The exhibition begs the question: can there be an image of the world? What would it look like? The stakes are high: the power of understanding through the imagination and, beyond that, an urge for something more; perhaps an aspiration, a gesture towards the truth. The curator seeks a model of practice based on values and Shinnors Scholar Mary Conlon finds it in ‘Multiplicity’, a lecture by Italo Calvino. The show is part of a bigger project which adopts all Calvino’s 1985 Harvard lectures later collected in Six Memos of the Next Millenium (1993). Conlon has asked five artists to interpret ‘Multiplicity’ their way. The titles framing the other five Memos and the focus of more exhibitions are equally vast: ‘Lightness’, Quickness’, ‘Exactitude’, ‘Visibility’, ‘Consistency’.

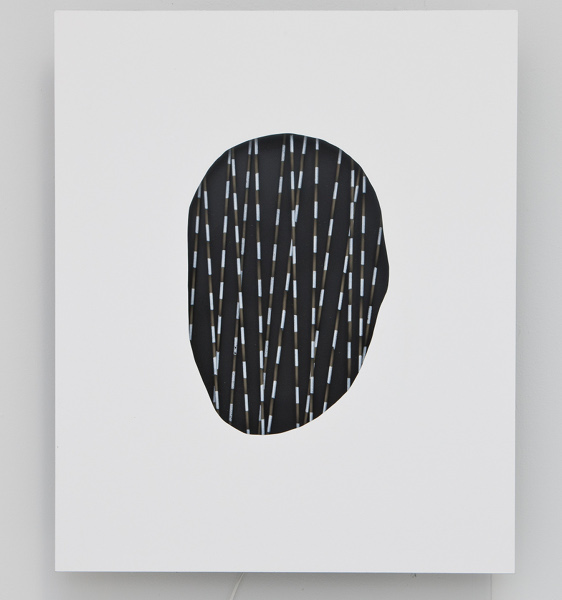

But let me try to be a purist first. I have reached the gallery, Occupy Space; I recognise the curator. Caught unawares, she is a good sport and agrees to show me round her world of multiplicity, a curator’s interpretation, and what five artists make of it. Illuminated, Juan Fontanive’s kinetic sculpture, catches my eye. Dotted lines cross the empty cut-out of a head against a dark background inside a box frame. The workings of the mind, the synapses that click when we understand? I can’t say, but I like that fact that I am not looking at a dematerialized form. His other works are also intriguing sculpture machines; they’re not on show, but one fits the medieval notion of Ramon Llull’s combinatory logic, in its sets of twirling cards spinning on wheels. Llull used wheels too in his manuscripts, with letters signifying concepts, to help you prove God really does exist and is a Christian. I worry that the photograph of Illuminated will look stock still and fail to convey the incessant movement I see before me and its blur. But no, that’s not a problem.

The Horse’s Mouths is a quirky installation by Helen Horgan which features the inside of her mind as she explores personal associations along the way and manifests them into three-dimensional symbols of a sort I don’t understand, unless… but there is a story somewhere, associations, maybe, as intricate as the combination of light, water, model ships floating, while a huge comma hangs on the nearby wall, a trace of the text that populates her other work.

More than just a humorous footnote, James Merrigan’s short film Goth-Head features the customary double-take of the banal: a suspended tripod hanging in the middle of the frame in a garden backdrop, punctuated by a zombie voice in synch with its subtitles (of the words cheerleaders utter in countries where they live). My Mother is a Fish is also tongue-in-cheek: a coffin size box stands on its head with the title in caps running down the corrugated lid; two chairs and a minute’s audio of William Faulkner’s novel As I lay Dying which, truth be told, I have forgotten. All I can remember is that Faulkner was fierce, almost physical, with language.

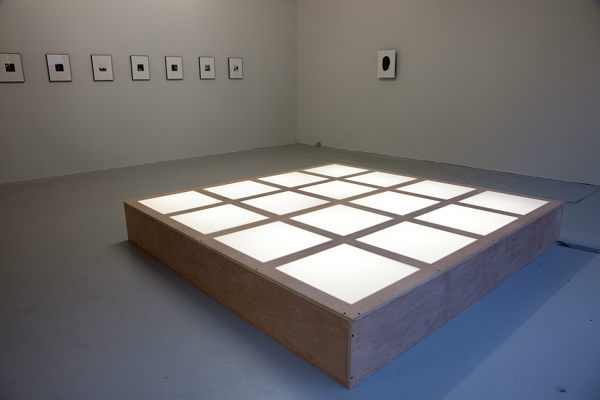

Michael Murphy’s The Taste of Dancing on our Tongues is a small-scale dance floor. “It’s minimalist,” says Conlon. I agree. But I can only taste the right angles with my eyes, not the exhilaration of movement, and why should I?

Dana Gentile is based in Brooklyn some of the time. More than to the larger-format colour ones, I am drawn to her row of black-and-white photographs printed on silver gelatin paper. Maybe because nowadays, for some reason, most artists print big, so it is nice that these are small icons of a lost age of half-forgotten details, time stilled in recollection, some square Rolleiflex format, maybe taken with a Rolleiflex camera.

What I find fascinating about the exhibition is not the single work, it is the text and that writing is at its inception. People often say that the work must speak for itself. I have just tried to do that. Here it speaks back to the text in some kind of visual form.

Calvino champions the multiplicity of the author. There’s traffic in that head, Fontanive. To borrow a concept from twelfth-century Platonism, his attention sweeps across from the microcosm of the word, the sentence, its infinite associations, to the macrocosm of the novel. Multiplicity can take the form of multiple selves, of an instability of being, of how memory and time can collapse or expand, as in one writer Calvino chooses not to mention, though his work is central to this idea. I am thinking of Umberto Eco’s Open Work written years and years earlier, in which Eco applies complexity theory to works of art, including Robbe-Grillet’s rambling novels and Cage’s music.

All right, so there’s a dichotomy between chaos and order, between logic and imagination, and Calvino tries to recompose it into a unity of sorts where mathematics provides precision applied to the imagination. His ideal writer wanders across an imaginary space exploring inner worlds. Peering into the unknown of now, Calvino’s paradigm, his matrix of writing or of art, is a combination of precision, structure, method and language, so that each text could contain a model of a universe or, in philosophical terms, a Kantian transcendental, in other words, an ordering principle of reality, yes, call it ‘a world’.

Calvino’s own writing is also (after a postwar phase of literary neorealism) filtered by logical leaps of fancy that take the reader into the unknown, unmapped territory or the ten beginnings of his novel If on a Winter’s Night, or its alternative endings. By then, his neighbours in Paris, the French philosophers Calvino does not to mention, had already published most of their work or were dead (Foucault). Deleuze had already attacked the One in the name of the Many (of multiplicity); Derrida had challenged logocentrism in everything he ever wrote (except Spectres of Marx); Foucault likewise, for whom the idea of power as One Bad Thing was nonsense, because power is everywhere. Here’s the very beginning of Deleuze and Guattari’s A Thousand Plateaus (1969): “The two of us wrote Anti-Oedipus together, since each of us was several, there was quite a crowd”. These people were all fed up with structuralism and dazzled by chaos theory, by the mathematics of problematics which Porphyry’s hierarchical tree structure (for organising concepts) and mathematical axioms simplify more than they explain. They are the spectre’s spectres and haunt Calvino’s multiplicity.

Despite his heroes, Gadda, Musil, Mann, or Perec, and the (apparently) formless authorless text, however incomplete, Calvino’s paradigm of writing is all-encompassing in its reach and forms a unity. In his matrix, there is no postmodern multiplicity, because ultimately Calvino recomposes the complexity of the world into the work. Language and logic are assigned the task of weaving together the great branches of learning into a vision of the world, no matter how complex, how multi-faceted and it is a revisited concept of the encyclopedia, however complex, not Eco’s Open Work, that serves as a model. And there’s no relativism, there are still values.

Does Trompe le Monde cohere? Do these voices form a pattern? Is that what a group show is, a pattern? Time was, when shows were full of clever text to make a point. But here the text (over twenty pages of a lecture on multiplicity) is absent or at least invisible. But is it? Am I going to argue that there are multiple exhibitions: if Calvino’s text is a spectral presence, not an absence, then it has a say in what is on display? Calvino was a brilliant short-story writer and an editor for most of his life. OK. Once he made one big mistake: he wrote back to Primo Levi to say, sorry, I am going to turn down your manuscript (If This is a Man). Levi survived his guilt for surviving the Shoah, got the book published in the end and went on to write the magisterial The Damned and the Saved. So words, and the spectral presence of the text I had not read yet (which lives in a large folder on the table by the door of Occupy Space) and indeed I have never seen before, are inevitably part of this visit and can easily spiral out of control. The show is a multiple response to Calvino’s idea of multiplicity. Once you have read this text, I would argue that you slowly begin to see his spectral show and his spectral writers.