Dissolving Histories: A Moment in Time

Golden Thread Gallery, 30 November 2017 – 20 January 2018

A Moment in Time is the first of a long-term series of exhibitions titled Dissolving Histories, to be held annually at Belfast’s Golden Thread Gallery. It follows a previous series of twelve shows held between 2004 and 2015, titled Collective Histories of Northern Irish Art. These earlier shows were selected by twelve separate curators with diverse, often opposing, approaches to gathering together art practices with significance to the north – a history which, as the name suggests, aggregates to form a multi-faceted story of northern perspectives, which “understands history,” according to Golden Thread’s Director Peter Richards, “as something that’s fluid.” The Dissolving Histories series will differ in three ways. Each show will be curated collaboratively by Richards and one chosen partner, it will be open to the island of Ireland as a whole and the focus will be on the present and anticipating the future.

The title of the series, Dissolving Histories, is puzzling and a little worrying. Is Richards suggesting that histories can be dissolved, or that they can act as a solvent? Either way, the negative implication of the fluidity of reality is unavoidable. Such a concept is not borne out by this first exhibition, as the historical plays its concrete part in much of the work shown.

A Moment in Time, curated jointly by Peter Richards and Sarah McAvera, shows the work of five young artists early in their careers and it hints at a shift in aesthetic priorities, showing a desire for the kind of skill and artisanship that their preceding generation has largely disregarded. Contemporary considerations fuse with tradition and occasional art historical references. Engaging with much of the work, one finds oneself a little confused as to the relationships between the formal and the conceptual, the latter often consumed by the former.

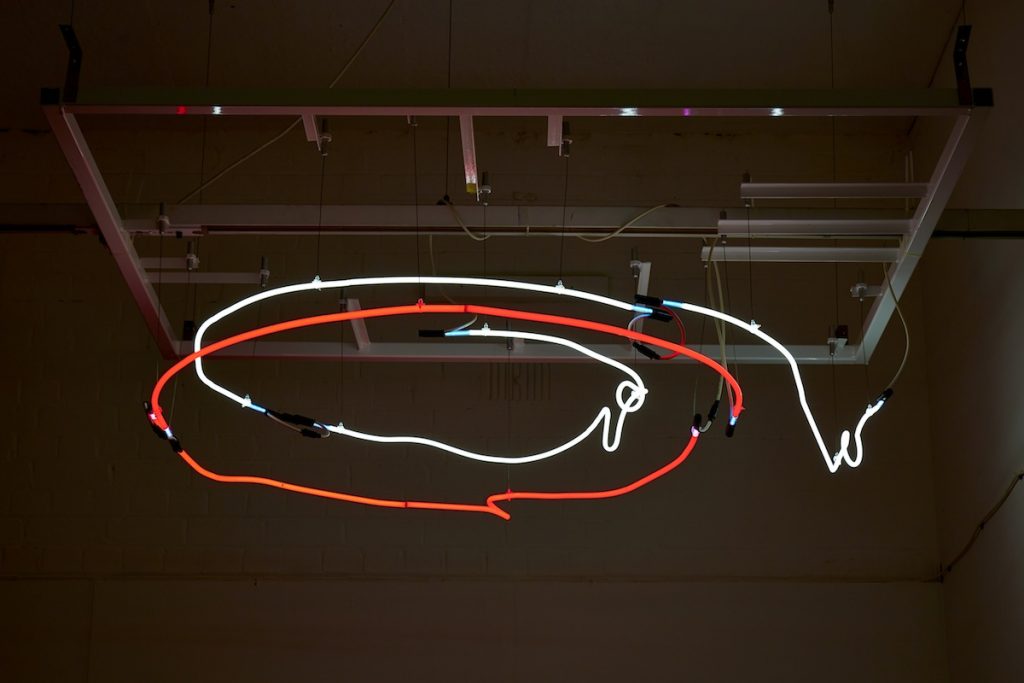

Kevin Killen’s neon sculptures are three-dimensional reconstructions of long-exposure photographs of the movements of a dancer holding lights. They thus portray, through the motion of the human form, snatches of time held in suspension. They bring to mind the photographs of Gjon Mili, especially the famous 1949 light drawings made with Picasso. The fragile curves are held in place in various ways, mostly incorporating laboratory retort stands. In one case, this clinical form of presentation is countered with a stage of white-painted second-hand bricks, strong and supportive but damaged – like a makeshift Carl André. This visual contradiction further references the commercial uses of neon which juxtaposes the pristine appearance of its tubes with the aged ruggedness of the street. Killen adds another contradiction in the deliberate positioning of the work, either on walls or hanging from the ceiling, in defiance of the process of the original dance movement. The direct figurative associations are thus removed from the audience’s engagement with the work.

Erin Hagan has selected her materials according to stark qualitative contrast. The hard angularity of her welded steel and the fluidity of her unspooled wool simultaneously counter and complement each other’s distinct characteristics. In the two steel and wool pieces the zigzagging of the welded lines suggest (like Killen’s neon) dancing forms, but with the spasmodic motion of a drunken disco. In one, the line moves upwards from the floor, resting with a hard horizontal against the wall. The second has two forms intertwining, almost violently, but with a strange elegance. Both have wool falling amorphously from the metal, like bodily fluids released in the vigour and ecstasy of the dance. The third piece consists of two subtly angled verticals, embracing gently now in a slow sway – an affectionate counterpoint to its two companion pieces.

Liam Crichton’s floor-to-ceiling installation is also constructed from welded steel, and gives ghostly evidence of a recently removed gallery wall. The walls, ceiling and floor retain the marks left behind and the original structure is given new form, but subtly twisted and confounding expectations. Jutting perpendicular to this, and cutting into it, is a rectangular frame over which is draped a plaster-soaked swathe of fabric, apparently hastily thrown, but evidently considered and composed, akin to the draperies that define the human form in classical and Renaissance sculpture – consider the “Elgin marbles” or Donatello’s Habakkuk. In an echo of Hagen’s wool, the lower part of the fabric flows like liquid on the floor. This particular reference to the classical has been seen in Crichton’s recent work, which has removed the human element and expanded the drapery to create formalised friezes.

Our first sight of John Rainey’s work is a large, simple rectangular 2×2 pine structure with coloured classical figures on high. Moving round this, we find a staircase, leading us up Mount Olympus to encounter the Gods face to face, but back in time only as far as the postmodern 1980s, surrounded by an elaborate and oversized black-and-white-faux-Ettore-Sottsass-patterned-Haim-Steinbach presentation stage. The seven sculptures are porcelain casts of downloaded and 3-D printed versions of Joseph Nollekens’ Mercury (1783), pastel coloured and altered to give them individual identities – one, for example, has wings for eyes, another is given uncharacteristic body hair, and one other is burdened by its helmet collection. They are reminiscent of contemporary ultra-individualised superheroes as much as ancient gods. The last is recognisable as Hermaphroditus, with the head and breasts of Nollekens’ Venus (1773). S/he is covered with the same Memphis-style pattern as the podium which, like many commercial representations of women, seemingly reduces this feminised manifestation to an adjunct to her surroundings. The process of downloading a scanned extant sculpture and using traditional casting techniques raises anew questions about the transformative nature of the Duchampian readymade. The company responsible for making available the downloadable STL file has made a commodified multiple of a singular artwork, while Rainey subsequently retransforms it into a series of individual sculptures.

The most compelling, and most challenging, work in the show is that of Dorothy Hunter. Her installation consists of a number of autonomous but interrelated pieces. A clay sculpture, based on a decorative stone imperial eagle from the frontage of the Humboldt Forum in Berlin (or rather on a photograph of it), sits on a plinth decorated with a printed red marble kitchen laminate. Because it is modelled on an image, the unseen remains unformed. The raw, unfired clay has cracked over the duration of the show, revealing its armature. Beside this crumbling two-dimensional empire is the resting place of further menacing birds: Hitchcock’s climbing frame is crudely, but accurately, rendered flat against the gallery wall. Accompanying this are out-of-focus promotional videos for the Windell security glass manufacturer. This ironic juxtaposition (impossible to perceive with any clarity) with images of the erroneously-assumed infallibility of empire, brings to the fore the dialectical nature of power struggles throughout history. Leaning against the wall opposite are four sheets of dibond with their protective film still on, its printed arrows pointing up, down, left and right. The implied turning is repeated in a section of the marble laminate of the eagle’s plinth, repeated and rotated, looking now like a small slab of fatty meat. The only hint of image on this dibond is the drawing made by scratching away the film, in a line which repeats the perspective of the Birds frame. Projected onto the piece is a small video illustrating Kelvin-Helmholtz instability in liquid. Hunter’s work is tough to decipher, but the dialectical tension is tangible. The chaotic meets human endeavours to assert authority, in what she has described as “nature co-opted by ideology”.

Such conflicts run throughout the show. The skeletal strengths and the epidermic/visceral fragilities of mortal existence battle it out in the struggle for life’s continuation. Perhaps a strange conclusion to arrive at while engaging with the work of a group of young artists, but the implied sense of danger in this exhibition is disquietingly evident.