In Between the acts, Virginia Woolf’s posthumously published novel, a play is performed before a boisterous audience in a small village. Throughout its staging the performance is continually interrupted by the protagonists’ thoughts and interpretations. This interplay between a work of art and one’s response to it forms a central theme in Sunday night, Aleana Egan’s exhibition at Temple Bar Gallery. Woolf’s work has a particular significance, with one of the sculptures, Lanes and chooses, taking its title from this play within a novel. Egan’s sculptures represent the final stage in a complex artistic process, one which begins by interpreting the world around her, including the literature she reads, in terms of her own experiences, internalising this response and, finally, reformulating it in her own work.

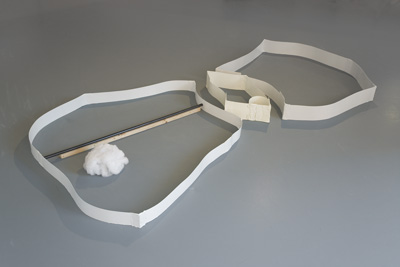

This carefully curated selection of Egan’s work focuses on pieces from her recent practice and balances complex assemblages with more simple steel forms. The relationship between the sculptures and their surroundings forms an important influence on our apprehension of the work. The first object encountered, Lanes and chooses, establishes the centrality of Woolf’s work as an artistic influence. The largest piece, Laid flat, shrugwall, positioned against a corner of the gallery, commands attention. An unassuming form, the steel Understudy stands lightly across the room, its shadow testament to an initially mysterious title. The harness-style pieces, Laid flat and Lobby looking toward balcony, lie around a corner waiting to be encountered in a slightly more closed space – one conducive to deeper contemplation. Their titles suggest an architectural perspective; should we be looking into or out of the work for this view? The pieces pick up Egan’s preoccupation with architecture, seen in earlier works, but abstract it further, absorbing it into her ever-developing formal language.

The exhibition comprises six sculptures – a collection of steel twists, cardboard folds and puddles of cement. Draping forms resembling harnesses are affixed to walls while other free-standing pieces rise in graceful curves; their delicate forms belie the rough-hewn nature of their constituent materials. Their titles are often taken from books or other ‘found’ texts and form a useful entry point to more opaque pieces.

One of her sculptures has been installed outside the National Maritime Museum in Dún Laoghaire to coincide with Sunday night. Originally sited on the banks of Glasgow’s River Clyde, its title, War atlas yachting and nautical cuttings, was taken from a 1942 Church of Ireland copybook found by the artist. Its form mimics that of a doodle on the front of this book. Both title and location activate significances across many levels; on the one hand its siting continues its maritime connotations and further reinforces the artist’s interest in her old home on Haigh Terrace, an interest which appears throughout her work.¹ Yet the site is significant not only because of the museum’s seafaring connotations, but also because of its original incarnation as a Church of Ireland church. The private moment of discovering an old book becomes transformed in its re-imagining as an artwork. The piece’s meaning is then further complicated by its transposition to a public site. Egan combines a vast range of sources in her sculpture to create imaginative new cross-references and, in the process, enriches the object of inspiration beyond the capacities of its original context. Perhaps the physical effort required to produce such work – taping, painting, setting, moulding and welding – is required to render fleeting sensations and experiences more permanent, to transfigure a highly personal, internal world into a more communicative form.

Any survey of Egan’s work will reveal an oeuvre preoccupied with literary reference.² A text accompanies the exhibition which comprises a series of literary snippets (the provenance of which is not entirely clear). These simple forms have complex implications. Some lines are copied from F Scott Fitzgerald’s Tender is the night, others from Woolf’s The Waves and To the lighthouse, and there are even some lines from the song I have confidence in me, performed in The Sound of music. Fragments of classic literary fiction have been selected and reconstituted by being placed within a larger context. This effacement of the original author and interweaving with Egan’s other personal selections serve to foreground the creative impulse of the artist over that of the writers. Between the acts‘ cacophony of voices seek to make meaning through language, through articulating their opinions. The fragmented narratives of modernist literature appear to have inspired in Egan a reflection on subjectivities. References to journeys, encounters, textures and feelings, thoughts and dreams produce a splintered moment, one caught between a reverie and more immediate sights and sounds. These lines indicate a search for meaning and understanding. They query how one can ever know truth given that perceptions change and judgements are never fixed.

On deeper consideration of this and the works’ titles, the sculptures come to hum with a range and depth of allusion not apparent from an initial survey of the room. The text redirects us to the sculptures, reminding us that language is an unreilable vehicle for sentiment which becomes transformed in the moment of reformulation into words. Egan’s work reflects the modernists’ despair at the inadequacies of human communication. Perhaps, Egan suggests, it is better to transfer those sensations into sculptures, to skip the transfigurative moment of articulation and produce work that is solid, mute and immutable. Her forms articulate that which is beyond words. Personal readings, memories of landscapes, people, interactions are reconfigured into abstract form. Though their abstraction is diminished by gently inviting titles, they are never so prescriptive as to render them obvious. One can never claim for certain what Egan intends. This is part of the sculpture’s magic and mystique.

Following the lines “lanes and chooses," Between the acts‘ characters ponder the nature of time. The title of the novel suggests an inbetween time, that gap between experiencing life in the moment and pausing to reflect upon it. This resonates strongly with the texts and sculptures of Sunday night, whose very title captures that time spent elsewhere in the mind with premonitions of the week ahead.

Process is very important in Egan’s work and the moment of creative reformulation ‘between the acts’ is often as important as the final product. In Sunday night she shows how private preoccupations can have wider significance, invoking a wistful mood that is both deeply personal yet has resonance for anyone who has ever dreaded Monday morning. It is the strength of Egan’s work that she draws upon a personal range of reference to produce universal work that does not overpower the viewer with her particular preoccupations, but rather tempts us quietly into imagining that which lies beyond words.

Already well established on the international stage, Sunday night, Egan’s first solo show in Dublin, is sure to further cement her reputation in her hometown.

Ciara Moloney is a writer based in Dublin.