‘how to make a refugee’ by Phil Collins was shot in 1999 in response to the Kosovo conflict in May of that year. This film, the artist’s first, focuses on a photoshoot with a family who have been displaced by the fighting. In the brief but lingering 12 minute video we see a nondescript scene which reveals a another horror of war; not a scene of violence, but international media casually staging a family of refugees to get the best angles for us, the voyeurs at home.

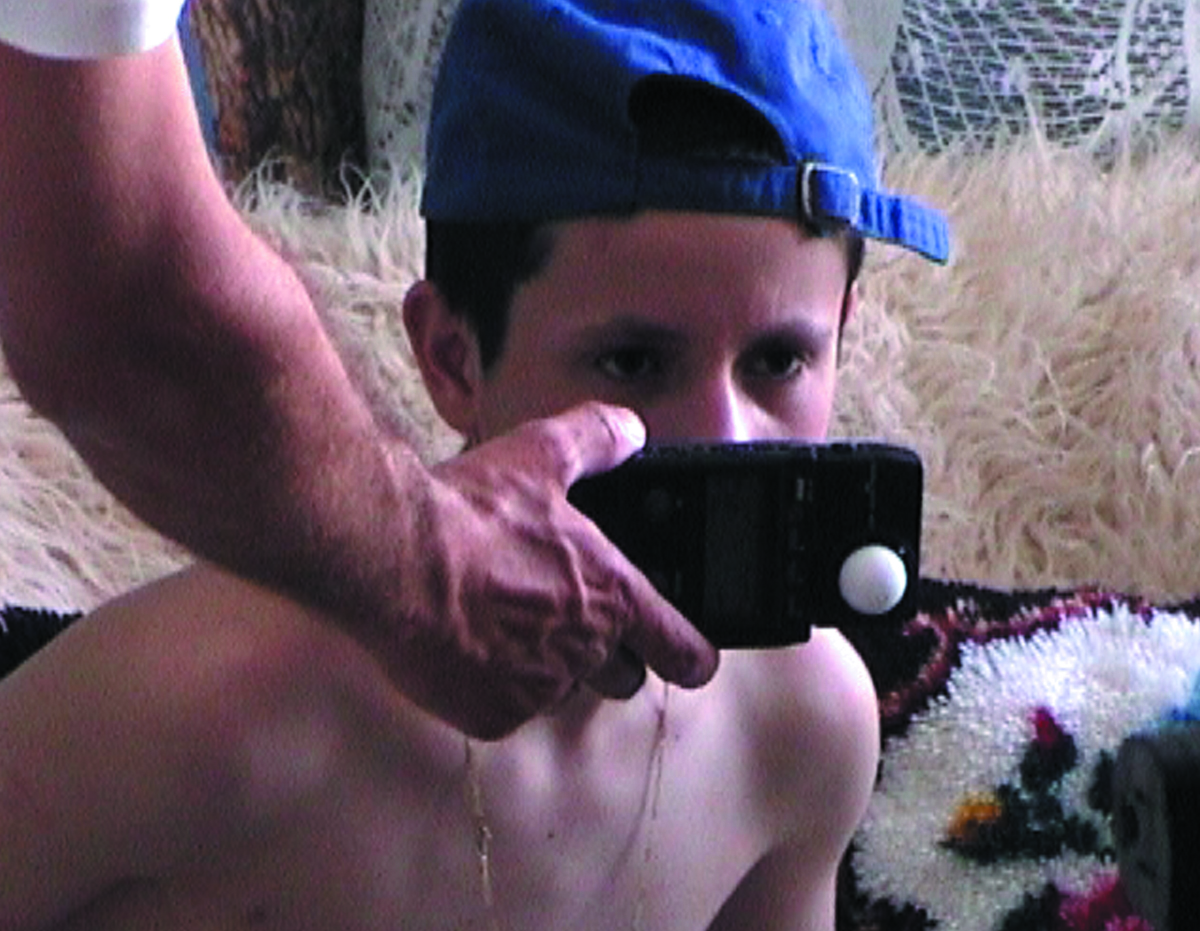

In this work, Collins asks questions about the machinery of the media without having to say anything at all. We are far beyond the question of whether or not it is right to look at victims and violence, we are witnessing the everyday-ness of the attention economy happening. The opening shot shows a boy who, we later learn, is 15 years old; he wears a thin gold chain, and answers through an interpreter a journalist’s questions about his interactions with the police and what happened to his family. The journalists discuss whether or not it looks better for him to wear his cap; early on they remove his shirt to show a large scar on his abdomen.

In many ways, the film is boring (although that is hadly new or novel in the history of video art). Mostly, the subjects at hand are still. The boy with the blue cap poses, and dispassionately answers the translator facilitated questions. We turn to the rest of the family; a grandmother who holds her arm around a young girl, and another group of kids who sit on the edge of the frame or on the ground silently staring. All throughout this steady process, a camera snaps in the background and occasional flashes pop – a tragic paparazzi caught on a muted 90s styled home video recording. Click.

To watch this again in the age of ‘fake news’ is a curious spectacle. Today, the media – or at least, those aspects of the media which dominate and capture our attention – feels entirely removed from reporting on the ground, or any kind of reporting at all; it’s all press releases, clickbait and hot takes. We are all splitting off eagerly into our own little bubbles. Some election fraud for you, a little Bernie-would-have-won for me; social media outrage for us all. Even seeing a certain kind of manipulation take place IRL, off-screen and offline, holds a certain anachronism which makes thinking about fake news, already spun into a cliché through the pace of digital publishing, feel like something that could be made sense of again.

The datedness of this artwork is useful, registering on more levels than just its aesthetic and concerns about how truth is staged. It captures how critical conversations have changed over time. When was the last time anyone was concerned about the ethics of image culture, and they weren’t talking about identity politics? Perhaps it was Kosovo in 1999, led by people like Susan Sontag. Sontag was one of the great critics of the 20th century; a period where we began to abandon the term great; just as the time was defined by war, genocide and the pervading fear of nuclear extermination. It was in this context, a little after images of conflict and suffering began to circulate through a 24/7 news cycle that Sontag grappled with the profound moral questions of what it meant to depict violence, war and those regarded as outsiders. She was deeply committed to the humanitarian cause of Kosovo, and had little time for artists who found drama in the pain of others.

Collins has been described as a prankster, which feels very close to the 90s and early noughties edge which gives his work its critical and adolescent appetite. We sometimes refer to this as post-documentary to suggest that the deadpan approach is a style to be considered and backed up by a combination of intentionality and theory. When he was nominated for the 2006 Turner Prize, he embraced this by setting up Shady Lane Productions, a semi-fictional production company, to create a film about former reality TV participants reflecting on their experiences of instant fame and exploitation. Collins’ artistic career has charted this rapid pace of image culture and ethics; namely, how things got faster and more exploitative following the intensification of the 24 hour news cycle and reality TV. Every few years, perhaps it’s every few months, we stumble across a new spiritual vector for what we could call our ‘cultural moment’; a highly augmented social media star in the vein of Kim Khardashian; the scammer ala Anna Delvey; the anonymous alt-right troll; woke Twitch streamers like Hasan Piker; and whatever is happening on TikTok.