Brian Davey reviews States of Entanglement: Data in the Irish Landscape, the accompanying publication to Entanglement, the Irish Pavilion at the Venice Architecture Biennale by ANNEX*.

In the summer of 1858, the first transatlantic telegraph cable was successfully laid between Valentia Island, County Kerry and the town of Heart’s Content, Newfoundland. One of the first messages to be transmitted via this new technology was an exchange of well-wishes between Queen Victoria and US President James Buchanan. Meanwhile, the Mayor of New York, Daniel F. Tiemann, sent telegrams to the Lord Mayor of London, as well as the residents of Mallow, in County Cork. Mayor Tiemann, upon receiving a reply on behalf of the inhabitants of the Mallow, addressed an assembled crowd in Manhattan, saying: “I have here, a message from a little village now a suburb of New York.” Tiemann’s statement echoed a common feeling at the time, that the success of the telegraph would result in the map of the world being redrawn. Places like Mallow were no longer to be peripheries. Thanks to the telegraph cable they were now as close as Manhattan.

Although practicably inefficient – and prohibitively expensive – the transatlantic telegraph still signalled an important moment in the history of communications. As one American newspaper declared at the time: “This is indeed the annihilation of space.” Messages were now untethered from modes of transportation and would no longer have to be conveyed via sea or rail with all of their attendant delays. As Professor Chris Morash points out in his contribution to States of Entanglement: “Information became a separate entity, distinct from the space it occupied, whether in motion or at rest, It became, in our terms, data.”

Data has since become an inextricable part of our lives, though this has been more pronounced since the Covid-19 pandemic began. Our workplaces, social lives, and relationships are now mediated through the online world; their opportunities and limits shaped by the designers of digital technologies. This reliance on data is so overwhelming that it has become largely invisible to us. Unless something goes wrong, we seldom stop to consider the infrastructure that enables us to send a Tweet via a phone app or conduct a Zoom meeting on a work laptop. For example, if you’re scrolling through Twitter and click on a link to this review, a request will go from your device (whether it’s a phone or laptop) via your internet service provider to the web server. After a moment’s loading, it will take you to this very page. A fairly seamless transaction that will ordinarily take just a few seconds.

Every time we perform such an action online, a small amount of electricity is used and C02 is produced (sending an email emits about the same C02 as leaving a lightbulb on for half an hour), which means that Data centres are consuming vast amounts of high quality electricity. One paper published in Science last year suggested that data centres account for “1% of the global energy demand.” As of November 2020 there were 66 such data centres located in Ireland, which accounts for around a quarter of all available server space in Europe, with many more in the planning stages. Owned and operated by tech companies based in Ireland, such as Amazon, Google, Microsoft and Facebook, these centres are integral to their cloud-computing operations. A paper published by Enterprise Ireland in 2017 explained that tech companies have had to refine the design and construction of their data centres in order to accommodate the growing scale of daily transactions that take place online: “four billion searches a day (Google), 500 million tweets (Twitter), 254 million orders in a day (Alibaba), 350 million new photos per day (Facebook).”

If we add all this together, it means a proliferation of data centres and increased pressure on our environment. In Ireland, “[o]ne proposed Amazon facility is forecast to consume four percent of [the country’s] electricity demand. Collectively, the data centre industry is expected to consume thirty-one percent of Ireland’s total electricity output by 2027.” In addition, data centres emit enormous quantities of heat, so that the servers, if not kept at an adequate temperature, will cease to function properly. With its colder climate, Ireland is an attractive location for tech companies who wish to reduce their cooling costs. As more organisations migrate into the cloud, this means that the number of data centres will only grow.

The use of the term ‘cloud computing’ can be deceptive. A cloud suggests something lighter than air, vaporous, untethered to the earth, and is a good example of how the tech industry keeps its operations out of sight. Bear in mind that the term ‘cloud’ can also be used to mean an obstruction or opacity (The Cloud of Unknowing…). It is the concealment of data’s environmental impact, as well as the infrastructure that supports it, that the architecture collective ANNEX wish to highlight in Entanglement, the Irish pavilion at the 17th International Exhibition of La Biennale di Venezia. Entanglement, in the words of ANNEX, seeks to “uncloud the sleek aesthetic of an industry which is forming our realities.”

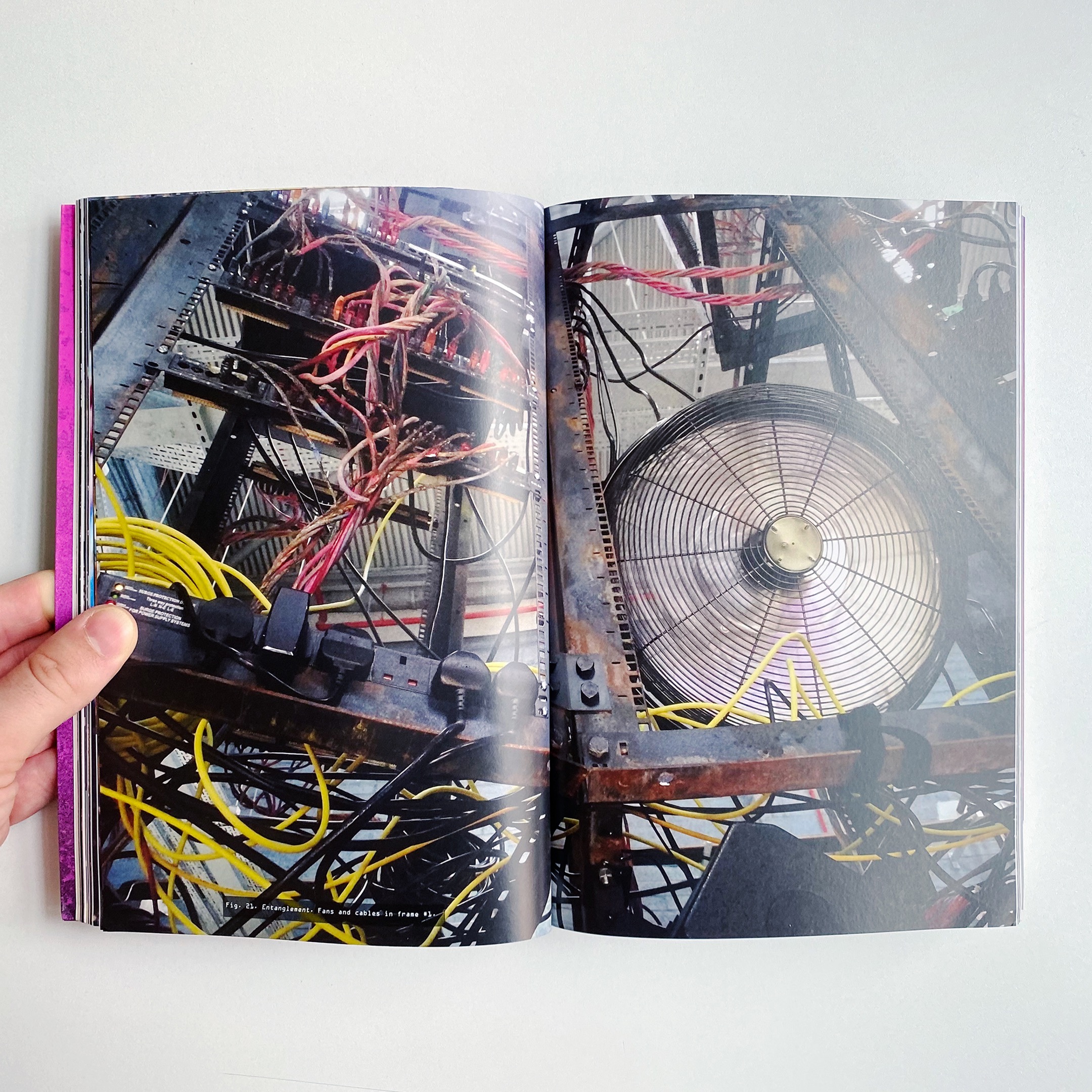

The main pavilion structure itself consists of server racks (the frames that house computer servers) arranged in a circular pattern and stacked in tiers. The racks have had their surface scraped away and have been torched until charred and blistered by the heat, in order to better undermine the tech industry’s “aesthetic fetishism propaganda” of frictionless digital technology. It looks like a post-apocalyptic techno totem pole built to commemorate the past digital age.

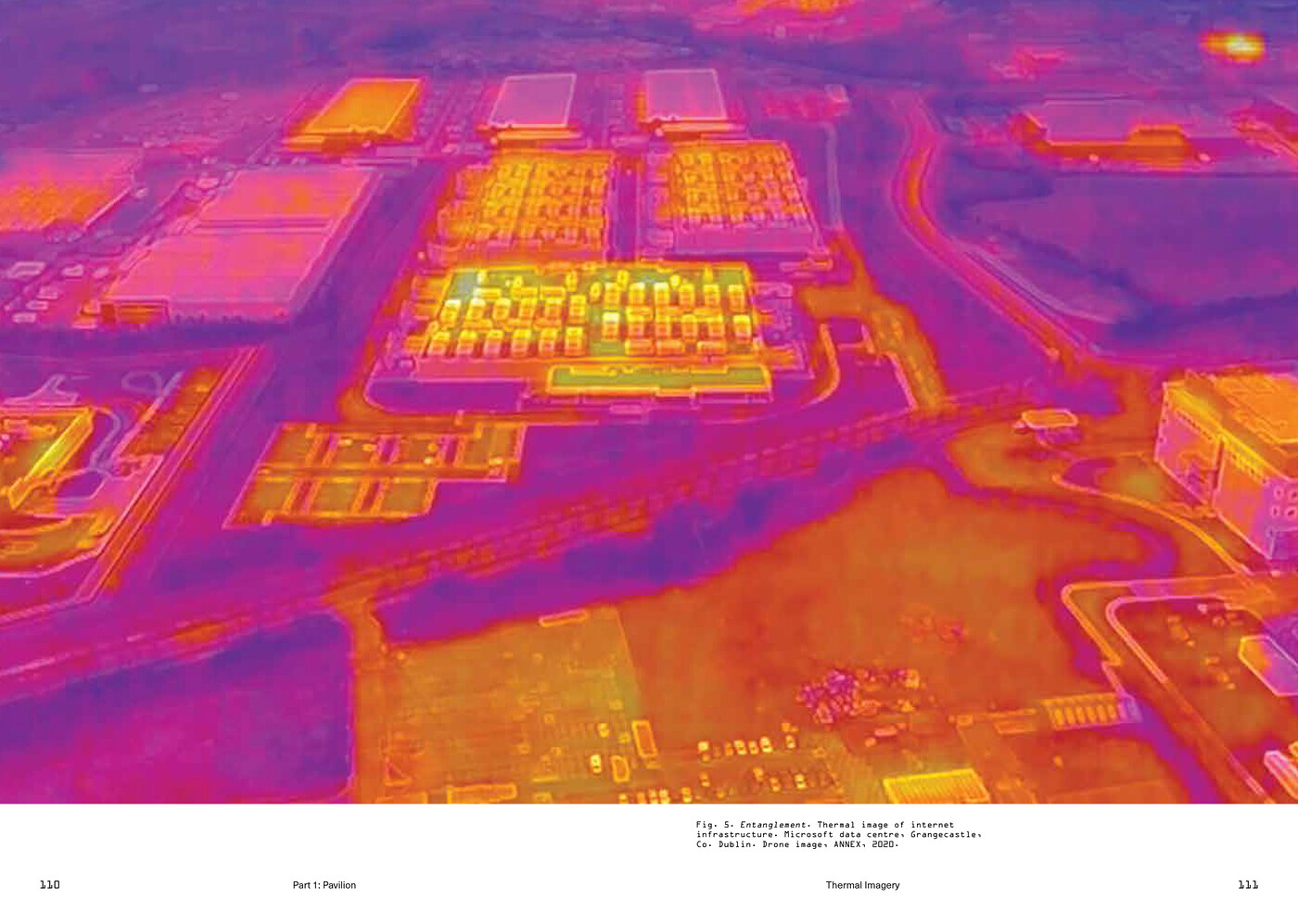

Typically, data centres are located in industrial estates, with little to distinguish them from the surrounding businesses. However, Entanglement also features thermal footage of the centres captured by drones. The surrounding landscape is coloured a cool, hazy purple while the data centres, producing large amounts of waste heat, are intensely white. It’s a striking image that makes explicit what is usually an invisible process. As ANNEX put it in their introduction to States of Entanglement: “the thermal forces underpinning this planetary-scale network of information exchanges has receded from view.”

One tech company, Amazon Web Services (AWS), has even tried to capitalise on this heat produced by their servers by creating a system called ‘Heat Works’ which will recycle dead heat from their centres for use in the Tallaght community, including the Civic Theatre, Tallaght County Library, and the contemporary arts space, Rua Red. But despite these efforts to greenwash this issue, data centres remain incredibly resource intensive, and their stated green energy goals seem dubious at best. As ANNEX member Donal Lally put it: “Many people think the Internet is magic and that the cloud is ethereal, but really it’s dirty and heavy and very demanding on the Earth’s natural resources. The lithium in the battery of your phone is mined; silica, one of the oldest rare earth minerals, is used in fibre optics; and cobalt is mined (often illegally) for batteries.” The tech industry works hard to conceal these operations.

States of Entanglement, which has been published to coincide with the pavilion, is part exhibition catalogue, part scholarly examination of the role of data and its interaction with the landscape. The first section of the book breaks down some of the key strands of thinking behind Entanglement by the inclusion of emails and Slack messages exchanged between members of ANNEX. Through these fragments of digital ephemera it shows the genesis of Entanglement’s concept and how the structure itself was built.

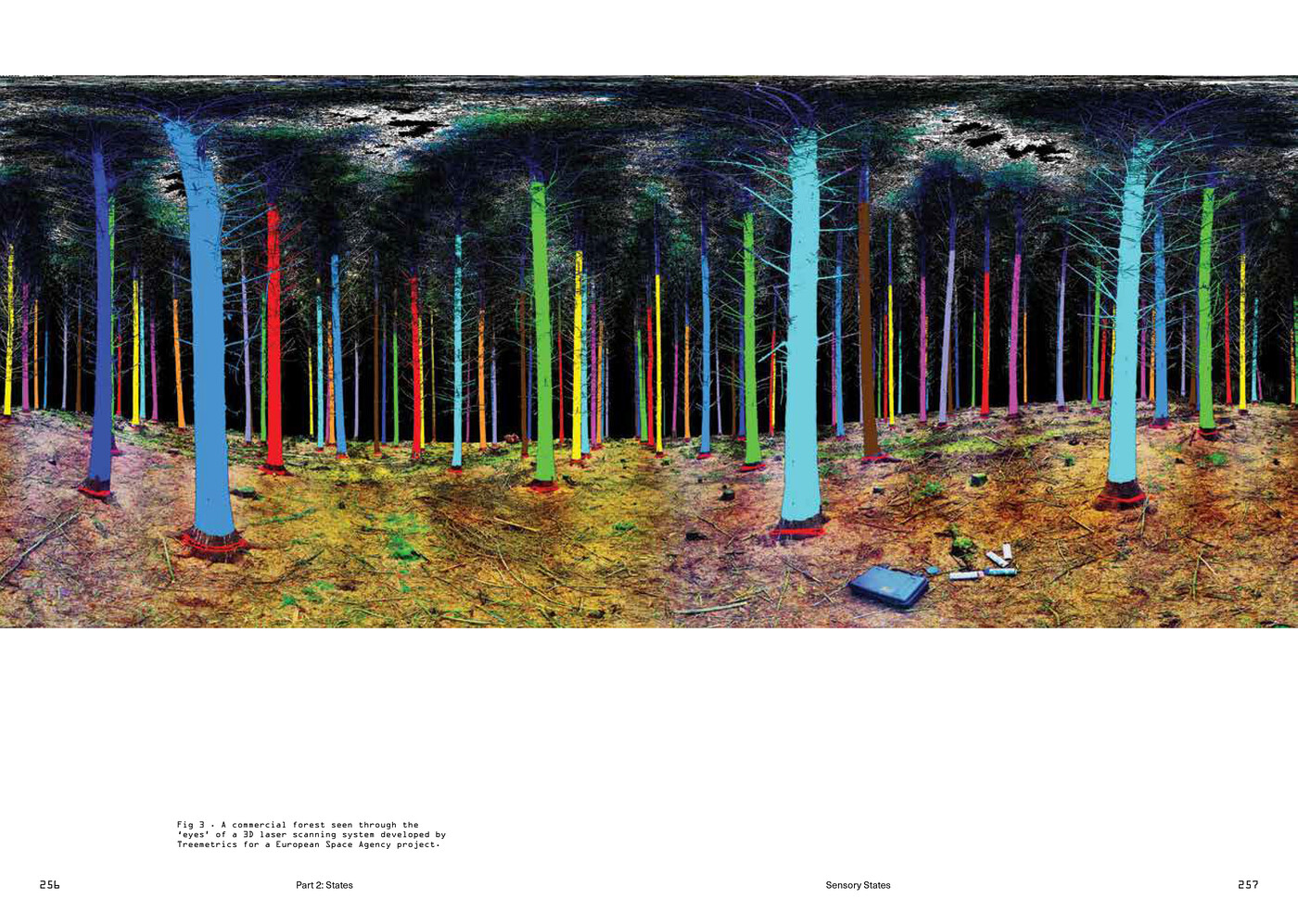

The second section moves away from the pavilion and instead, examines the subject of data in the Irish landscape generally via a series of essays, covering topics such as the politics of data and energy in rural Ireland, the history of the cable station on Valentia and the semiotics of how temperature is conveyed in thermal imagery. It serves as an overview of the topic of data centres in Ireland and an introduction to many of the ancillary issues around this. The book is richly illustrated with the design complementing each of the texts.

One of the contributors to States of Entanglement, Dr. Patrick Bresnihan, is a lecturer in the Department of Geography at Maynooth University and he recently made a statement to the Oireachtas Committee on Environment and Climate Action about data centres. In his statement, he pointed out that Ireland could potentially risk a backlash for a moratorium on the construction of data centres but “the prospects of energy insecurity may carry greater reputational and economic damage… Further down the line, there is also the reputational damage and financial penalties for Ireland if it fails to meet its 2030 climate and renewable energy targets.”

When I began reading States of Entanglement in July for this review, Ireland was going through a record heatwave. I then had to travel to Hamburg for a week and brought the book with me to read. In the hotel, the only television stations in English were the news channels. Al Jazeera reported on the wildfires in Turkey, CNN on the wildfires in California, and Russia Today showed the wildfires in Siberia. Walking through the streets of Hamburg, there were electronic adverts displaying images of the recent flooding which had devastated western Germany, along with a text-to-donate phone number in order to help the victims of the floods. I finished reading the book the same day that the IPCC’s climate change report was published. Its prognosis was clear: man-made activity has put us on course for a climate catastrophe.