.jpg)

There is something very sweet, very moving about tugging a lever and peering into the activity of a private little world, and the satisfyingly mechanical slotting open and shut of flaps which illuminate it to varying degrees or manifest further layers. Trying each lever of Eye Box 2 in turn, I feel something akin to the simple joy of setting a snow globe aflutter. If the installation cannot be readily visualised, it is because Clifton Dolliver’s “three-dimensional diorama installation” (as described by the exhibition leaflet) is the unique brainchild of a craftsman with puppeteering roots, an artist possessed of marvelous imagination and well versed working process – you really do just have to try it out for yourself. What I’m trying to communicate is that it made me smile.

The contents of the box are novel and intricate enough that I was happy to simply peer into it, when the artist found me at this and asked if I’d pulled the strings. I hadn’t. “That’s the best bit,” he tells me. The levers are rigged up to open different hatches in the roof and the side of the box, inviting window light to illuminate the interior to varying degrees. The effect is one of perceptual manipulation, or trickery, like the way that the eye is tricked by a kaleidoscope. That the viewer has an active role, that of shedding light, can be seen symbolically; as in perception, subjective involvement is required. The eye box is a peek into the workings of the eye itself: things are brightening, morphing, inverting.

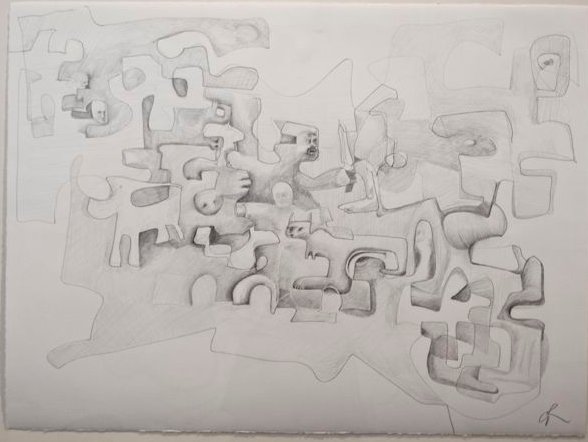

But what does the eye actually meet inside the box? To use a term encountered generally in relation Miró (although any visual similarity is superficial), I find what I want to call biomorphic forms, which are like writhing things becoming – firmly delineated and self-contained, though inconclusive. Double-ended, the box houses Dolliver’s forms in two modes of existence: at one end – that which more closely simulates perception itself – we find dislocated floating entities, while at the other they are peopling what can be reductively described as a landscape. Essentially, and significantly, they are encountered located and dislocated – with and without home.

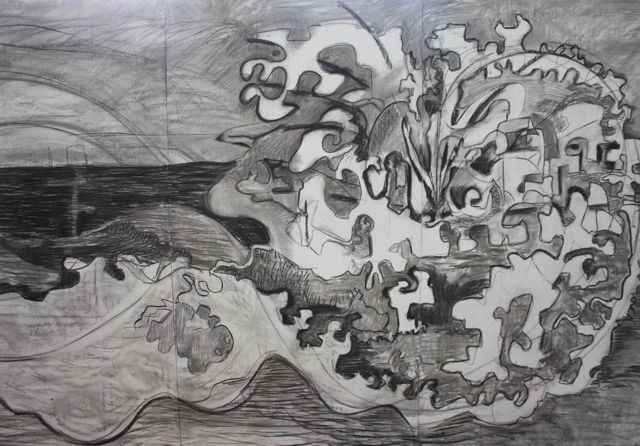

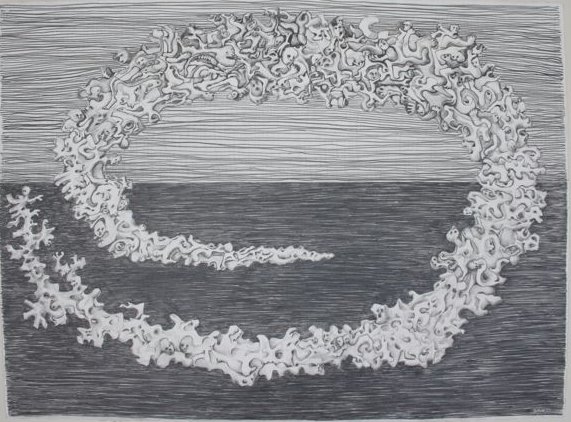

The Eye Box itself evolved out of Dolliver’s wonderful drawings, their nomadic entities born of a wandering line lassoing the bulk of objects and then forgetting the details, becoming something autonomous. Sometimes, as in Colony, their anatomy is so particular that they look like the things that bones could have been. It makes sense that these restless creatures wanted to escape the two-dimensional. Having made the leap from drawing to sculpture, they remain like things cut out and stuck on. Marrying the two mediums, as the exhibition does, is an invitation to the viewer to question what it is about the drawings that is conducive to sculptural form. In contemplating their journey – popping forms peeling from the page and slapping flatly into the realm of sculpture – we can see them as nomadic, exiled, not settled in either land. In the drawings themselves they form a procession; tumbling, marching from one frame to the next, being swept up, floating, stumbling and always reconfiguring.

The constant elements across both mediums are light, water and land; their collective ordering is dreamlike, as if they have been hauled at random from the depths of a mind which failed to make sense of them while awake. They convey a feverish interpretation of something half remembered.

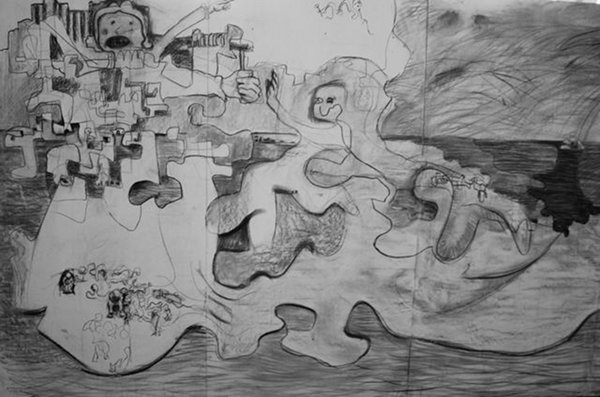

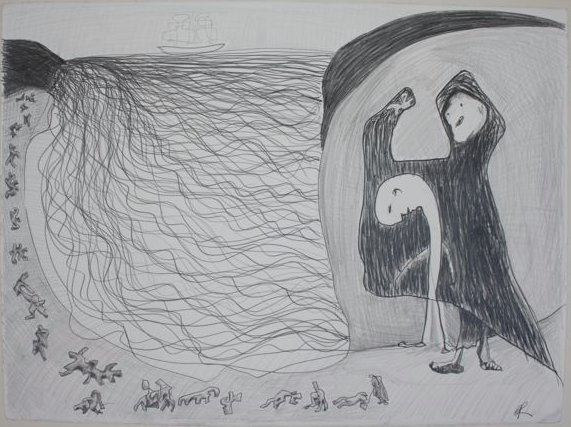

Dolliver, I will wager, is a storyteller, and overall there is a sense of narrative, but one which is rendered inconclusive and open-ended by abstraction. It is not an abstraction which makes no reference to the world; it is rather a pinning down of the moment when the abstract begins to fill out the form of an object. While stopping short of conclusiveness, the exhibition does not intimidate; its childlike style and interactive theatricality mean it is accessible and universally familiar, inviting a playful approach, open to personal elaboration. As if executed by a child, the drawings employ scribbled-in shading and your standard figures-set-against-horizon-line formula; their composition is intuitive and memory-based. Where narrative drama is present, as in Secret River and Exodus, it is with a Poussin-like (this I substitute for childlike) clarity – the eye easily led. At least this is what their compositions succeed in conveying, yet what are we to conclude from these strange scenes?

This innocent style, which suggests a fresh-eyed, noncontextualised grasp of the world, is contrasted with the exhibition’s rightful subject matter: the British invasion of Australian territory. A born Tasmanian, Dolliver inherited a certain cultural consciousness of this period in history. For the Aboriginal people, he tells me, it is an ill-recorded one; without an official story, it is a soup of tall and conflicting tales. The takeover met with little resistance, as the natives were not equipped either to fight or fully grasp it. As a result, it is a forever-muddied memory, resistant to penetration. His style is possessed by this incompleteness, this yearning for comprehension. It captures something of the naivety with which those, for whom land ownership must have been an alien notion, faced their exile.

That colour is absent throughout is the initial feature to jar with a reading of the style as wholly childlike, instilling suspicion. To colour in would be to particularise, to fix something that resists pinning down. The emphasis is on form and relationship, the arrangement of contents in a memory that cannot be focused in on.

We encounter his dislocated creatures in a variety of configurations – some (like Secret River and Exodus) more representational or fully-formed than other, more frantic or surreal compositions (like those of Linkage and Flux). Multifaceted and shifting, a past is presented which is peeked only through dense rainforest, constructed out of the clouded recollections of disorientated convicts.

It is a history so deeply buried in a national psyche that it cannot be extracted whole; it devours itself and spits up half-truths. In Swarm, there is a feverish sense of things melting and building up, of the constructive and destructive forces at work just before and after things are fully themselves.

Flux is a tangle of impossible sculptural forms, each melding into its neighbours so that it must remain a confused whole with no extractable element. In contrast, we have Colony. It depicts a hovering group of forms, which appear unnervingly ineffectual in their setting. They are about to move or fill out; they should fit into each other but won’t, remaining hopelessly isolated.

A mural of sorts is drawn onto the side of the installation box. Urgently, dramatically rendered, it makes me think of the wall-drawings of someone who has been locked up and gone mad. Notably, it physically provides the context for the installation, linking the two mediums. Domineering colonial personae and a cluster of feeble figures – tangled and clutching and confined to a scale too small, too trampleable – are washed up on an enormous wave alongside glimpsed traces of creatures from the sea, culminating in a swirling bloom of festering form. (The word ‘festering’ was offered by the artist himself, and you can nearly hear it, garbled and buzzing.)