of the weir where the dancer had performed and where Larkin recorded the images and sound. The sound was very strong, echoing, distorting itself, attacking one’s hearing, domineering.

The two images differed in a number of salient points: on the right-hand side, the dancer’s legs were here and there joined by a sliver of red skirt, or fingers of one hand or the other. Her rhythm was based on accomplished musical phrases, energetically delivered as if in anger or as a very sharp exchange. Each phrase had a clear closure.

At that point, the ‘other dancer’ started dancing, and when she finished, the first one took over again. They never danced at the same time, nor was there a reflective pause. The acuity of observation given to each dancer precluded such reflection and facilitated a swift, continuous loop. The exchange was superbly synchronised.

Although in the real world there was one person only, the art convincingly forged two individuals, each of her own physique and point of view. Without doubt, the two were arguing; it was not just a dance competition. This much was translated into the ‘closures’, by which I mean the pose in which each stopped. The legs literally created a ‘sharp point’ or a blunt ‘wall’. The sheer dancing ability, the heightened technical skill and discipline, prevented me from identifying with either closure, be it aggressive or blocking out.

The video’s title, Everybody is out of step, allows me either to be out of step as well, i.e. to belong, or not to be out of step, i.e. to be alone. This choice makes the work existential, while the Irish dance (the trait of national identity) makes it political – at least in this region.

On both ethical and professional levels the video is successful and beautiful to watch.

|

| Fiona Larkin: Everybody is out of Step , installation shot; courtesy the artist |

|

| Fiona Larkin: Everybody is out of Step (detail); courtesy the artist |

|

| Fiona Larkin: Everybody is out of Step (detail); courtesy the artist |

Siobhán Mullen presented two videos titled Spectacle (the loss of desire) and Singing kettle. Through wall-size muslin sheets the smaller central image lifted Spectacle up above my head. Its pink tones disoriented me until I registered an eyelid – and recognised some reflections in what I thought was jelly. It was a knife. Watching, I oscillated between knowing and not knowing what I was looking at, yet a flow of stable feeling I could not escape from enveloped me. Moreover, the feeling refused to be named. On reading the title, I reflected on the utter absence of desire – for anything, actually. The materials, the motive, the relentlessly slow rhythm, the pink colours all joined forces to forge femininity of some kind, almost like girlie play with dolls, an archetype I regret knowing.

If the video wanted to disturb, it succeeded, while pretending to be sickeningly sweet.

|

| Siobhán Mullen: Spectacle (the loss of desire) (detail); courtesy the artist |

|

| Siobhán Mullen: Spectacle (the loss of desire) (detail); courtesy the artist |

Blue and pale-ochre tones transformed the corner of a concrete room into an underwater universe, as it was, in real terms, under water already. On the right in another dark corner a kettle produced steam and whistled…or not? Singing kettle was easily the most beautiful of images. In the video, a pillar of a bridge stood guard above, and it was reflected in the river that reflected also the sky, the light, the breeze and the starlings that noisily settled under the bridge. I enjoyed the video as a celebration of water, an element covering the greater part of the surface of the Earth, an element which we are made of too. Water has been photographed by scientists in recent experiments, one of which associated with what I was looking at in a pertinent manner. Dr Masaru Emoto photographed molecules of water at low temperature and observed that contaminated water produced no crystals, only wild shapes, while clean spring water formed beautiful patterns. (see http://www.adhikara.com/water.html ). Emoto’s connection between order and purity (original natural state) resonates well with Mullen’s power to displace the anthropocentric by synchronicity between the observer and the observed.

Mullen mentioned to me her lengthy observation of the river and of the starlings as the source for Singing kettle. It brought a depth and significance rarely obtained otherwise.

|

| Siobhán Mullen: Singing kettle (detail); courtesy the artist |

Kerry Plummer is a storyteller par excellence. She holds the camera so very still, and for the whole length of the mis-en-scène. This heightens any movement inside the frame; moreover, duration allows the arbitrary to slip into something necessary. Also, the distance from the moving object creates alternately a sense of relaxed safety or terrorizing threat. Consequently, an observed fragment of a real event animates itself into a feeling which is then the only clue by which to anticipate what might follow. And it does not. The use of elliptic editing as well as of repetition calls for mastery of both timing and duration; these were present.

|

| Kerry Plummer: Impending (detail); courtesy the artist |

The projected image covered the whole wall, making the objects, such as cars, buildings, roads, etc. a bit under the life-size, yet large enough to form an illusion of my space and its space being continuous. That suggestive element is important for the story, which ends with a train traveling parallel to the picture plane, without any clear barrier between it and the viewer. The resulting feeling of some danger comes as no surprise; what is surprising is that no accident occurs. Such oscillation between two opposite possibilities would be unsettling, had it not been for the calm phrasing of the images.

Throughout, juxtaposed over the main story lines, two eyes appear, wide apart. Eyes of a child watching … Plummer’s son Harry.

Impending started with a painterly image of the train track dominated by a church building. Views of a road, a street, a crossroad, a railway crossing provided a build-up from the early and eerie silence to the noises of civilisation and the threat of a powerful machine. All together, it worked as a metaphor for growing up and parenting. Plummer wrote in support of the video:

Impending aims to recreate

That feeling of anticipation

Of the unknown

Waiting to grow up and

Your life to start …

Not knowing what to expect

But fearless

Waiting for your child to

Grow up, fearful …

|

| Kerry Plummer: Impending (detail); courtesy the artist |

At the end: a man came in saying that another man he met outside told him that there was a good exhibition down here. I agree.

Slavka Sverakova is a freelance writer on visual art.