Mother Ireland and the Troubles

Belinda Loftus

Both Mother Ireland and the women of the North have been depicted by numerous Irish artists during the past twelve years. These works exhibit certain shared characteristics. They bring into the open the ambivalence implicit in Irish female symbolism and their handling of female imagery is strongly conditioned by artistic conventions which act as subtle gatekeepers of perception. This is particularly evident in the work of artists distanced by class or geographical removal from the realities of the Northern Ireland conflict but can also be seen in the output of those immersed in those realities.

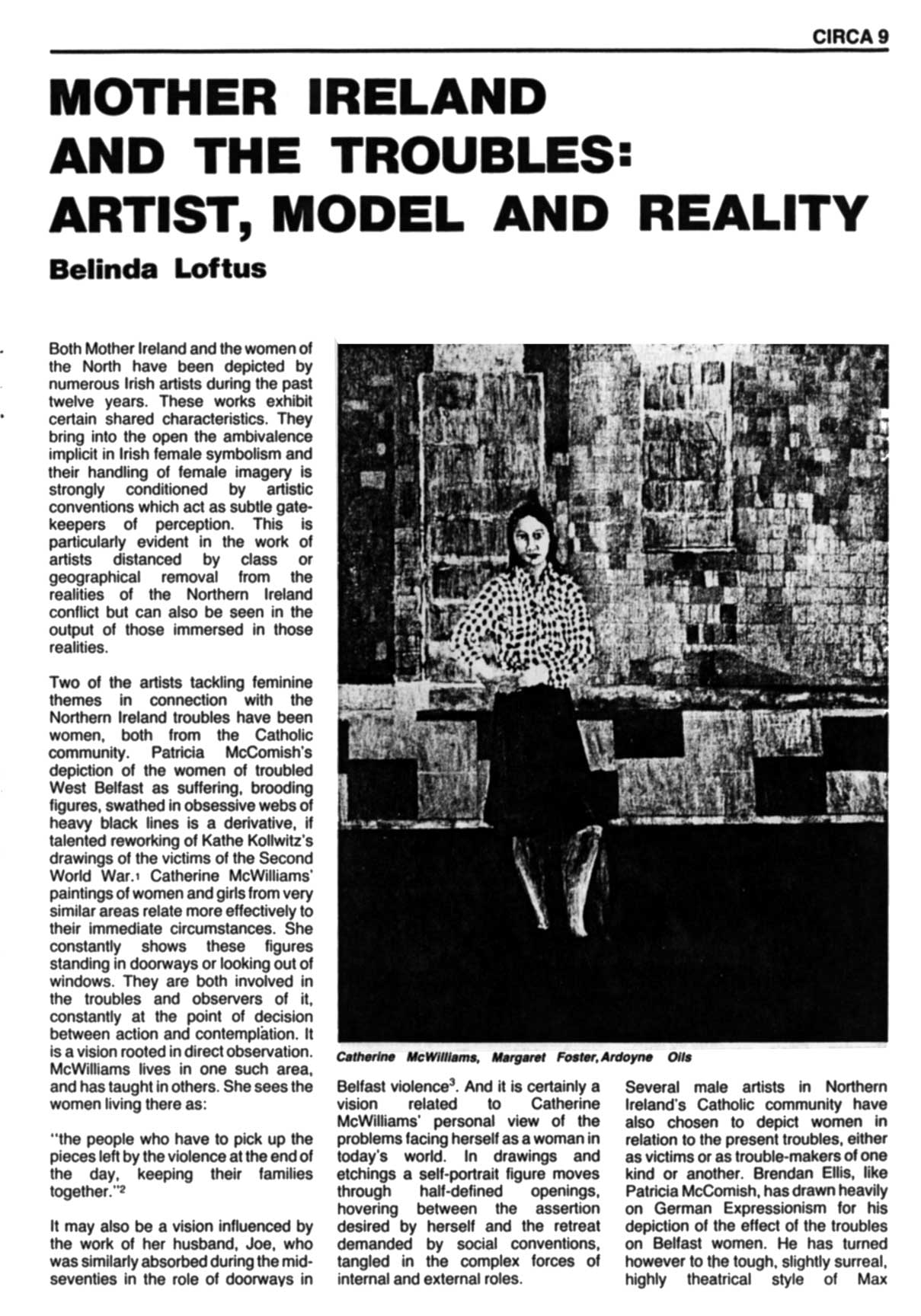

Two of the artists tackling feminine themes in connection with the Northern Ireland troubles have been women, both from the Catholic community. Patricia McComish’s depiction of the women of troubled West Belfast as suffering, brooding figures, swathed in obsessive webs of heavy black lines is a derivative, if talented reworking of Käthe Kollwitz’s drawings of the victims of the Second World War.1 Catherine McWilliams’ paintings of women and girls from very similar areas relate more effectively to their immediate circumstances. She constantly shows these figures standing in doorways or looking out of windows. They are both involved in the troubles and observers of it, constantly at the point of decision between action and contemplation. It is a vision rooted in direct observation. McWilliams lives in one such area, and has taught in others. She sees the women living there as:

“the people who have to pick up the pieces left by the violence at the end of the day, keeping their families together.”2

It may also be a vision influenced by the work of her husband, Joe, who was similarly absorbed during the mid-seventies in the role of doorways in Belfast violence3. And it is certainly a vision related to Catherine McWilliams’ personal view of the problems facing herself as a woman in today’s world. In drawings and etchings a self-portrait figure moves through half-defined openings, hovering between the assertion desired by herself and the retreat demanded by social conventions, tangled in the complex forces of internal and external roles.

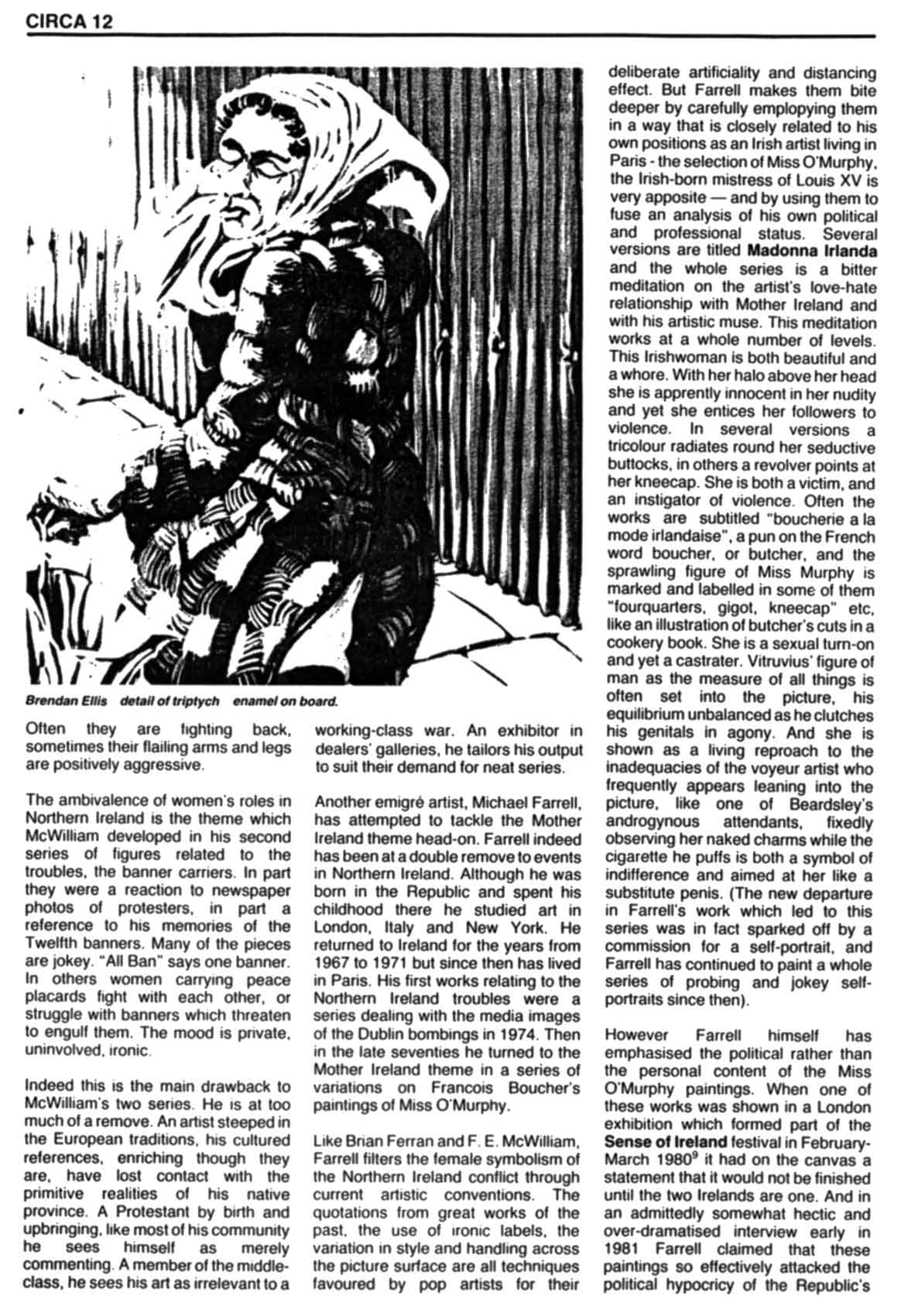

Several male artists in Northern Ireland’s Catholic community have also chosen to depict women in relation to the present troubles, either as victims or as trouble-makers of one kind or another. Brendan Ellis, like Patricia McComish, has drawn heavily on German Expressionism for his depiction of the effect of the troubles on Belfast women. He has turned however to the tough, slightly surreal, highly theatrical style of Max Beckmann as a means of handling the drama of the Belfast streets in which women are lively combatants, suffering but fighting back. The joking factory girls hurrying home from work, the wife or girlfriend leaning forward in her chair to watch the news on the television, the pinched, down-at-heel housewife scuttling along with her carrier-bag, past the corrugated-iron barricades, the girl shocked by some violent incident, crouched in an armchair, wrapped in a dressing-gown, the brassy tarts down in the pub – these are the women of Belfast’s troubled streets, at once vulnerable and intimidating.

The same expressionist handling of Belfast women’s day-to-day lives can be found in Martin Forker’s series of drawings made in 1975 while he and his wife were living in Turf Lodge, one of Belfast’s most depressing post-war Catholic housing estates. Forker, who was unemployed at the time, was witness to many of the intolerable strains imposed on local women, including his own wife. One of their neighbours was Rosie Nolan. Separated from her husband, mother of a mentally handicapped child, living in an appallingly sub-standard flat, she eventually hanged herself. Forker’s drawings of her fate and of the situation of other local women are heavily influenced by German expressionism, like the works by Patricia McComish and Brendan Ellis, but they are also strongly rooted in such immediate circumstances as oppressive architecture, squawling kids and endless nappies. Curiously though, when Forker attempted a painting of Mother Ireland and her child, which he intended to be “a monumental image of suffering”, he used as its visual basis not one of the scenes around him in Turf Lodge, but a photograph of an itinerant woman and child in Edna O’Brien’s book, Mother Ireland4.

Other young artists in the Catholic community have presented a more ambivalent view of the Belfast women. Brendan Ellis’s younger brother Fergal has depicted her as close to the heroic mother image of 1916, child in one hand, rifle in the other, contemplating the graves of her martyred men. The image also has a private meaning. The gun symbolises for this artist the marital strife which he sees as widespread in Northern Ireland.

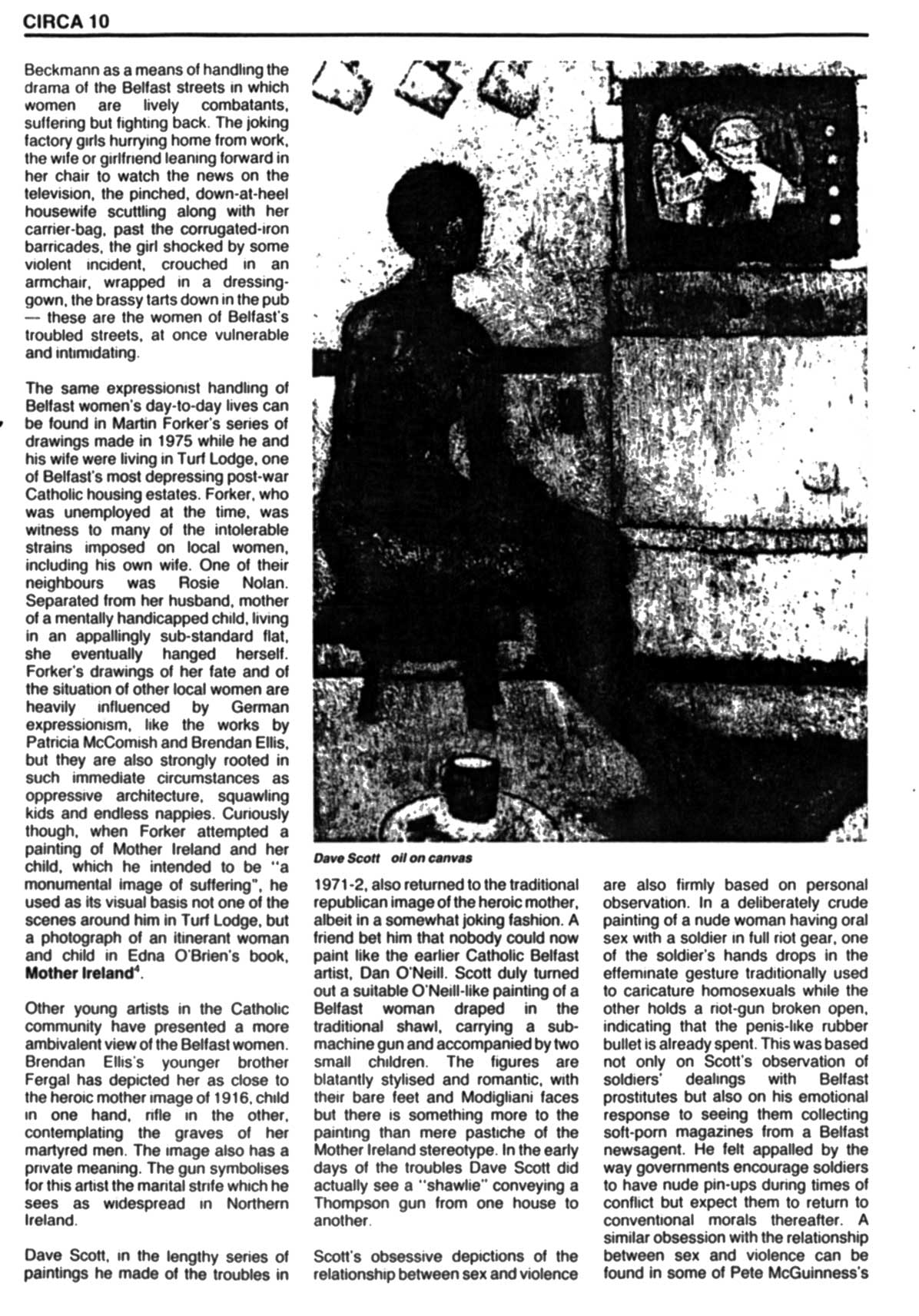

Dave Scott, in the lengthy series of paintings he made of the troubles in 1971-2, also returned to the traditional republican image of the heroic mother, albeit in a somewhat joking fashion. A friend bet him that nobody could now paint like the earlier Catholic Belfast artist, Dan O’Neill. Scott duly turned out a suitable O’Neill-like painting of a Belfast woman draped in the traditional shawl, carrying a submachine gun and accompanied by two small children. The figures are blatantly stylised and romantic, with their bare feet and Modigliani faces but there is something more to the painting than mere pastiche of the Mother Ireland stereotype. In the early days of the troubles Dave Scott did actually see a “shawlie” conveying a Thompson gun from one house to another.

Scott’s obsessive depictions of the relationship between sex and violence are also firmly based on personal observation. In a deliberately crude painting of a nude woman having oral sex with a soldier in full riot gear, one of the soldier’s hands drops in the effeminate gesture traditionally used to caricature homosexuals while the other holds a riot-gun broken open, indicating that the penis-like rubber bullet is already spent. This was based not only on Scott’s observation of soldiers’ dealings with Belfast prostitutes but also on his emotional response to seeing them collecting soft-porn magazines from a Belfast newsagent. He felt appalled by the way governments encourage soldiers to have nude pin-ups during times of conflict but expect them to return to conventional morals thereafter. A similar obsession with the relationship between sex and violence can be found in some of Pete McGuinness’s works where photos of the Northern Ireland troubles are montaged with pictures from sex-magazines. Like Scott McGuinness is deliberately crude. The girlie pictures he uses are aggressively explicit, not the sanitised soft-focus images of the mass-media.

In some of Scott’s paintings however, female sexuality is shown in opposition to violence. In one, for example, he shows his wife sitting nude in front of a cooker on top of whose lighted rings is set a television showing a news picture of a soldier wielding a riot baton. Scott recalled that his parents, who were devout Marxists, demanded total silence during the news, while he himself felt his blood boil, as though the television were a saucepan on the stove. The obsession comes home, the anger is contextualised and offset by the gentle curves of his wife’s body, the domestic detail of a cup and plate on the floor and the neat patterns formed by rows of cups and knobs.

Brian Ferran is an older, more middle-class, more established artist from the Catholic community (he is Director of Art and Film for the Arts Council of Northern Ireland), and lives in a relatively peaceful middle-class area of Belfast. He has also used traditional images of Irish women to represent their current roles as both victims and manipulators, but in a more detached and knowing fashion than the painters so far discussed. Ferran has a strong interest in the international art scene and has studied recent trends in both the United States and Italy. The influence of this interest is immediately apparent in Pat, his first major work dealing with the present troubles. This was painted in 1971 after hearing while on holiday in Spain of the death of a girl in Belfast. It is heavily influenced by the collage techniques developed by the Cubists early in the century and revitalised by American and British pop painters from the 1950s.

“Rauschenberg, Richard Hamilton and other Pop painters incorporated photographs, magazine clippings and the like into their works, painted over and around them and produced works which have a narrative content. A ‘reading’ of Pat might begin at the top with the female nude torso which has been personalised by the artist having added paint to the photograph. An arrow and a word tell us this is Pat. The figure and glimpses of anatomy on the left plus the repetition of a single word proclaim that this is Life. The graffiti-like quality is emphasised by the stylised childish drawing of the pigtailed schoolgirl who occupies the central space and by the starkness of the words. In the lower half the arrows point to the left, to Death, and the twice repeated story of Pat has all the verbs changed from present to past tense. The stories themselves are cancelled or crossed out (as in Hamilton’s My Marion series) with crushing finality. This heavily marked picture, with the crosses and chevrons which constantly appear throughout his work, has an irony built on the juxtaposition of the many types of visual communication.”5

In the mid-seventies Brian Ferran turned to Ulster’s great Celtic saga, the Táin, as a source for his paintings about the present troubles. His work at this time continued to stress the theme of suffering women but in closer relation to the traditional concept of Ireland as a wronged and lamenting land. Then, in the late seventies, his emphasis changed, partly as a reaction to what he saw as the over-sentimentalised and over-emotional presentation of women as victims in works by artists like F. E. McWilliam.

“I think I subscribe more to O’Casey’s idea of their being central and of their being in many ways the political manipulators under the surface of the whole thing while at the same time being able to stand removed and say ‘well I told you so.’”6

In a series of paintings about the United Irish uprising of 1798 Ferran featured the rebel heroine Betsy Gray. This redheaded figure, who is clearly modelled on the artist’s own redheaded wife, appears in a whole range of roles, carrying a machine gun, lamenting with upraised arms, or watching impassively, as the battles of ’98 symbolised by variations on Thomas Robinson’s Battle of Ballynahinch, take place in front of her. As with many of the works of the pop art movement a cool, bland almost photo-realist style is used to ironically distance the violence and romanticism of the conflict so that its reality and importance becomes questionable.

It is the kind of vision possible to someone removed from the troubles by social class and involvement in international art styles.

F. E. McWilliam, a sculptor who originates from Northern Ireland’s Protestant community,, has also been distanced from events there by his émigré status – he left the province at the age of eighteen and has lived in London for many years – and by his observance of certain artistic conventions, This distancing has affected his Women of Belfast sculptures in a number of ways

For these works McWilliams could draw on his vivid memories of the previous troubles in Northern Ireland, his continuing contact with friends and relatives in the province, the very occasional visit and the media imagery. From such links with the province he claims to have derived an obsession with the tensions set up by opposing forces, and the curious interrelationship between calm and violence. He has said of his work in general that he likes to provoke things to the point of being off-balance.7

The formal imagery of these sculptures is closer however to European art traditions than the realities of the women caught in the bomb blast. They reel and cavort like medieval figures in the dance of death. Their clothes billow out expressively like the flying metaphoric draperies of such baroque painters as El Greco. Even the wet plaster technique in which they were carried out resembles the free handling of baroque clay maquettes. Some of them use mechanical references, resembling crushed cars or metal pitted by heat, in the same way as Picasso absorbed machinery into his sculptures. Many have their faces covered by drapery, like Magritte’s despairing heads obscured by cloths. It is quite possible that none of these references were in McWilliam’s mind when he made these sculptures. Undoubtedly however his work draws on the full richness of European artistic traditions. He left Northern Ireland because it was so parochial, he delighted in the diversity of his fellow-students at the Slade, he travelled widely, and he constantly displayed a healthy ability to absorb and reutilise what he saw.

The theme of this first series is “the woman as victim of man’s stupidity.”8 They are not specifically sexual victims nor do they appear to suffer any major injury. What they suffer chiefly is loss of dignity and oppression by forces beyond their control, their skirts blown up, their shoes flying, their stockings ravelled, caught off balance, crushed by the corrugated iron which surrounds them, trying to struggle to their feet. Yet they are not altogether victims. Often they are fighting back, sometimes their flailing arms are positively aggressive.

The ambivalence of women’s roles in Northern Ireland is the theme which McWilliam developed in his second series of figures related to the troubles, the banner carriers. In part they were a reaction to newspaper photos of protesters, in part a reference to his memories of the Twelfth banners. Many of the pieces are jokey. “All Ban” says one banner. In others women carrying peace placards fight with each other, or struggle with banners which threaten to engulf them. The mood is private, uninvolved, ironic.

Indeed this is the main drawback to McWilliam’s two series He is at too much of a remove. An artist steeped in the European traditions, his cultured references, enriching though they are, have lost contact with the primitive realities of his native province. A Protestant by birth and upbringing, like most of his community he sees himself as merely commenting. A member of the middle-class, he sees his art as irrelevant to a working-class war. An exhibitor in dealers’ galleries, he tailors his output to suit their demand for neat series.

Another émigré artist, Michael Farrell, has attempted to tackle the Mother Ireland theme head-on. Farrell indeed has been at a double remove to events in Northern Ireland. Although he was born in the Republic and spent his childhood there he studied art in London, Italy and New York. He returned to Ireland for the years from 1967 to 1971 but since then has lived in Paris. His first works relating to the Northern Ireland troubles were a series dealing with the media images of the Dublin bombings in 1974. Then in the late seventies he turned to the Mother Ireland theme in a series of variations on François Boucher’s paintings of Miss O’Murphy.

Like Brian Ferran and F. E. McWilliam, Farrell filters the female symbolism of the Northern Ireland conflict through current artistic conventions. The quotations from great works of the past, the use of ironic labels, the variation in style and handling across the picture surface are all techniques favoured by pop artists for their deliberate artificiality and distancing effect. But Farrell makes them bite deeper by carefully employing them in a way that is closely related to his own positions as an Irish artist living in Paris – the selection of Miss O’Murphy, the Irish-born mistress of Louis XV is very apposite – and by using them to fuse an analysis of his own political and professional status. Several versions are titled Madonna Irlanda and the whole series is a bitter meditation on the artist’s love-hate relationship with Mother Ireland and with his artistic muse. This meditation works at a whole number of levels. This Irishwoman is both beautiful and a whore. With her halo above her head she is apparently innocent in her nudity and yet she entices her followers to violence. In several versions a tricolour radiates round her seductive buttocks, in others a revolver points at her kneecap. She is both a victim, and an instigator of violence. Often the works are subtitled “boucherie à la mode irlandaise”, a pun on the French word boucher, or butcher, and the sprawling figure of Miss Murphy is marked and labelled in some of them ‘fourquarters, gigot, kneecap” etc, like an illustration of butcher’s cuts in a cookery book. She is a sexual turn-on and yet a castrater. Vitruvius’ figure of man as the measure of all things is often set into the picture, his equilibrium unbalanced as he clutches his genitals in agony. And she is shown as a living reproach to the inadequacies of the voyeur artist who frequently appears leaning into the picture, like one of Beardsley’s androgynous attendants, fixedly observing her naked charms while the cigarette he puffs is both a symbol of indifference and aimed at her like a substitute penis. (The new departure in Farrell’s work which led to this series was in fact sparked off by a commission for a self-portrait, and Farrell has continued to paint a whole series of probing and jokey self-portraits since then).

However Farrell himself has emphasised the political rather than the personal content of the Miss O’Murphy paintings. When one of these works was shown in a London exhibition which formed part of the Sense of Ireland festival in February-March 19809 it had on the canvas a statement that it would not be finished until the two Irelands are one. And in an admittedly somewhat hectic and over-dramatised interview early in 1981 Farrell claimed that these paintings so effectively attacked the political hypocrisy of the Republic’s attitudes to Irish nationalism, that although one of them was bought by the state it was never shown.10

The claim was in fact untrue. (At the time of the interview the painting, which is owned by the Municipal Gallery of Modern Art in Dublin, was on display). It demonstrates however Farrell’s sensitivity about reactions to his more political painting which he feels have been unjustly treated by Irish art critics.

“The powers-that-be in the Irish art world were good to me in my more ‘decorative’ days, they turned on me once I began to make the kind of statement they didn’t want to hear.”11

This is something of an exaggeration. While the influential Dorothy Walker says of these works “to my mind the political statement often gets in the way of the actual painting”, the equally influential Cyril Barrett sees them as marking an important though not necessarily successful stage in Farrell’s art in which he is probing and questioning his personal position.

“This may at times be embarrassing to the outside observer, but it is the stuff of which some of the greatest (as well as some of the worst) art is made. Where it is successful, we are all beneficiaries, since we are inescapably human, and can benefit from the experiences of others objectively expressed.”12

And a third commentator on this series praises the fragmentary, incomplete nature of them and of works on Northern Ireland by Rita Donagh and Adrian Hall as being “more truly contemporary” and raising more questions in the mind than the international blandness behind which many Irish artists tend to hide their opinions.

Yet in a way the very terms used by this reviewer and by Cyril Barrett, with their emphasis on personal expression and the aesthetic qualities of fragmented art, deflect attention from that very political impact which Farrell so desires to make. In the eyes of the art world and the media these works are at best an important stage in Farrell’s aesthetic development, at worst the naughty gesture of a provocative enfant terrible. The likelihood that they or other works of art discussed here will achieve any greater impact on Irish political ideology depends on a number of factors.

In the first place the general status of these artists must be borne in mind. Both Farrell and F. E. McWilliam are in the forefront of those artists who are claimed as Irish. They have an international reputation, their works sell well and their exhibitions in Ireland are generally given considerable publicity. Anyone interested in Irish art is likely to be aware of their works on the Women of Ireland theme.

In the case of F. E. McWilliam the more specific impact of those works can be given in more detail. His first troubles series was shown in Dublin, London and Belfast in 1973, the second in London and Belfast in 1976-77. All the showings were obviously successful, although the response varied at the different venues. In London the subject matter proved something of a drawback. Visitors to the first show frequently commented that the works were “too uncomfortable to live with” and press coverage was less than usual. In Dublin there were more sales than in London and the reviews were favourable. The subject matter appeared to be neither a barrier nor a bonus. In Belfast the shows were well received, probably on account of the subject matter.13 Out of the first series at least nine of the eighteen pieces were bought by private collectors and several went into public collections, including the Ulster Museum.14 Local purchases of the second series were also good. Media coverage of both exhibitions was considerable and a retrospective of F. E McWilliam’s work mounted by the Arts Council of Ireland was shown at the Ulster Museum in Belfast, the Douglas Hyde Gallery in Dublin and the Crawford Municipal Gallery in Cork in the spring and summer of 1981.15 Yet Northern Ireland artists are almost unanimous in their dislike of these works, criticising them as superficial and over-emotional. (In this criticism there may well be more than a trace of resentment at the success of an émigré artist and a feeling that he was cashing in on the troubles.)

In assessing the wider and more political impact of such works it is important to ask who owns them. Various works by Catherine McWilliams, Martin Forker and Brendan Ellis are now to be found in the collections of a prominent journalist in the Republic, a leading Fianna Fáil politician and British soldiers who have served in N. Ireland; while pieces by the Ellis brothers have also been given to friends and relations living in Catholic West Belfast. The continuing, subtle effect of these works on the perceptions of their owners have to be remembered as well as their more public impact.

This article is an excerpt from Belinda Loftus’ forthcoming Ph.D thesis for Keele University on visual imagery and the present troubles in Northern Ireland.

____

This article is reproduced from Circa Art Magazine, Issue 1: November / December 1981, pp. 9 – 13. Full issue contents here.

____