Where are the dead cats?

There is an asymmetrical exchange of knowledge and culture between China and the West. As Theodore Huters writes, introducing Wang Hui’s China’s New Order: Society, Politics and Economics in Transition (2003), “it has long been a matter of concern among Chinese of even modest educational attainment that there is far greater attention to and knowledge about the West among ordinary Chinese than there is awareness of China among Westerners." An exhibition of contemporary Chinese art is to be welcomed then, if its representation of Chinese art adds to the awareness of a Western audience.

By all accounts contemporary art in China is flourishing. It has even been claimed by some particularly enthralled contemporary art lovers that China’s current ‘renaissance’ is comparable to the emergence of Western Modernism over a century ago. Whilst this may be a rather tenuous comparison, there can be no doubt that something vital is happening. The strictures set out for a Social Realist style of art following the Cultural Revolution have been gradually relaxed since the early 1990s, allowing for a plethora of work previously unthinkable.

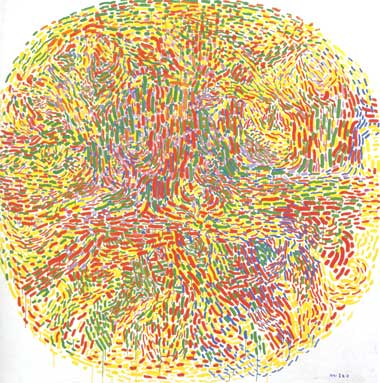

|

| Yu Youhan: Circle Series: Multicolour Circularity Series 91-5, 1991, acrylic on canvas, 200 x 198 cM; courtesy Irish Museum of Modern Art |

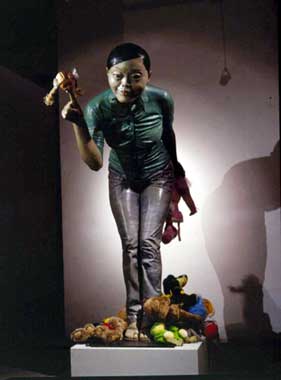

Economically, politically and culturally China is ‘opening up’ to the West, or more precisely, to global capitalism; and the current exhibition at IMMA comes about on the back of the recent establishment of trade links between China and Ireland (the latter serving very much as a bridge between European and American markets, and a low-tax magnet for foreign investment). But China’s dizzying incorporation into global capitalism has given rise to some rapid and less than progressive changes in Chinese society. Not least, the advanced consumerism of urban areas grows apace, surrounded by intense, rural poverty as a result of gross class inequality. All the while, the new capitalist ideology of ‘consumer freedom’ serves to disguise social ills and the increasing commodification of everyday life. Such rampant consumerism and urban growth is the subject matter of much work on display here. However, this is often presented in terms of a simple opposition, which does not acknowledge the structural inextricability of certain forms of artistic practice and capitalism. Looking at Xiang Jing’s Gift, we might say that although the nanny’s offer of cuddly toys might indeed have dark motives, the child still demands and looks to the nanny to provide, and it still enjoys the benefits of its affluent upbringing.

|

| Xiang Jing: Gift, 2002, fibreglass, acrylic and toys, 165 x 55 x 200 cm; courtesy Irish Museum of Modern Art |

For example, the global benefits that some of China’s artists have experienced in recent years have been facilitated by their country’s entrance into the WTO and its adoption of the latterÕs free-trade agenda. At the risk of crude generalisation, one might say that Chinese artists becoming prominent on the Biennale circuit is a direct corollary to the growth of consumerism. In light of this, works such as Yang Zhenzhong’s Let’s Puff seem to overlook the complicity of soi-disant critical artists with their object of criticism, and that whatever ‘critical distance’ these artists might attempt is dependent upon such contradictions.

We are presented with an apparent consensus, consisting of relief that the ‘dark days’ of the Cultural Revolution and its attacks on the bourgeois notion of art as a means of self-expression are over, and a vague optimism that the neoliberalist agenda of the CCP (if only its more unpalatable aspects can be erased) will bring democracy and justice in society, and in the arts, individuality, diversity and global recognition. Upon the evidence of neoliberalism elsewhere, this seems a rather more utopian goal than those of the now discredited Cultural Revolution.

As one enthusiastic artist from Factory 798 (an immense converted factory in the centre of an old Beijing industrial district that has been promoted as an emblem of China’s contemporaneity in art) has recently said: “this place used to be the centre of socialism. Now it’s the centre of modernism and individualism." The Chinese government’s toleration of such centres is fully in keeping with their development of an acceptable global image.

|

| Xue Song: Greet Master, acrylic on canvas, 150x 180 cm; courtesy Irish of Museum of Modern Art |

Modernisation, it seems, is either to be condoned or condemned depending upon which shape it takes. Where it is associated with industrialisation, the drive for efficiency and mass identification, it is to be condemned; where it is associated with individuality and the ‘freedom of choice’, it is to be condoned and encouraged. Modernity, of course, was / is always split between its oppressive and emancipatory potential, but there appears to be a certain amnesia here about how modernity was approached in the activities of the avant-garde: these activities were not a celebration of individuality and humanist ideology but an attack upon these and the social alienation that accompanied them, as well as upon the bourgeois complacency and propriety of art institutions that propagated such notions.

In keeping with the times, the art on display here shows all the marks of postmodern techniques of appropriation, deconstruction and the ‘interrogation’ of historical canons. However, bearing this in mind, one must ask oneself what were the criteria for inclusion in this exhibition. Were works selected that would be in a format familiar to cultivated Western European eyes, i.e. a format that would be recognisably, and indeed properly, ‘postmodern’? If this was the case, then not only does this policy continue to exclude consideration of a world outside a China-West space which nonetheless has a direct impact upon this space, with the result that both China and the West become reified in their images of each other, in direct contradiction to what would be a deconstructive approach, it also excludes much Chinese work perhaps thought to be unsuitable for Western sensibilities. This reification is attested to the paintings of Zhang Jian, which give us the peculiar spectacle of chinoiserie by a Chinese artist.

|

| Zhang Jian: Early Spring, 2003, ink and colour on silk, 210 x 80 cm; courtesy Irish Museum of Modern Art |

Such an approach seems to presuppose that familiar ‘postmodern’ tactics are inherently political, perhaps even radically so, and that they will then permit some kind of authentic artistic expression at last freed from the ideological shackles of Communism. But postmodernism denies such notions as ‘authenticity’, ‘truth’ and ‘progressive politics’ (if not politics tout court ). It is, moreover, the perfect cultural accompaniment to those neoliberal policies supposedly being questioned. In many cases, postmodernism results not in the interrogation of historical and artistic canons in the name of truth and reason but in the “massive subordination of cognitive statements to the finality of the best possible performance" (J-F Lyotard, The Postmodern Condition, 1984). The success of a performance is often dependent upon nothing other than rhetorical power; hence, history itself remains subordinate to power. In such circumstances, the distinction between what is radical and what is reactionary – a difficult decision at the best of times – becomes all but meaningless.

In this climate, where history is either performed, commodified (as witnessed by Hong Hao’s My Things No. 1 [2001-2]), where the raised fist of the Revolution becomes just another object amidst the detritus of consumer identity), or forgotten altogether, there can be no development of a historical consciousness that would build upon the failed aspirations of past generations and not allow a simple repetition of the same dressed differently, so to speak. There is none of Walter Benjamin’s “revolutionary nostalgia," that is, “the power of active remembrance as a ritual summoning and invocation of the traditions of the oppressed in violent constellation with the political present'" (Terry Eagleton. Capitalism, Modernism and Postmodernism, 1985). The latter here might be a radically political response to the pervasive effects of neoliberalism in China, but it would involve the rather unsavoury task of asking why the revolution failed and what part of its content can be revivified. It is perhaps within art that this content can be examined and put to task on many fronts.

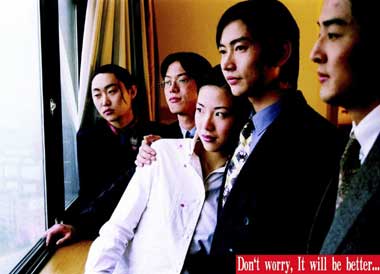

|

| Yang Fu Dong: Don’t worry, It will be better…, 2000, photograph; courtesy Irish Museum of Modern Art |

So, where are the dead cats? There has been much art made in China recently that would test the most ‘liberal’ of cultural relations. For instance, Shanghai artist Xu Zhen videoed himself beating a cat against the floor for forty-five minutes (although he later claimed that the cat was already dead): Sheng Qi cut off one of his fingers and took a photograph of the same hand holding a picture of Mao Zedong; Peng Yu’s six-by-four-metre Curtain (1999) consisted of living lobsters, grass snakes and frogs (all three types of creature being a major part of Chinese cuisine) strung together on a wire frame; works in the exhibition Post Sensibility (Beijing, 1998) made use of human limbs and foetuses; and Zhu Yu’s performance, simply titled Fuck Off (2000), was to involve the eating of aborted foetuses, though it was banned by the Chinese authorities before it could take place.

These are not only shock tactics. After all, ‘outrage’ is a common-enough criterion for Western art for it to be completely meaningless, and shock is perhaps not the intention of most of the above artists, notably Peng Yu, who argues for the raw beauty to be found in her work. These works might be seen as a rejection of the Western tastes and sensibilities that Chinese artists are often required to pander to as a precondition to their entering the international art market. Even if these works are not intended as a straightforward rebellion, they highlight a very real difference between two ethical and aesthetic environments that cannot be wholly erased by its subsumption under the principles of the global art market and exhibition circuit. The absence of this work is echoed in the lack of any serious discussion of the revolutionary legacy and its impact upon Chinese art and thought. Qian Liqun describes Mao Zedong as “a fruit hard to consume, but impossible to discard." The same might be said of some of the Chinese art that is notable here by its absence.

Tim Stott is an art critic living in Dublin.