This unplublished essay by Declan McGonagle forms the introduction to an exhibition last year in Dundalk, curated by Fiona Mulholland.

The Basement Gallery in Dundalk is literally a series of basement spaces in the Town Hall building in the centre of the town. The spaces are arched with mostly low ceilings and, though well finished, contrast dramatically with the refurbished building above, through which a visitor has to pass to reach the Gallery spaces, which retain the identity of an older reality. These were originally cells from which prisoners were taken to be transported as convicts or to be executed. One space was a death cell, another a priest’s room.

These are haunted spaces therefore – haunted by memories and, for us, imaginings of that history, a history which, for quite a long time in Ireland, gave us a narrative as a people. We were oppressed and poor, cash poor and culture rich, our condition somebody else’s responsibility. This was a simple direct narrative and therefore extremely powerful as an explanation of our condition and informed our self-image for generations if not several centuries. We felt we knew who we were and what our relationship to the world was. We lived in a myth, in the present tense, which connected us directly to the mythic in the distant past. That short circuit is what the rest of the ‘modern’ world saw in Ireland, from the urban version in Joyce’s Dublin to Sean Keating’s rural version in Men [and landscape] of the West. We seemed to believe this story ourselves and for a period wrote it up and packaged it for sale and used it as a mode of commercial and cultural exchange with the modern world. The process hinged on a concoction of innocence, the idea of a place and culture apart from modernity and a narrative of simplicity.

By the mid nineteen nineties the tension between image and reality became unsustainable and, on the back of a new economy, greed became visible and was rewarded. And in the face of a flow of economic migrants we revealed ourselves as actually caring less about the ‘other within’, a role we had virtually patented.

Every level of Irish society has lost any pretence of innocence and it is now impossible to project the ‘simplicity’ which the previous narrative articulated. Being Irish used to be a statement, now it is a question.

In this context it is interesting to see how a generation of artists, linked by attitude as much as age or nationality, are beginning to explore and describe a sense of complexity and complicity within the ‘modern’ world and the sets of relations within which Ireland, and artists, are negotiating a new narrative and new relations in social space. The title of the exhibition, The Space in between, refers directly to this sense of negotiable space while the subtitle, an exhibition of sculpture, knowingly belies the complexities of meaning, material and form which are addressed directly, and with striking confidence, in this project.

In Samson and the Philistines [12 triangles], Noel Brennan literally builds an open space sculpture between two structural pillars, referencing the biblical story of Samson and the work of installation and media artist Dan Graham. The work depends on the shifting perspective of the viewer and the negotiation of perception in the space. The work functions as a lattice work of triangles, a loaded Star of David, and in relation to the nearby figurative sculpture, in wood, by Ralf Sander, which stands in the same optical field. While formally distinct – Brennan’s work is non-figurative, or non-illustrative, and Sander’s is resolutely somatic – the works share a long ‘conceptual’ ‘tail’. They resonate within a trajectory of understanding and connections the artists make with precedents in art practice, from the recent and more distant past. In Brennan’s case this has to do with the politicisation of space and perception by certain artists, like Graham, of the sixties and seventies, among others, and Sander’s understanding of the painted wooden sculptures of the early medieval era, especially in Germany and Northern Europe, where ideas of the individual and the collective were localised, mythically, in trees and the forest. But also the photographs of August Sander who set out to document human ‘types’ within a particular time and place. In the face of this work I am reminded of Thomas Hirschhorn’s statement that the task is not so much to “make political art, but to make art politically” and that means, for me, without innocence.

The negotiable space inhabited by these artists is recognised and acknowledged as not exclusively Irish. There are increasing continuities between the works and practice on show here and transnational art activity, practice and discourse beyond Ireland. The artists have each instigated dialogues between idea, material and form and the curator’s selection has instigated dialogues between artists and between specific works, the space, context and history, including art history.

While the physical spaces of the Gallery are not at all gloomy they could, in different hands, become oppressive and limiting, but the intelligence of the work, and its emotion – for this is not a cerebral exercise at all – is articulated with a lightness of touch, so that the spaces are somehow enlarged in the mind.

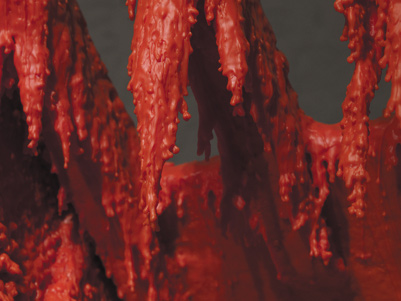

The apparently toytown images of Brendan Jamison, where JCB buckets, of various sizes and types, which are synonymous with the building industry and urban change, are coated in brightly coloured, dripping wax, are, at once, a reference to a past childhood and innocence and also a depiction of nature reclaiming a man-made artefact or tool. While recognisable as man-made, the coated buckets are on the verge of looking natural, as if perceived now, at a point frozen in their transformation – ‘in between’. The individual pieces here act as catalysts for an enlarged reading beyond their strong aesthetic presence.

In Janet Mullarney’s piece, Inequivocal, wax is also used, but here as a sort of flesh on two undetermined, but animal rather than human, creatures set in a ‘pietà’ pose in a vitrine on top of a table. There is also funereal silk in the base of the vitrine and the beings seem still and forlorn. The work has a powerful presence and merits its own low lit vault and, drawing, as it must do, on the artist’s own experience, asks the viewer to contemplate, as she says, “ the unavoidable quality of pain and loss.” It is typical of Mullarney’s practice to provide us with proof of existence even as she acknowledges its inevitable loss.

An awareness of figurative sculptural tradition underpins the whole exhibition, directly, in the work of Mullarney and Sander, whose works negotiate that canon, and indirectly in Brennan’s non-figurative statements. So too in Barbara’s boy by Alan Phelan, who plays with science fiction references and also the sort of mid–twentieth–century sculpture represented by the work of Henry Moore and Barbara Hepworth. Their work merged human and natural forms together and they morphed (as with the Odo character in Deep Space Nine or the pursuer in Terminator 2) into third forms. Phelan knows this to be artifice and understands that science fiction, at least, admits that pretence whereas much of this art and its written history does not. The artist ‘plays’ in the space between those different kinds of knowledge which are ultimately determined by context. Barbara’s boy is covered in newspaper cuttings, the most throwaway and impermanent material, and could not be described as ‘standing on a plinth’ as the figure lies practically at a right angle off it. The piece is out of balance, a statement of sculpture on plinth and a contradiction of it, at the same time.

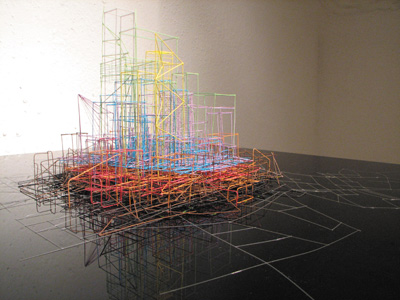

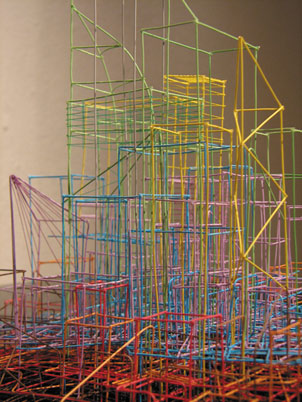

Cristophe Neumann’s work also uses ephemeral material, from the non-art world, in his wall mounted pieces – mostly disused packaging, where the messages of consumption are disrupted and reconfigured to create enigmatic images which are exquisitely made and, paradoxically, themselves become desirable. More is the byword of consumption and is also a wall–mounted piece with the look of a Roman mosaic, reflecting what may be just how this culture’s legacy of desire will be described by future archaeologists. When future excavations do take place, if those societies have JCB technology to hand, of course, we can wonder what they will make of the millions of miles of our telephone cabling, without which present society could not function. Maggie Madden takes this multi-coloured cabling – once, as she says, “ a coded hidden system for aural communication” and exploits its “more random visual function.” In Untitled drawing 2008 fine wiring is manipulated to create, on a plinth with a glossy, black reflective top, what reads as a cluster of high– rise structures. A web of fine wiring is spread horizontally across the surface and the lines seem inevitably to coalesce, intricately and beautifully, into urban structures. Madden has constructed a metaphor for the sort of mid Western American cities – where networks of roads traverse vast open prairies and then race through suburbia to a group of business and commercial buildings – the sort of cities which, for a time, supplied the model for urban development in these islands. The momentum reflected is of the prairie to the city, from the horizontal to the vertical, from the female to the male and from nature to culture. The sense of a potentially endless web of such rural–to–urban configurations is evidenced by those cities in the United States, but the metaphor is also powerful in reflecting, through the use of a material designed for global communication, a societal model which is being universalised by economic and cultural globalisation.

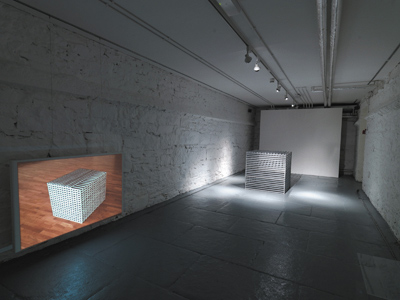

Martha Quinn uses a natural material – limestone – cut into lengths at the limit of the stone’s ‘capability as a material’; in other words, if the lengths of limestone were any longer they would break. Initially, these lengths of limestone don’t look like stone because they actually look too long and, as stone, begin to look unnatural. In the context of a gallery installation, as opposed to work in the public domain, time can be taken to ‘read’ the work slowly. Time is also measured by the projection, on a wall, at low level, which repeatedly shows the removal of the lengths of stone from Cube, to reveal a central void. The artist Frank Stella once said of his own work, famously or notoriously depending on your point of view, that “what you see is what you get.” This position opened the door to a subsequent generation of artists who, at first, were read a simply ‘literal’ Minimalists or reductionists, such as Lewitt and Andre, but whose work is increasingly read as metaphorical and also poetic. With Andre, in particular, the poetic is impossible to avoid. While procedure and process was central to Minimalism, and is also central to this work by Quinn, she has managed to establish parameters within which the procedures and processes take place, which absorb context and politicise, in Hirschhorn’s sense, the act of looking. The void at the centre of Cube, though real, is poetic and metaphorical rather than literal.

The Space in between, therefore, is a synopsis, an ‘object lesson’ in contemporary sculptural concerns and practice that would stand wherever it were shown. The exhibition erases inherited categorisations across which the artists mark out their cross–referencing propositions about negotiable process and space. Working from within their own practice and understandings of art and historical contexts, each artist has managed to speak in their own voice but also dialogue with other voices in the show. This is, of course, a measure of the curation and the capacity of the gallery context to test the art.

In this period this process has to be an essential characteristic of publicly funded gallery/ institutional provision, as we try to create new models of practice and reciprocal relations between artist and society.

We have all eaten from the tree of knowledge and cannot go back to Eden, and this art reflects both the complexity of a new reality and our complicity in it.

Declan McGonagle is Director of the National College of Art and Design, Dublin.