|

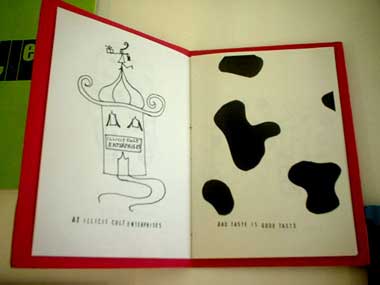

| Francis Van Maele: Cult, 2000 screenprinted handmade book, Red Fox Press, image courtesy The Workroom |

Artists with a social or political motivation for their work have frequently turned to the inexpensive multiple as a means of gaining a wider audience for the work. Books, because they have the capacity to circulate freely, are independent of any specific institutional restraints (one finds them in friends’ houses, motel rooms, railroad cars, school desks). They are low-maintenance, relatively long-lived, free-floating objects with the capacity to convey a great deal of information and serve as a vehicle to communicate far beyond the limits of an individual life or contacts.1

Alison Pilkington’s curatorial decisions in Artists Books reflect a clear respect for those independent publishers of artists’ books whose agenda is straightforwardly to publish and distribute fine, intelligent works with thoughtful, timely, and sometims provocative contents. Such works utilise the book as their form because it can be widely distributed and reproduced relatively cheaply, thus reaching a large audience and conveying content and ideas not generally reflected in mainstream publications. In her important book on the subject Johanna Drucker discusses how “the field of artists’ books…has a relation to…independent publishing."2 Drucker points out how independent publishing relates to political activism and creative freedom. Independent publishing affords artists some license to assemble their material outside of the commercial motives which determine content more restrictively within mainstream publishing.

To frame such ideas in a contemporary Irish context, Artists Books usefully alerts artists working in Dublin to the presence of independent publishers situated in Ireland such as Red Fox Press, Coracle Press, Big If Productions, and the Kids’ Own Publishing Partnership. The show demonstrates clearly that such publishers are interested in disseminating engaging, fresh, exciting material that ranges from highly visual, tactile books like Francis Van Maele’s Cult to works which exploit the social function of the book as part of its form, such as those books published by Kids’ Own Publishing Partnership.

Because of the ubiquitous nature of books and their ability to inhabit any space from bedside table to library shelf, the history of artists’ books has been inexorably bound up with notions of artworks’ existence outside of the gallery. Correspondingly, debates about artists’ books connect with other discourses that seek to question the authority of art institutions and hierarchies. Priveliging the introduction of art into everyday areas of life and celebrating the fruits of shared effort, collaboration and networking above the reification of art objects, and the cultural celebration of individual genius are themes which continually emerge in literature about artists’ books. As Drucker puts it, the field of artists’ books “emerges with many spontaneous points of origin and originality… [it] is a field in which there are underground, informal, or personal networks which allow growth to surface in a new environment, or moment, or through a chance encounter with a work, or an artist."3 Connections between artists and publishers are fundamental to the development of the artists book form, argues Marshall Weber of the Booklyn collective, and it is exciting to find an exhibition which gives the artist access to such networks;

It is crucial to form an international network and database of artists, collectors, educators, book art organizations, and collecting and exhibiting institutions in order to construct a progressive organisation that re-prioritizes literature and the arts as resources for human development and provides a critical apparatus to oppose the venal and destructive tendencies of corporate consumer culture.4

|  |

| Jacqueline Hassink: The table of power, 2000, book published in association with an exhibition of the same name, image courtesy The Workroom | |

If there is something inherently oppositional to corporate consumer culture within the development of independent publishing and artists books, it expresses itself eloquently in several works displayed in Artists Books. In Jacqueline Hassink’s The Table of Power, published in association with an exhibition of the same name in the Gallery of Photography in 2000, the book form features as a detective notebook. This work features photographs of corporate boardrooms, rendered sinister and prestigious through a heroic portraiture style. The images of empty boardrooms are a sombre reminder of how decisions are made in this society, and who makes them. The intimacy of the book form makes one feel intrusive in this instance because of the voyeuristic nature of the photographs and the way they nestle between black pages, as though intentionally hidden. The black pages in fact represent the 19 out of 40 corporations that refused to allow photography within their boardrooms, and one mistrusts the censorship inherent to this decision when leafing through the blank sections: what is concealed within these rooms that we aren’t allowed to see?

|

| Ide Moloney: Illicit Cult Enterprises, 1998, image courtesy The Workroom |

Differently barbed remarks on corporate life come with Ide Moloney’s sardonic The Philosophy of Illicit Cult Enterprises, and Ideal Candidate. In Ideal Candidate, Moloney muses about the characteristics which would signify said applicant, and lists them thus; “punctual, self-motivated, innovative, enthusiastic, highly organised, capable, team-leader, goal-orientated, conscientious, flexible, problem solver, sincere." Each characteristic is typed on its own page, beneath what looks like an idle executive scribble, and read in a sequence it does not read so much like a list, as an ironic meditation both parodying and developing the elegance of corporate boardroom speak. The Philosophy of Illicit Cult Enterprises reads as a manifesto, where, for example, “yellow is this year’s orange," and there is a critique of corporate identity built into the clever, brief text. The anonymous PR voice for Illicit Cult Enterprises confesses that “half the time I’m talking to people I’m just waiting for them to stop so I can listen to myself." In this way a narrative, a political position, an ideology, a meaning can be inferred through what seems at first to be a deceptively slim script. This is because the entire possibility of each page with its spacing, its illustrative language, and the voice implied by the text has been considered. Unlike with other books, the textual content is not privileged above the total form as being the sole communicator of meaning; it is rather included as an additional tool for communication within a complicated system of signs, indicators and conveyors that are inherent to the idea of the book, as a form. It is this consideration of form and content which differentiates the artists’ book from other kinds of book.

Artists’ books…make use of elements of production to communicate their position in a way which invests heavily in aesthetics. Manipulation of images, text, and attention to format, layout and binding all play a part in these works.5

Unlike the book about art that is produced by a large publisher under certain terms and conditions, the artists’ book has to take into account a much smaller set of marketing and distributing considerations. Smaller production costs, the means to produce one’s own books or contacts with publishers who are committed to privileging meaning and creativity above meeting mass-scale market demand, all mean that the artists’ book is a form which offers artists precisely the kind of freedom needed to actively criticise consumer culture; precisely the kind of freedom required to invent Illicit Cult Enterprises, or create a book like The Table of Power that asks difficult questions about position, wealth, and corporate decision-making.

|

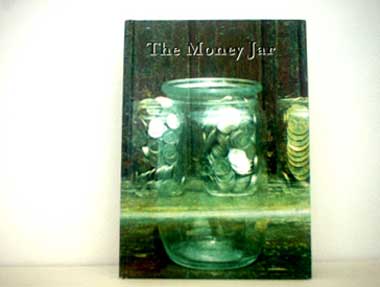

| Erica Van Horn & Simon Cutts: The Money Jar, 2002, Coracle Press, image courtesy The Workroom |

A more lyrical exploration of economics in contemporary consumer culture comes with the work of Erica Van Horn and Simon Cutts of Coracle Press. Their commemorative book The Money Jar marks the simple relationship of currency to everyday living, and references the recent switch in Ireland from the old currency to the new, remarking quietly on changes in Irish society. Van Horn and Cutts write at the front of the book about how one winter, they began to put loose change into one pound jars as a way of “saving the linings of pockets or the weight of… purses." After the quiet proclamation that “for many years the one pound jar has been the measure for making, buying and selling jam and jelly," the book goes on to explore in a series of texts and photos on gridded, greaseproof paper, referencing maths and cooking, the simple economy of the home and the weights and volumes of different denominations of pre-euro Irish money. “This book is not only a way of ending our collecting of [the coins] but one of marking their ending." It is an unsettling and simple reminder of what a globalised economy means for local trade and produce; how global changes effects localpractises. How many people still make their own jam in new, euro-signified Ireland?

|

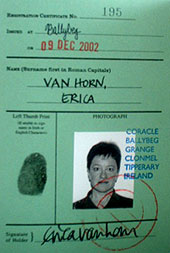

| Erica Van Horn, Some Words For Living Locally, 2002, Coracle Press, image courtesy The Workroom |

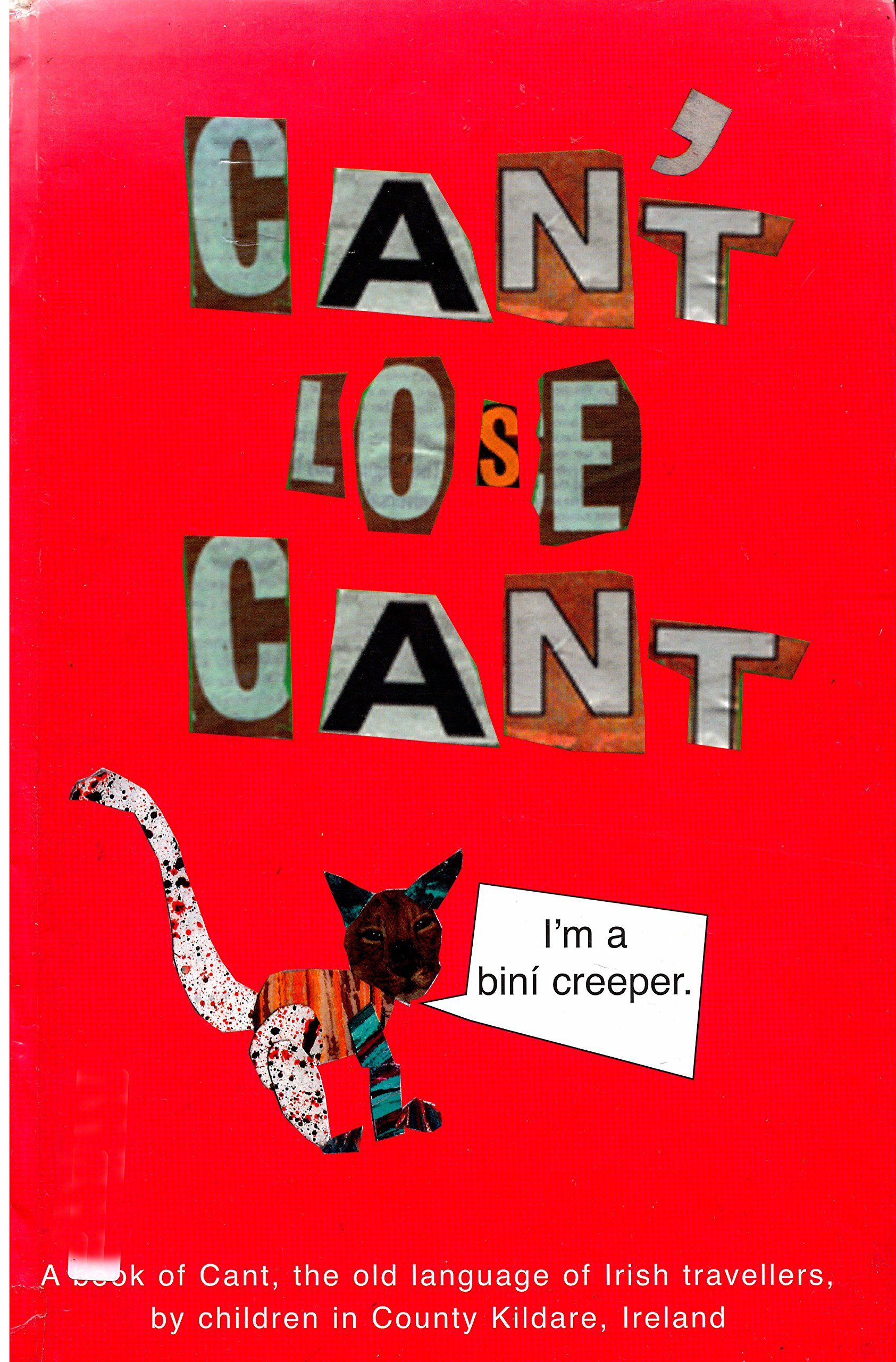

Similarly, in her piece Ideas of place: some words for living locally, Van Horn asks some interesting questions about what it means to be a non-national in Ireland. In Ideas of place, local vernacular words are presented with respective dictionary definitions. The whole book is presented in the form of a passport with a picture of Van Horn on the inside front cover, and in a kind of official, bureaucratic form on the inside back cover, we learn that the artist is American. When one considers the poignant description for the word “blow-in: (as if they will just blow out again)," which is used in local dialect to refer to people not originally born and raised locally, the total book presents a complex document about what it feels like to be a non-national living in rural Ireland. The Passport used in this context to present Van Horn as an outsider in a community, along with the language and content within the work, together seem to represent some search for inclusion, understanding, and involvement with the community which is now the artist’s locale. This is a sensitive and delicate exploration into issues that are relevant to anyone who has thought about what it means to belong somewhere, anywhere, or nowhere, and is especially relevant now as Ireland receives more and more non-nationals into its communities. A related work in the show is the book Can’t lose Cant. Described on their webpage as Unheard Voices, This is the world’s first book on the Cant traveller language, and it uses phonetic symbols to help people with the pronunciation of the words. It was produced with pupils from schools in County Kildare and is illustrated with cut-paper collage. It is visually dynamic, colourful and inviting, and provides an accessible means to explore the language of travellers which is often silenced in contemporary Irish society. The book itself functions effectively as a means to give voice to a vision and a language which would otherwise remain concealed. As a means of addressing the dissappearance of traveller culture, the book is thus incredibly proactive and the way it has been put together, visually and conceptually, gives a sense that the direct involvement with the project was empowering, fun and informative for the children who got to work on it.

|

| Kids Own Publishing, Can’t Lose Cant, 2004, image courtesy The Workroom |

The mission statement on the Kids’ Own Publishing Partnership website indicates a revised approach to the way children learn, and expresses a dedication to developing inclusive and participatory teaching methods. Kids’ Own Publishing Partnership use the suitability of the book form as a class-room aid for helping children articulate their own visions and stories, and take part in the creation of their own educational material. Children are encouraged to “engage… in the creative process of working together towards a shared outcome," and Kids’ Own are committed to evaluating the book’s efficacy as a learning tool which can “extend children’s experience as readers and writers and illustrators." By including children in the creation of books, they effectively challenge prevailing ideas about who creates educational material and for whom; their manifesto is one which seeks to empower others, and their way of working uses the construction of books as the process by which to do this. Not only do Kids’ Own Publishing tackle important issues through the creation of individual books; their work, analysed more generally, asks important questions about the assumptions we hold regardng children and education. Their vision is one in which children are seen and are heard, and this is arguably still a radical stance to take in terms of challenging existing authority structures or restructuring education. Arguably, it represents a set of issues which find historical resonance within the field of artists’ books, which is in itself caught up with a history that seeks to redefine authority structures, and give voice to visions which would otherwise not gain any exposure.

With their direct, practical approach to tackling children’s societal issues like bullying, integration and racism, Kids’ Own Publishing Partnership is not disimilar in ethos to the ideas expressed in the Booklyn Artists’ Alliance website. Marshall Weber writes that “in this war torn world of environmental and political crisis it is the responsibility of those with the means (and privilege) of cultural production and distribution to preserve and develop the full spectrum of creative practice and to assist in imagining and enacting solutions to the worlds problems."6 Although not necessarily declaring themselves as such, or asserting strong political identities, the books published by Coracle, Mermaid Turbulence, Ide Moloney, Red Fox Press and other individuals and organisations represented within the exhibition Artists Books, do seem to exist in a cultural space where artists are free to speak out – inside and outside of galleries – on important issues, like racism, economics, politics, and education. The examples of the book form in the exhibition, Artists Books, demonstrate not only what a book can be, but also what it can do. Form and content extend the medium beyond its physicality and into its social function, and that is surely the most effective utilisation of what Drucker has termed “the 20th-century artform par excellence."7

Felicity Ford is an artist and writer currently based in Killiney. She is currently involved with the installation of her sound-works in the end of year DLIADT graduation showcase, and is working with Arts and Theatre collective Spacecraft on their current production, Bleeding the System.

Links:

Footnotes:

1. Drucker, Johanna, “The ArtistsÕ Book as Idea and Form," The Century of Artists’ Books, New York City, GranaryBooks, 1995, pg 8

2. Ibid.

3. Ibid.

4. Weber, Marshall, “An Essay on Booklyn style," Artists’ Book Yearbook 2003-2005, editor Sarah Bodman, Bristol, Great Britain, Impact Press at the Centre for Fine Press Research, University of West England, 2003

5. Drucker, Johanna, “The ArtistsÕ Book as Idea and Form," The Century of Artists’ Books, New York City, GranaryBooks, 1995, pg 8

6. Weber, Marshall, Op-cit.

7. Drucker, Johanna, Op-cit.