A paradigm shift may be personal, cultural or global and may engender fear as long-standing established norms evaporate. History is littered with such significant changes in science, religion, technology, art and politics. The 126 Gallery based in Galway presented its membership with the challenge of responding to this theme and as a result fourteen artists were selected for the exhibition at the RHA Gallery in Dublin.

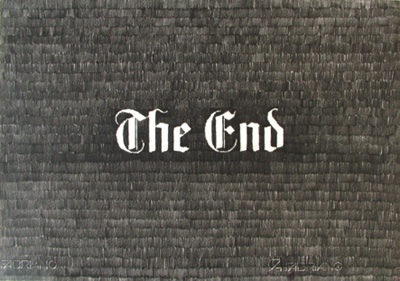

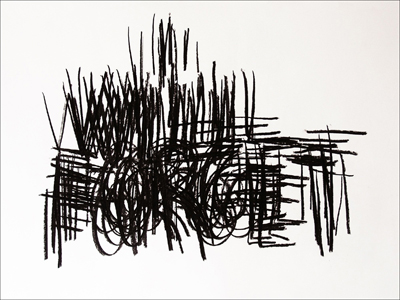

Within the history of entertainment Vaudeville theatres were once a popular social activity until the allure and invention of the talking picture. To accommodate this new demand the theatres placed silver screens where stage scenery once stood; the curtains still opened and closed maintaining the theatrical formality. When film moved from cinema to home viewing, VHS became the standard, consumers traded a shared experience for personal ownership. Breda Lynch‘s short animated film entitled The end depicts the closing titles of a movie, and the simple but well exacted pencil drawings of interference and glitches that were once the bugbear of many video makers have become the central focus. Accompanied by a soundtrack performed by violinist Marja Tuhkanen, the artist has deliberately remixed the music ‘This is the end …’ by The Doors to obscure its familiarity. The removal of memory and the dark degradation of the images reflects upon a fragile moment when a recorded image, a recollection, could be lost through the deterioration of VHS. Inevitably the desire to technologically eradicate anomalies in favour of perfect, crisp, pristine pictures led to the demise of VHS, but what we fail to appreciate is that mistakes can be just as important and necessary as the pursuit of a flawless image. Overlooking Lynch’s animation, Dominic Thorpe’s charcoal drawing repeatedly exclaims the phrase ‘I Will Forget’ in angry black marks obsessively overlaid on top of one another. The act of repetition usually helps to reinforce memory, but here it is contradictorily obscure, its original intention becoming a visual oxymoron.

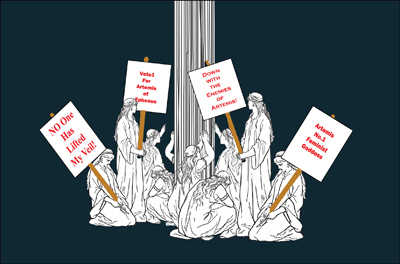

A trend, political movement, fashion style or religion can only survive and prosper through the collective memory and actions of its followers. Angela Darby references the Christian belief of the ‘Virgin Birth’ in the aptly titled God has no favourites. The small Giclée prints beckon us into the cult of the pagan goddess Artemis of Ephesus. Here the artist controversially insinuates that Christianity plagiarised and assimilated traits of this goddess to suit their deification of Mary, the mother of Jesus. Are Darby’s intentions inflammatory for reasons of sensationalism, or perhaps the artist wishes to understand and expel the falsehood of the ‘virgin’ fairytale?

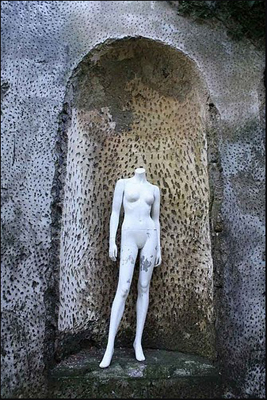

When one icon falls a substitute takes its place, absorbing the past to validate its presence, assuring its position in history. The digital photograph by David Finn, Mannequin in alcove has an arresting quality to it; the alcove’s walls are puckered with what could be mistaken as bullet-hole pockmarks, the battles scars from a revolutionary uprising or struggle. Surprisingly the location of the photograph is the grounds of the late-eighteenth-century manor house of Ardfry in Co. Galway. A damaged and soiled white headless mannequin stands in the alcove, parodying the self-importance once associated with a religious statue of significance. The mannequin is the perfect consumer idol, a frozen female icon, society’s deification to materialism. The Scottish-based artist Cathy Wilkes’ use of shop dummies in her installations draws similar connotations to Finn’s piece.

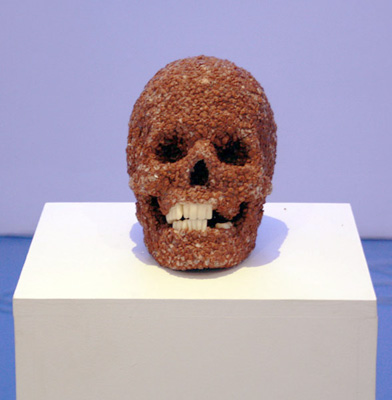

Coco pop skull by Padraig Robinson laughs in the face of art as expensive commodity, possibly taunting the likes of Hirst and Koons who have traded their art souls for the trappings of celebrity. Fiona Chambers skilfully combines traditional crafts with randomly sourced images from the Web to create cross-stitch designs packaged with coloured thread. Applying chance to the systematic binary code that underlies all digital technologies, the artist raises interesting questions. Through Google, the superior virtual version of reference books such as the Encyclopaedia Britannica, we have instant access to billions of bytes of data; it’s up to us to stitch together the information available, into meaningful knowledge, instead of being entangled in a web of casual associations.

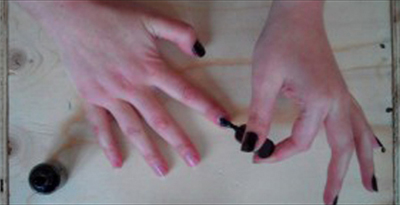

At the gallery’s entrance Kathryn Maguire’s text piece quotes the Greek Philosopher Heraclitus (c. 500BC) of Ephesus. His statement ‘the only constant is change’ is laser cut from vinyl acrylic mirror, a material commonly used in advertising and shop displays. The mirrored surface of the static words paradoxically ensures the reflected ‘content’ alters each time the viewer shifts their gaze or the public move around the gallery. An order rises to exact a change only to be toppled by another. James Merrigan’s The devil of the little place plays on American social insecurities, with a back projection of the White House viewed through what appears to be a sniper’s telescopic lens. On a rickety wooden slatted bed a small video monitor plays footage of fingernails being painted black. Once regarded as an act of rebellion, the colour-coded statement has been assimilated into mainstream culture along with tattoos and piercings. The video sound track lists American presidents’ names, though in a reference to ‘back-masking’ the words are played backwards. During the eighties and nineties ‘back masking’ became an obsession with right-wing American evangelists. They claimed that playing rock-music backwards revealed hidden Satanic messages which subliminally corrupted the listener.

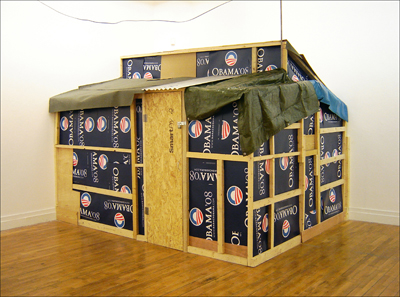

With A shanty we can believe in Jim Ricks also chooses to comment on American society. Constructed in the corner of the gallery stands a makeshift shelter decked with Obama presidential election placards. When two social classes form, one an aspiration of the other, they remain caught in a symbiotic clinch. The work seems to question what real difference the president will make to the underprivileged where his predecessors have failed.

The works mentioned above, and including Kevin Mooney’s small cityscapes along with Paul Murnahan’s Somehow you knew this was coming, avoided obvious clichés and had a connective quality to them. Mooney physically slices into his futuristic urban landscapes, disrupting the illusion of a dream-like Utopia and in the process places the viewer back in the ‘now’.

Many of the works capture the liminal stage in the ‘ritual of change’; the end of one thing is the beginning of something new. Video killed the radio star is simultaneously retrospective and visionary, a reflection of the past and contemplation on the future. The speed of advancement in technology has transformed our approach to communication, opening new futures in which to assess the past. It is a testament to the curators that the diverse elements of this exhibition stand together so cohesively, though they are aided by the quality of responses garnered from the artists.

Helen MaCormack is an art historian based in Edinburgh.