Amanda Dunsmore, Keeper

Dublin City Gallery The Hugh Lane, 10 April – 22 July 2018

It’s unusual to observe well-known political faces on screen and for them not to utter a word. That’s exactly what Amanda Dunsmore presents to us in Keeper. John Hume, former leader of the SDLP, and David (now Lord) Trimble, former leader of the Ulster Unionist Party, are presented in 20-minute, looped, video portraits on huge screens that sit alone in different rooms. There is a similar video portrait of Mairead Corrigan Maguire, co-founder of the Peace People and co-recipient of the 1976 Nobel Peace Prize. Somehow it does not appear so unusual to see Mairead on screen but not speaking. A reflection on how we are socialised to often see women silent, or silenced, while men do all the talking? She doesn’t face the camera but instead looks to her right and upwards and occasionally looks as if about to speak; or is it a smile? Another behaviour women are often socialised to do – smile – especially before making a statement that males present might find challenging.

By contrast, John Hume appears very relaxed and comfortable, looking slightly to his left and downwards, as if reading notes, or taking a moment of reflection. David Trimble, however, stares straight ahead, almost directly into the camera lens. He holds himself very erect; very rigid. Both he and Hume appear at times as if about to speak. Their mouths and chins twitch momentarily. Probably it takes some degree of energy on their part to suppress the instinct to automatically speak once a camera is placed in front of them.

Amanda approaches her work from a belief that there is “… a generational memory and understanding which is fading from the collective history in Northern Ireland, Ireland, and Britain” and in the body of artworks that comprise Keeper she is trying to “preserve memories and reiterate people’s actions through portraiture.”

Keeper has its origins in Billy’s Museum (2004) and the latter forms part of the exhibition. That work arose from the period Amanda spent as writer in residence in Long Kesh/Maze Prison. I wasn’t there at the time, thankfully, having left some years previously. However, her role there was a fitting conclusion to more than a decade of focus upon creative and artistic works by republican prisoners, myself included.

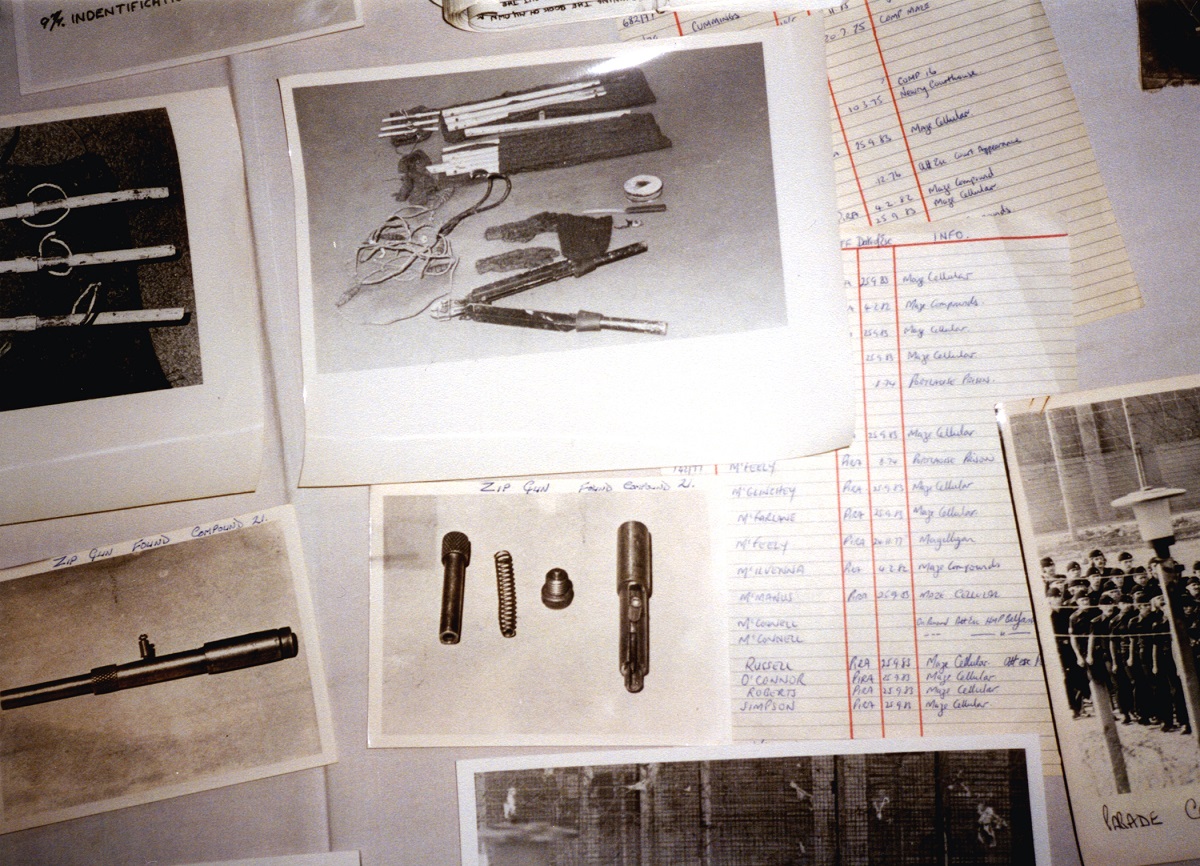

Our motto in developing and encouraging the arts in prison was that we should ‘write our own history’. Unknown to us at the time was that a prison officer, Billy Hull, over a 15-year period was curating his own secret museum within the prison from ‘illicit’ items seized by warders during searches. His interest in doing so was to preserve history and his actions were in defiance of orders of his superiors to destroy the items. It’s ironic that whilst we (republican prisoners) were officially categorised as ‘non-conforming’ prisoners, Billy was simultaneously flouting the prison authority.

It was close to the end of Amanda’s residency in the prison (and the closure of the prison in July 2000 with the release of all political prisoners following the signing of the Good Friday Agreement) that Billy revealed his ‘collection’ to her. A more liberal-minded governor, by then aware of the collection, had given Billy permission to gather the artefacts together in the old prison laundry. Amanda filmed the exhibition and it resulted in the work called Billy’s Museum.

That work became the starting point for Keeper, which expands the theme of portraiture and its role in social and political life and further reflects on the formal and informal processes through which memory and history are made. It also reveals the threads and interconnections beneath the surface but usually invisible at the time. For instance, Billy’s Museum contains a photograph of David Irvine, then a loyalist prisoner but later the leader of the Progressive Unionist Party (PUP) and signatory to the Good Friday Agreement. Although there is no photo of Gerry Adams in the collection, he too also spent several years in the prison, just a few hundred yards from David Irvine, and years later, as President of Sinn Féin, was a signatory to the Good Friday Agreement. As Billy correctly says, “It’s part of our history.” It shows us where we have come from.

Keeper has evolved and expanded over twenty years and each manifestation of it is unique to the exhibition context and gallery space. Other elements in the current exhibition include portraits of Edward Carson and John Redmond by Sir John Lavery. As with Hume and Trimble in later decades, both played a central (and politically opposing) role in Irish politics at the turn of the 20th century. In 2018 we’re still engaging with those same issues. Lavery completed the portraits on the condition – agreed with Carson and Redmond – that they would be presented to the gallery to hang side by side. They do so in Keeper and in presenting a visual correlation between them and the video portraits of Hume and Trimble, Amanda has kept to Lavery’s stipulation of visual equality.

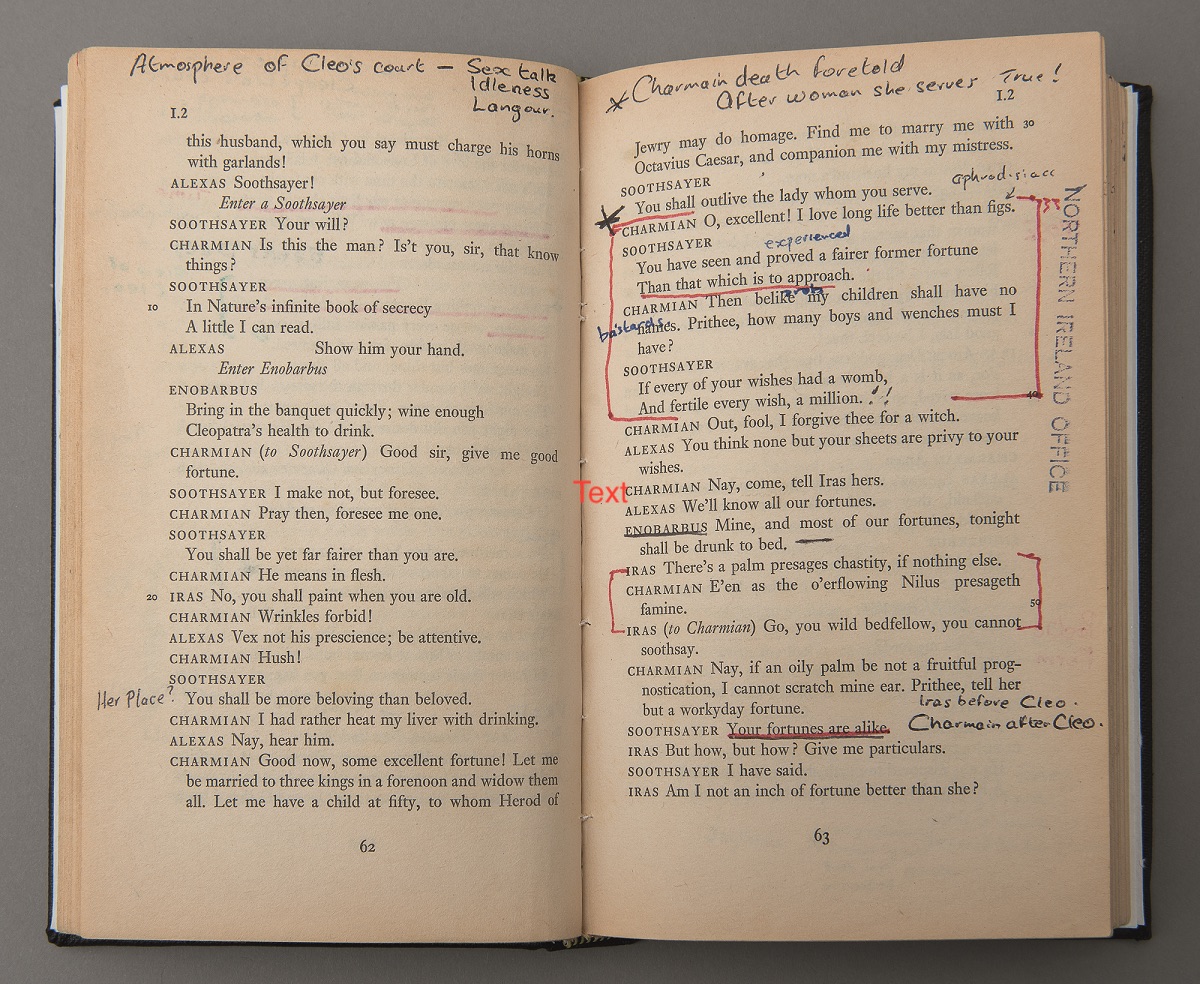

The other artworks that complete Keeper are: The People’s Portraits: 1899-1918; one hundred framed black and white anonymous, photographic portraits from Millisle’s (another prison in the north of Ireland) prisoner photographic collection; and, The Soldier and the Queen; spoken text and words (depicted on three monitors) sourced from Shakespeare’s play Antony and Cleopatra, a book Amanda found abandoned on the floor of an education hut in Long Kesh.

In the catalogue accompanying the exhibition Amanda writes, “Time loops. Processes circle.” I agree. And Keeper very accurately reflects that. A former prison officer at Long Kesh who later became a security guard at Stormont where the Northern Ireland Assembly meets, when it’s functioning, was once asked by a journalist what it felt like to see so many former republican prisoners now attending Stormont as elected MLAs. He replied, “I now open the doors for those I once locked behind them.”

The ‘keeper’, and the ‘kept’ change with the passing of time.