As part of Circa’s on-going ‘Archive Project Editor’ award, Bangkok-based commissioner Dr. Brian Curtin presents a photo-essay by Amirahvelda Priyono. Full details of the project are here. Continuing Possibility of Hope was prompted by an interview with exiled Chilean artist René Castro from a 1989 edition of Circa.1 The interview discusses the local conditions of making political art and across a range of geographical contexts: between Belfast, Latin America, the US, and Palestine. Working outwards from artworks, and back through history, Priyono presents two major artists in Southeast Asia, FX Harsono (Indonesia) and Manit Sriwanichpoom (Thailand) in relation to Castro’s earlier works. The photo-essay is a gentle prod for readers to consider the conventions of political art from different times and contexts – how similarities and differences can be drawn to think through the local and the universal. And, in this respect, keep alive the specifics of regional politics as a means of acknowledging the state of our current world.

Content warning: some of the images below are upsetting.

Presenting political art provides challenges including sensitivity to local issues. That is, how issues are intersected by the regional and historical. Also, critique can provoke risks (for example, censorship or offence). But both are the means of strong perspectives or arguments that should help us understand history in the present. And photography, I believe, is particularly notable here.

Below I probe these ideas through René Castro, FX Harsono, Manit Sriwanichpoom. All are of different nationalities and from different backgrounds and times but comparable in their sense of political opposition and use of photography, including reproduction, and the archive as intrinsic to their practices.

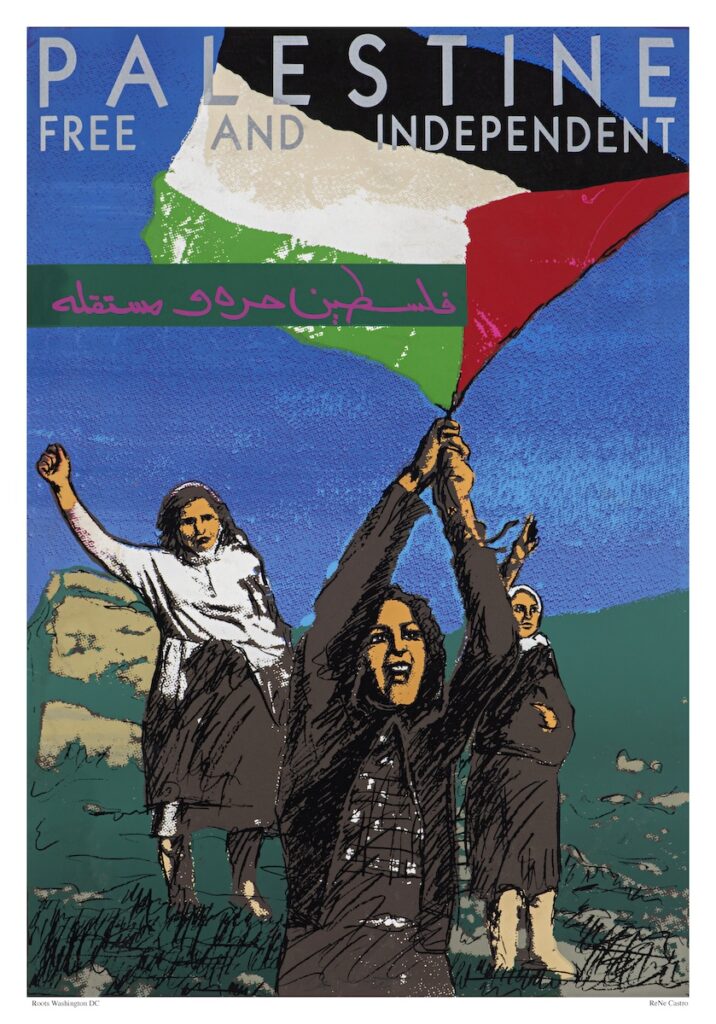

Palestine Free and Independent shows three women standing in a green field under the blue sky. One of them flies a Palestinian flag as part of showing the fight against Israel. As Palestine’s major language is Arabic, Castro also translated the title into Arabic script.

By showing Castro’s previous work about solidarity with Palestine, we can also see how the archive is important for understanding continuing conflicts – or the sheer fact of their continuation.

Sin título (Primera intifada) is a montage, two photos of Gaza’s street and sky with electricity cables and two photos of severely injured boys in a hospital bed. The work includes handwriting by the artist to express his concern about the Israeli conflicts between 1987 and 1993.

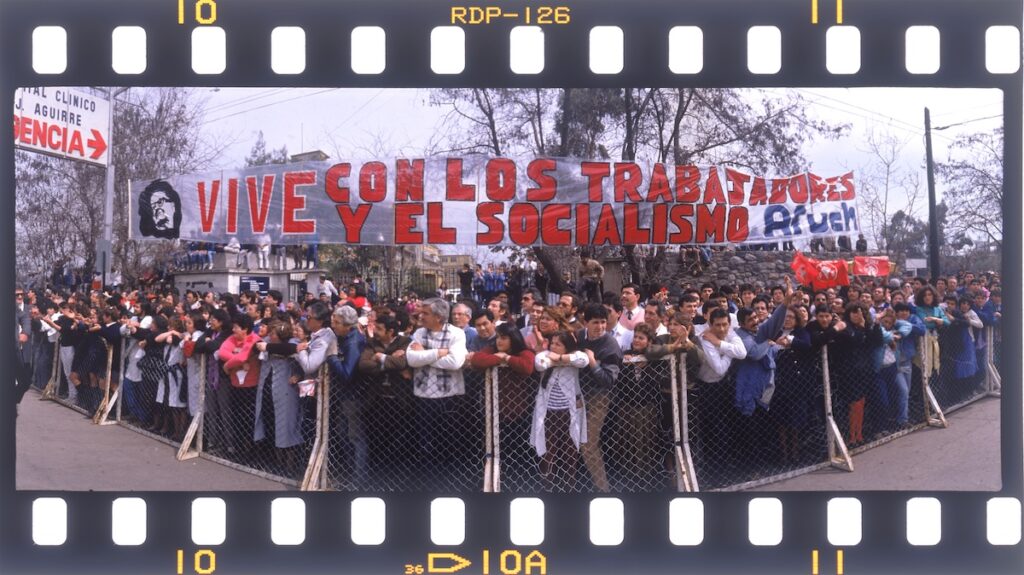

In his hometown of Santiago, Chile, Castro took photographs of President Salvador Allende’s (1970-1973) funeral ceremony just before a military dictatorship ruled the country. The images portray the grieving public.

Sin título (de la serie Funeral oficial de Salvador Allende) shows women of various ages standing behind a metal fence. Some hold posters, in Spanish, with Allende’s portrait and also red roses to express their condolences. The colours are vibrant tones of navy blue, red, and white which represent the national flag of Chile. The photograph holds patriotic and nationalist nuances but just before the premiership of General Augusto Pinochet (1973-1990) led the country into dark times.

This photograph is panoramic, 180 degrees. Castro chose this method because of the long banner across the road; during the funeral ceremony of Allende. The banner was made of plastic, with a written statement in a big red letters that translates as ‘Live with the Workers and Socialism’ from Spanish, and shows people’s concern and solidarity just before Pinochet’s government emerged.

In Southeast Asia, Indonesia and Thailand have produced comparable artists: FX Harsono and Manit Sriwanichpoom. FX Harsono was born from a multicultural background of Chinese and Javanese and has worked as a contemporary artist for over 40 years. His works have reflected on political conflicts in Indonesia, especially during the May Riots in 1998.2 This conflict happened during the second presidency of the young republic, President Suharto (1968-1998).

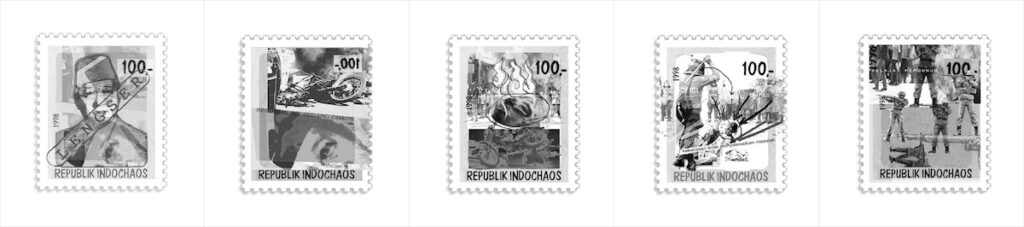

Republik Indochaos (1998) is a series of photo-etchings with various photojournalist scenes of 1998’s May Riots that ended President Suharto’s regime. This artworks were created as stamps to play on the uniqueness of regions, countries, and cultures.

FX’s works are always research-based and include references from historical documents and photographs. He relies on the archive to experiment with his works.

“I am not a photographer. I make art using photography. Photography is a tool to capture everything. This is real. If I put a found image inside the gallery, this becomes real. So I use the photograph like a found object. I do not want to produce something artistic. I do not want to produce an artistic thing.”3

This reveals that photographs with a strong historical narrative do not need much modification to explain further.

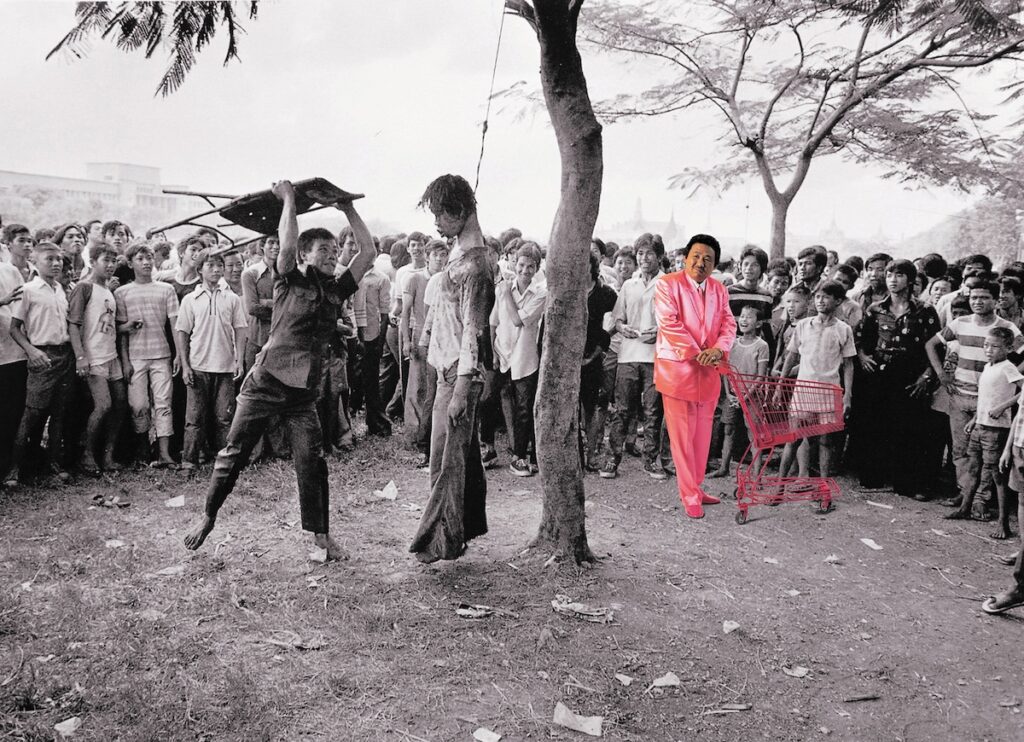

Manit Sriwanichpoom is a Thai artist who created an iconic figure titled ‘Pink Man’ in 1997 in order to criticise consumerism and political indifference in contemporary Thai society. Pink is interpreted as vulgar and associated with excess: shocking and loud. Here I include Manit’s work Horror in Pink #1 in which he used a photograph of a major incident in Thailand known as the October Massacre in 1976.4

In selecting a suitable model for the ‘Pink Man,’ Manit chose Sompong Thawee, a theatre-man. Manit believed that Sompong’s presence as an already iconic figure would attract the public’s attention, and this could be shifted to historical events. His facial expressions could also be proxies for our attitudes: deadpan, intimidating, and careless depending on the situation or context in the photograph. Unlike Harsono, Manit uses a different understanding of history by putting an icon of the present with a different expression inside the photograph.

This is from a sub-series of Pink Man (1997-). Here he uses an example of photojournalism from brutal political conflict in Thailand during 1976 and in black and white. By placing the pink figure inside the photographs, the artist provokes people’s response to a grave incident that shaped Thailand today. The figure’s presence is relaxed and seemingly without conscience; the artwork critiquing how consumerism may force people to forget recent history.

The pink man’s presence in this photograph critiques the prevalence of consumerism over education and democracy. The child with a scout uniform can be interpreted as someone who always obeys rules and has little space to express their thoughts.

Justus M. van der Kroef (1978-1979) has highlighted “state of war and siege” as the common political pattern for Thailand and Indonesia where citizens against oppressive political decisions are also fighting for freedom of expression; and irrespective of their different political systems, constitutional monarchy and republic.5 Or, these countries share responses to political oppression.

As Manit identifies the matter:

“Politics is an idea. The idea cannot manifest itself. It is like air. You need art to clothe the idea, so that people can see it (…) Activism cannot activate without art.”6