A Painting Framed by a Biennale

38th EVA International, Ireland’s Biennial, 14 April – 8 July 2018

As long as I’ve known of it, EVA has always sparked much debate amongst the visual art community here in Limerick for which it is a divisive talking point. Outside Limerick, particularly on social media, it may seem that the consensus over EVA is overwhelmingly positive and enthusiastic. But inside the studios, at exhibition openings, in the college, in the bars and all the places where artists congregate you get a real sense of just how complicated feelings towards the biennial are.

Money and resources allocated to EVA, or the lack of, depending on whose argument you are listening to, are always a hot topic down here. For example, in the past, contentious rumours have circulated describing situations where EVA had ferried distinguished guests in taxis to and from Dublin Airport to Limerick, while invigilators (many of whom are artists and art students) worked for very little or nothing at all. Whether true or not, and in conjunction with the limited resources and opportunities artists can avail of in general in Limerick, these stories create tensions and polarise opinion before the artworks are even installed.

But it is perhaps the actual art that EVA presents that is most fiercely contested within the local art community. Limerick is a funny one in terms of prevailing tastes and trends for contemporary art. In my experience and opinion there seems to be a disproportionate appetite for art that embodies sentimental, melancholic, handmade, gestural or modernist traits. This is apparent in many practices based here, and also in the exhibition programme at Limerick City Gallery of Art, which under the relatively new directorship of Úna McCarthy seems to me to be shifting from a varied programme to one that largely reflects and promotes such sensibilities. These tastes are at odds with the art of a typical EVA, which at times has also been guilty of disproportionately representing very specific trends. Trends that call to mind every cliché associated with contemporary or conceptual art and international biennials: impenetrable installations, videos galore, text everywhere etc. It is out of this set of opposing approaches that we get a robust conflict of opinion within the Limerick art community on EVA.

My immediate thoughts, after my first visit to this edition of EVA, were that whether by accident or design this year’s curator, Inti Guerrero, might well have made an exhibition that offers something to each contrasting position on EVA in Limerick and beyond. Even before this, rewinding to the call-out for submissions from artists and to another EVA rumour, this time an encouraging one: word on the ground was that early on the curator made an appeal to the EVA board that the entry fee for submissions be either abolished or lowered. This may explain the reduced fee from € 25 in previous call-outs to € 10 for this one. If true, this is an acknowledgment of the uncertain conditions artists have to operate within, and it certainly helped smooth out any anti-EVA sentiment with regards to fairness: GOOD START!

Nearly every EVA has either an artwork or a building that defines it in the collective memory of its audience. The most obvious of these being Luc Deleu’s monumental sculpture made from nine shipping containers for Construction X in 1994. This work was re-presented in 2012 to mark EVA’s transition from an annual exhibition to an international biennial format. The work that will surely define this edition is, unusually for EVA, a painting, and an old one at that. Seàn Keating’s painting from the late 1920s Night’s Candles Are Burnt Out, is the nucleus to the exhibition as a whole, both physically and thematically. Hanging alongside other paintings by Keating also depicting the construction of the Ardnacrusha Power Station, it is positioned just inside the entrance at the centre of Limerick City Gallery of Art, itself the traditional centre of EVA. So, here we have a work the curator himself regards as the departure point for conceiving the exhibition, explicitly positioned to demonstrate its very significance. It is from here that this year’s EVA unpacks itself.

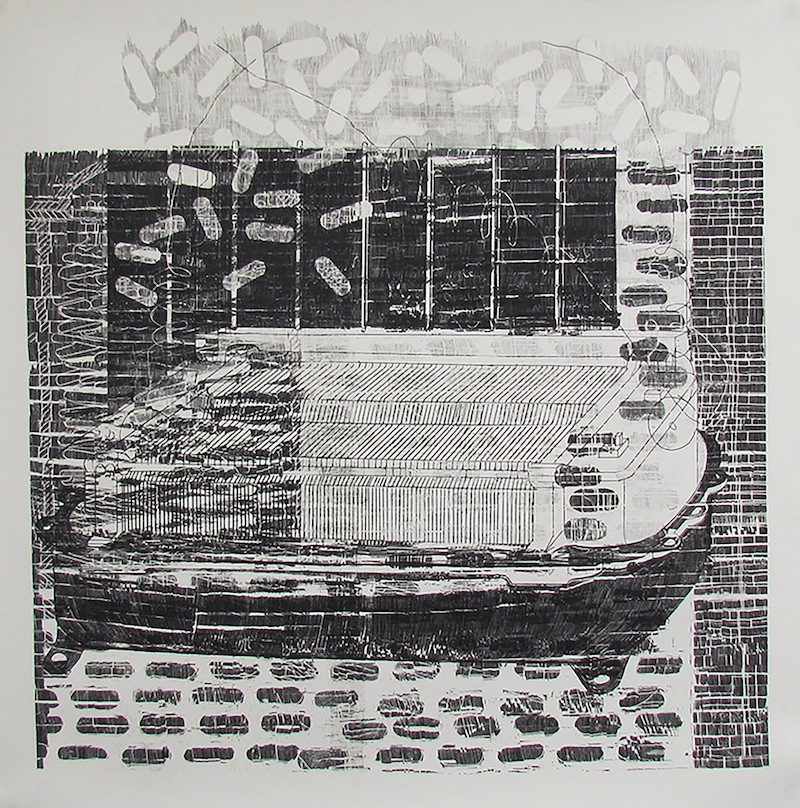

The Keating paintings documenting the construction of the hydroelectrical station mark a pivotal moment within the Irish state, themes of change, transition, technology and nationhood are easily drawn from them and they are to be found in many of the artworks throughout the Gallery and elsewhere in EVA. In fact the connection to the Keating paintings is really quite literal at times. Uchechukwu James-Iroha’s absorbing series of photographs, Power and Powers (2012), in the adjoining room for instance explore relationships between political power and electrical power distribution in Nigeria. More artworks in other adjoining rooms directly interrogate and reference the physical, political or social dynamics of dams and other national super constructions. A beautifully composed image of the Panama flag flaps defiantly on a screen as part of José Castrellón’s installation Palo Enceba’o (2014-16), an artwork that meditates on Martyr’s Day commemorating the 1964 riots over the Canal Zone. Julie Merriman’s superb drawings in the same room comment on drawing itself and the capacity of evolving forms of technology and design to transform the built environment. Urban transformation is also addressed by Steven Cohen in another nearby room: Chandelier (2001) is an engrossing video documenting his provocative performance and the reaction to it by residents in a neighbourhood in Johannesburg with many homeless people. The work thinks through processes of gentrification and social cleansing. Quite literal links between artworks are again present in this room, with the motif of the chandelier recurring in Lee Bul’s suspended sculpture State of Reflection (2016), and Gonzalo Fuenmayor’s tall Charcoal drawing Apocalypse XXI (2017).

These literal links and the essayistic accessibility of the artworks and ideas seem to have gone down well with many visitors I have spoken to so far, even the EVA sceptics. You get the sense that this accessibility of ideas is really important and central to the curatorial form of the exhibition. Information about works is very present and explanatory in the wall panels and accompanying publications. The inclusion of an unusual number of paintings and drawings for an EVA, most of which are in LCGA, also seems appreciated and popular. Another prominent figure in 20th century Irish art featured is Mainie Jellett. Her paintings, like Keatings’, reflect changing times in the early formed Irish state, but also demonstrate a connection to deep-rooted sensibilities and values before these transitional moments. Modernist concerns seemed secondary for many Irish artists in the early twentieth century. As European painting was retreating into its own flatness, Irish artists like Keating did engage in self-reflexive processes, but did so with the aim of exploring identity politics and nationalism, with landscape painting becoming an important theme. Jellett however embraced the new and changing painting languages being explored by modern painters on the continent. Yet at the same time Catholic and Celtic symbolism informed the work, making them particularly Irish and rooted in the past as much as connected to a modern moment. Kevin Mooney’s paintings, hanging in yet another adjoining room to the Keating suite, evoke a similar sensibility, being bold, stylish and contemporary, and yet at the same time also connected to something ancient and primal. Upstairs in the Gallery more paintings and a different set of connections are to be found: Ian Wieczorek’s and Claire Halpin’s paintings share the mezzanine and themes related to territory and borders. The conflict related to the Northern Irish border is described in Rita Duffy paintings next door, again works of historical significance albeit more recent in the Irish painting canon. There is even a painterly feel to much of the work in other media throughout the gallery. John Duncan’s series of photographs documenting the huge bonfire constructions in Belfast and their social setting are beautifully and richly textured. And reflecting on 9/11 Alejandro González Iñárritu’s 11’09”01 September 11, (2002) picks apart and rearranges sound, footage and components of film in a way that evokes painting or collage more than video.

While artists and artworks are quite concentrated together at LCGA, the presentations at EVA’s other main venue, Cleeve’s Condensed Milk Factory, are far more diffused. The different spaces at the huge site of the former factory accommodate a series of solo presentations by individual artists, at times monumental in scale. Sanja Iveković’s Lady Rosa of Luxembourg (2001) overlooks the expansive open enclosure of the site. This is a close contender to Keating’s iconic painting for the defining image of this year’s EVA. Documents illustrating the contentions caused by this beautiful golden statue of a pregnant symbol shimmering high above its column are presented in a nearby room. Similar dynamics are echoed in this current moment in Ireland where images are being wielded and contested in relation to gender politics and reproductive laws. In the battleground of the upcoming referendum on abortion we have seen murals removed, sensationalist signage and in EVA the Artists’ Campaign to Repeal the Eighth Amendment group present their contribution of visuals and archives to the debate. Again this is a nice link back to the pivotal Keating painting bringing up the ongoing yearning of artists to document but also initiate change.

The biggest warehouse spaces at the Cleeve’s site are used to full effect. Alone in one of these massive spaces, a mesmerising large scale virtual simulation of a solar power plant, Solar Reserve (Tonopah, Nevada) (2014) by John Gerrard stops you in your tracks. Another nod to the Keating painting and symbols of technological progress. Other vast rooms house single works or artists. Sam Keogh’s immersive installation and performance Integrated Mystery House (2018) projects the viewer into the future, but a future where progress has been stunted perhaps? Here again, like so many of the works throughout EVA, a painterly or collage-like quality is present in its making. The same can be said about Isabel Nolan’s exhibit in the next room, which is seductively rich in form and colour and impressively framed by the architecture and ambience of the building. One of the attractive features of EVA historically is that it opens up to the public these different architectural textures around Limerick. Nearly every edition includes a new venue, and often presents a rare opportunity for much of the public to view the art in unexpected places and gain access to these buildings. This year the exhibition extends throughout the city to The Limerick Clothing Factory on Lord Edward Street, 6 Pery Square as well as the Hunt Museum. The form the exhibition takes in each venue feels very different to the next, but the themes and the links to Keating’s painting weave them together. And lastly, in a move I suspect is more relevant to marketing the biennial outside Limerick, than it is to the ideas and artworks that characterise it, EVA also expands further afield to IMMA in Dublin.

Sean Keating’s Night’s Candles Are Burnt Out reflects on the aspirations of the newly-formed Irish state to be modern and outward-looking. However the painting acknowledges through allegory the conflicting, complicated dynamics and the tug-and-pull between the past and the future enmeshed in such hope. In a way the very concept of an event like EVA is a project or vehicle for Limerick to define, transform and position itself as a modern, outward and future facing city. Such intentions have equal significance in cultural terms to the ambitions of the Irish state to distribute electrical power through the construction of the Ardnacrusha Power Station in the 1920s. And, as the painting suggests, aspirations of that scale generate fierce debates and tensions. This is because there is so much at stake in the idea of shaping the future, even through the instrument of an event like EVA. Every member of the visual art community in Limerick, whether practitioner or enthusiast is a stakeholder in that future, which explains the vigour each person brings to the EVA debate. Starting by looking backwards, in a quite diplomatic fashion I think, this year’s edition takes into account a multitude of distinctive engagements between artists and their worlds, offering food for thought to most perspectives. And, really interestingly, Inti Guerrero’s exhibition proposes a model for the biennial that draws directly from the regional and local contexts of Limerick and frames them universally in a way I have not seen done in EVA before.