“A work of art does not fill a prescribed space. It invents the space which it fills. There is no space for the unwritten poem, only for the written." [1]

The exhibition of William McKeown’s work at the Irish Museum of Modern Art (IMMA) begins problematically, opening at the top of the staircase from the main foyer of the museum. It is frustrating in the first major museum show of an artist for the introductory text to appear on a wall where it is impossible to read, accompanied by a gallery plan, photocopied askew on A3 sheets, with full information provided in the case of only some of the works. While these matters are trivial, it would be naïve to imagine that they don’t affect the first impression of any visitor and they call into question the status of what should be an important stepping stone for the contextualisation of McKeown’s work.

The landing is used as the first room of the exhibition and the two main formats of the paintings which are continued in the rest of the show are laid out here – two small paintings (each 43 x43 cm) on each end wall punctuate the display, while on the back wall the small and large (182 x 168cm) formats are interspersed. Essentially, they are all variations on blocks of colour – instantly reminiscent of Mark Rothko’s work [2] – and seeming to operate as a series of paintings. Washes of creamy and yellow oil paint are built up across the deep beige of unprimed stretched linen. The technique is very much revealed in the finished surface as the variation in shades (from the lemon yellow tinges of Untitled (1) [3] to the bluer grey tones of Untitled (5)) glows through each thinly applied layer. The texture of the large works is grittier, where a drier brush has grated against the textile’s façade, leaving behind a rubbed and bobbled fabric. McKeown’s initial training in textiles adds resonance to the contribution of the otherwise negligible surface patterns of the fabric, as he states: “I want the sense that the oil is in the linen, rather than on the surface." [4]

Around the edges of each of these paintings (and all the paintings in the exhibition) a line of dark brown serves as a loosely daubed frame to contain the sweeping build-up of colour within. This also recharges the vigorous tonality of each shade of cream through the immediate contrast. Despite this form of enlivening containment, these paintings do seem to spill out regardless onto the grey wall around them and, hung as they are a foot above the dirty vinyl floor, they lead the eye outwards in each direction, coming at the viewer almost from underneath. The subtlety of variation within them is certainly what lends them their depth, and this space at the top of the stairs is oddly successful at positioning them in an open space, with benches provided to spend time absorbing the overall effect. It is worth noting, however, that the benches were provided by the Douglas Hyde Gallery and Kerlin Gallery – a small but significant detail, given the importance of lingering: “Each painting creates a pause between his work and the time you spend with it." [5]

Moving through into the main wing dedicated to this exhibition (also serving as a corridor through to the In Praise of shadows exhibition) the long gallery is windowed on one side and is otherwise given over to Waiting for the corncrake (2008), a new multi-part work consisting of 30 watercolours on paper. The architecture of the inner courtyard of the museum pervades this difficult space and presenting this work here, opposite and almost mirroring the windows as in Versailles [6], is the greatest success of the exhibition. The pale rectangles of grey, framed by a thin pencil line, barely distinguishable from the white paper on which they are applied, seem to glow with different shades following the patterns of light from the windows. Pinned to the grey wall only by nails at the top corners, they curl under at the bottom, as if freshly ripped from the artist’s sketchbook, ready to move with the breeze of movement through the room just as their content seems to reverberate with the changing light. They successfully respond to the challenges of the space and transform it with a feeling of transience and a strong sense of place. The reproduction in the catalogue [7] reduces the group into a static tonal exercise in colour, which in this gallery setting is the least perceptible attribute of the series.

The corridor is flanked by an interconnecting series of galleries where the remaining 27 works struggle in claustrophobic spaces flooded with bright light from the south-facing windows. Uniformly hung with four or five of the small/ large work combinations, with one framed coloured pencil drawing set between the windows, the sequence seems an attempt to create a dialogue between the works. Perhaps this would function more successfully if the incidental patterns within and across each of the works were not half-obliterated by the streaming winter sun. Their arrangement falls somewhere between acknowledgement of the space (with the careful positioning of the pale pencil drawings) and complete indifference to the architecture (as before, the large works end one foot from the floor, although in these inner rooms the skirting boards split the connection to the gallery floor, resulting in an awkward gap).

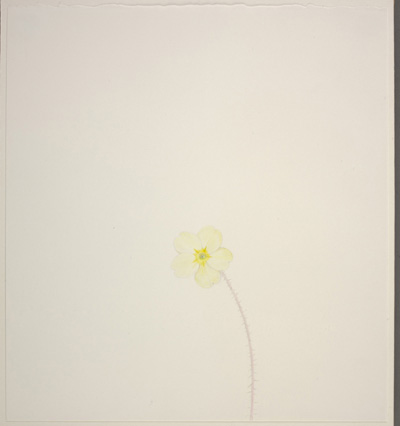

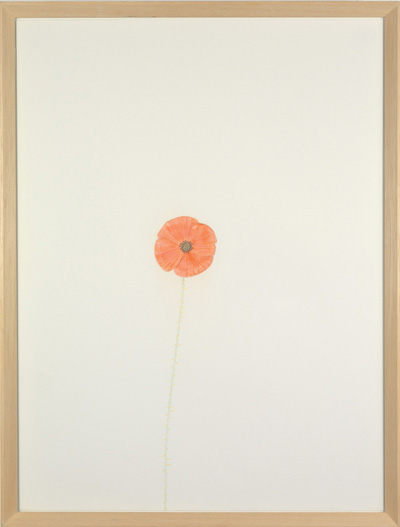

The older pencil drawings detail single flowers drawn with simplicity and disingenuously framed in pale beige wood frames. Each domestic flower appears to grow up from the base of the frame into the void of the bleached paper, impressively intricate in form while maintaining a childlike simplicity in composition. Grounding the seemingly abstract paintings in a geographical and temporal reality, they connect the blocks of grey, blue and yellow to the land. While the paintings compete with the natural light of the room, these drawings demand intimate inspection and satisfy the curiosity evoked by the blanker paintings.

If the works in the corridor and landing enmesh the viewer within their composition (“a concave space instead of a convex space…you can enter the painting as you are and it embraces you" [8]) then the dense packing of work into the remaining regimented rooms excludes us, precluding a deeper understanding of the artist’s aim and curiously echoing the corncrake narrative in the exhibition catalogue:

“We used to lure them to mirrors when we were boys and watch them fight with their own reflections." [9]

The individual works selected provide the reflective space and depth of meaning that their installation lacks. When considered slowly and with air around them it is possible to see in the painted surfaces “what was there before does not really disappear; it just sinks down a little further beneath the surface. Irish culture is sedimentary, with layers of experience and emotion folded on top of each other." [10]

Mai Blount