|

| Albert Oehlen: Ohne Titel (Untitled), 1994, oil on canvas, 240 x 200 cm; courtesy the artist / Whitechapel |

It is becoming increasingly less common to walk into a gallery to see large-scale painting of the kind which predominated during the 1980s. The excessive gesture no longer has the impact it once did and, unless posited as a statement of irony, it has gone the way of the shoulder pad. That is not to say that it does not exist, but simply that its impact as pure mark-making has been compromised.

Hand in hand with this style of painting comes a poised and considered irreverence for the medium itself. Marks and gestures proliferate and clamour, one over the other. The effect is of a badly weathered billboard, the fractured history of layered images revealed forming a fortuitous abstraction. Walking into the ground floor exhibition space at the Whitechapel Art Gallery, we are confronted with a tasty selection of just such billboard-scale paintings from the late ’80s and early ’90s. Every colour imaginable seems to be here, in some corner or almost hidden under the surface. Such is the force of the bombardment of the surface of the canvas with pigment that it is as if Oehlen is attempting to invent a new colour.

|

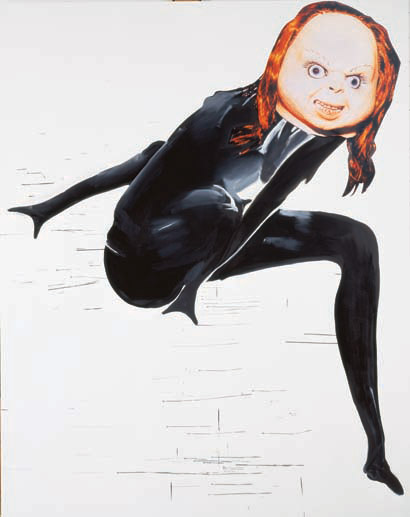

| Albert Oehlen: Chucky, 2005, acrylic, oil and paper on canvas, 290 x 230 cm; private collection; courtesy Whitechapel |

The ’80s and early ’90s are bristling with gestures like the ones we see in Oehlen’s canvases of this period. The conceit of the time seems to be: the grander the gesture, the fresher the product. This could be said not just of painting, but also of the ambitious sculptural projects of Jeff Koons or Damien Hirst. The perception remains today that painting was the medium which came to be under greatest theoretical and philosophical attack at the time. In fact, the well documented crisis which developed in this period manifested itself not just within painting itself, but in the complete abandonment of the medium by a whole assembly of artists, of which Koons and Hirst are among the best known. Oehlen’s work from this period, however, appears to be doing the same thing without abandoning the medium. In what seems now like an act of over-compensation, it posits itself as inflated, puffed up and larger than it really is, like an animal under attack.

|

| Albert Oehlen: Auf (der Strasse) schreiben (Writing [on the street]), 2000, oil on canvas, 240 x 240 cm; ArtVest Limited; courtesy Whitechapel |

A dramatic increase in scale does not automatically transform the operation of the painted surface. With Oehlen’s work of this period we get a sense of a self-conscious artist working within a self-conscious project. Whether or not this was the impact of this type of painting at the time it first appeared is difficult to recall; however, the much-popularized, even mythologized, embattlement of painting as a project is apparent in these works. Here we find some of the oldest visual references available. From architectural columns to the human skull, the codified iconography of traditional painting is woven into the surface.

|

| Albert Oehlen: Gerüstbau (Scaffolding), 2000, oil on canvas, 240 x 240 cm; The Frank Cohen Collection; courtesy Whitechapel |

The mainly grey paintings upstairs tell a different story. Oehlen claims that the more recent grey paintings were motivated by a desire to deprive himself, and thus the viewer, of colour in order to sharpen the desire for it. The surface here is more refined, as much in painted gesture and incident as in colour. The contrast with the earlier works on the ground floor is stark. These works are slower, more mature, and perhaps for this reason more successful. The earlier paintings, despite their apparent abandon, are actually more compositionally unified and self-contained, perhaps more complete. The grey works have no centre and seem to meander well beyond their edges. They are less self-contained. They exist with us naturally and do not try to demonstrate or display. This is painting which appears to have left the preoccupations of the ’80s and ’90s behind. It is no longer concerned with its appearance. Here, scale and treatment each work to the benefit of the other.

|

| Albert Oehlen: Gezeichnete Hunde (Drawn Dogs), 2005, oil on canvas, 210 x 260 cm; The Cranford Collection, London; courtesy Whitechapel |

Amidst these grey works are some other, more recent paintings, which employ collaged elements. These, as with all the work in this show, are large, almost award ceremony scale. There is a cursory attempt to combine the collaged and painted elements, using paint, but the effect, whether intentional or not, resembles a lazy school project. It is hard to tell exactly the statement that is being made about the medium of paint here. While the earlier works seem to be motivated by knowingness, these pieces never entirely commit. As collage they are unconvincing in their artless illusionism, and as possible pastiche they look outdated and awkward, even ‘uncool’ next to a host of less well established artists working today. Even next to a contemporary of Oehlen such as Martin Kippenberger, they lack the same committed rebelliousness and experimentation.

Irreverence for a medium does not preclude knowledge of the medium and how it works. These late works seem to forfeit in impact that which they gain in sheer scale. It is hard not to wonder what they would look like if they were smaller, more intimate, more modest.

Robbie O’Halloran is an artist and writer on art.