In his ongoing project, Self-Portrait as a Building, Manders’ core intention has been to map out and construct for himself a double, or parallel, existence by bringing to life a body of fictional scenarios. The disjuncture between these scenarios and our own is exaggerated by Manders reduction of many of them to eighty-eight percent life size, and his demand made upon the audience to treat fiction as real whilst maintaining its surreal status.

|

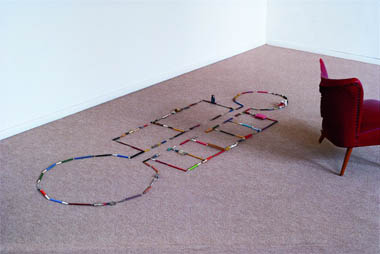

| Mark Manders: Inhabited for a survey, 1986, writing materials, erasers, painting tools, scissors, Dimensions variable; courtesy Howard and Donna Stone, promised gift to the Art Institute of Chicago / Irish Museum of Modern Art |

In the first room of the show at IMMA, Manders takes this project literally, presenting Inhabited for a survey (1986) as a provisional, improvised ground plan constructed of broken pencils, crayons, screwdrivers, sponges and other artistic paraphernalia. The plan has the symmetry of a human figure, but seeing that it also evokes the layout of the Kilmainham* corridors it suggests, moreover, that reciprocation between institutions, history and innovation which is central to creative fiction. Manders’ double waits patiently, inhabiting and adapting this plan as both a model and a means.

True to the rich literary tradition of the doppelgänger, the results of Manders’ project are disquieting and perverse, and offer a nuanced play on the intersection of fictive, broken personages with the artist and audience who reanimate them. In Isolated bathroom (2003), three figures lie in a prostrate stupor, armless, wrapped in polythene, with their heads propped up on clay bricks. Their androgynous features display little other than what might be resignation in the face of the passage of time marked out by the dripping of a tap and the slow reclamation of clay by water. The water drips from a ballpoint pen into the bath, and as it does so the pen makes small movements suggestive of automatic writing. Like Manders’ work as a whole, these sentences of nonsense would register the quasi-geological forces at play, but would never quite make them legible. Instead, nonsense allows for a profusion of unpredictable, poetic associations.

|

| Mark Manders: Isolated bathroom, 2003, iron bathtub with wooden tap, water pump, thin plastic sheeting, painted aluminium, ceramic, wigs, 450 x 300 x 75 cm; courtesy Sammlung Goetz, Munich / Irish Museum of Modern Art |

The scene is expectant yet solemn, like that of an indefinite crime. This atmosphere is enhanced by the tension between the processes of dissolution and preservation at work: just as polythene suffocates, becomes a murder weapon, so it preserves, keeping the moisture in the clay, preventing cracks, and embalming the figures in preparation for some future removal. The dripping tap has tortuous connotations, of course, but here it is reminiscent more of a secret system of catacombs or shadowy ginnels. The small actions of water can be tranquil but they are persistent. Bodies and personalities are soft as the earth; soluble but therefore vulnerable to processes which exceed them. Perhaps reflecting on the simple fact that “reality does not usually coincide with our anticipation of it" (Borges), the artist anticipates the gruesome circumstances of these processes by playing them out with three golems and, putting his faith in this ‘weak magic’, trusting that something similar will not happen to him.

Elsewhere, another golem waits patiently with one leg suspended on an L-frame. Its invalid condition is animated by the history of its surroundings. And again, there is a whole hierarchy of weights and counterweights precariously balanced against one another: one is made aware of the fragile suspension of disbelief required to play the game of fiction, for one knows that were this balance at any moment to collapse this whole ambiguous, sophisticated metaphor would become just a collection of inert objects again.

One presses past Cupboard (2004) – a towering stack of Irish daily newspapers in a recess between rooms – without dithering. The accumulated weight of something so insubstantial as newsprint, so close by and so tall, is unexpectedly disquieting, and does not encourage prolonged contemplation; indeed, it purposefully thwarts the desire for legiblity by presenting only fragments of script. In passing, though, one might consider the gallery as a storage space for unwanted, obsolete objects; or, perhaps, the press as something to be avoided, even as something with its own distinct smell…

Manders casts shadows. In Reduced summer garden night scene (2002), he brings these shadows into the light of day to be scrutinised, presenting a cruel and naked terrain vague to be viewed safely from behind transparent screens. The hedge-back detritus – bottles, coffee cups, candles – of this ‘garden’ is reconstituted as a system of trip-wire booby-traps. A bisected moggy is the victim of these crude devices: “[a] cat split in two by a thread, a literary device or textual mechanism that serves to cut coherency in half" (Kuzma) – the coherency, that is, of the opaque night that serves as backdrop for these monstrous imaginings. The body of the night is a broken landscape, harsh and barren, fleshless and grotesque, yet with a physiognomy of its own.

Here we come across a recurrent element of Manders’ works: the existence of a ‘night of the world’, before meanings, symbols and languages enter our world. Or more precisely, that the subject, when it seeks to construct for itself a recognisable and stable human ‘architecture’, must first pass through a traumatic, phantasmagoric night of part objects and spectres. It is this ‘excess of subjectivity’, this multiplicity that cannot be reduced, that is unearthed and manipulated by Manders. It would be mistaken, then, to accuse him of being obsessively morbid, or something similar: his macabre humour plays with the night’s remains, and therefore with the uncomfortable core of our humanity.

His brutal, distressed Drawings with vanishing points play with the conditions of perspective as both the cause and the consequence of an individuated, subjective ‘point’. Perspective can be thought of as a disciplinary construction, in the sense that it counteracted man’s natural ‘unruliness’ and that it formed part of the stable architecture of a certain life-world. In contrast, Manders makes it a framework for ‘unruly’ imaginings, whereupon perspective, as a site for the emergence of a fixed point of order, becomes ridiculous, if not simply derelict.

|

| Mark Manders: Parallel occurrence, 2001, painted wood closed and table with aluminium fox, iron chain, locks, keys, rope, aluminium letter, iron block and artist-made newspapers, dimensions variable; courtesy The Art Institute of Chicago, restricted gift of The Buddy Taub Foundation, Jill and Dennis Roach, Directors / Irish Museum of Modern Art |

Parallel occurrence (2001) is Manders’ most elaborate construction in the show and, fittingly, in it converge many of the currents described hitherto. An aluminium fox with a letter in its mouth is made to look like compacted clay, all of which is suspended by a chain over a table perched atop a cupboard. This chain then stretches across the floor in front of the cupboard, where it is held in place by a wooden block. There is text on sheets of paper apparently protecting the upturned table from being marked by the chain, but again, this text is nonsensical and offers no easy point of access to the work. However, whether or not this construction functions as a consistent allegory is beside the point, as it demonstrates most clearly the fantastic illegibility of Manders work. Above all, one is struck by another “disturbingly quizzical [environment] whose precise but unlikely combination of animal, machine and furniture-like elements approaches the surreal" (press release, Isolated Rooms , 2003), but whose palpability does not allow it to remain a mere phantasm. Although Manders does indeed breathe life into objects, as sculptors have always sought to do, this is countered by an equally strong propensity to turn the stuff of life into mere objects.

The structure of the last piece, Small isolated room (2004), is similar to Inhabited for a survey inasmuch as it consists of a basic plan outlined on the floor from everyday objects such as wood, pencils, dice, wool, sponge and others. This plan for a room leads to an opening into a charred torso / landscape, atop which stand two chimneystacks and two emaciated saplings. Whatever the poignancy of the associations that surround Manders’ choice of objects here – whether the torso / landscape encases a factory, a crematorium or a womb – and elsewhere, above all he returns us to the black earth.

TIm Stott is a critic based in Dublin.

*IMMA is located in Kilmainham, Dublin.