|

| Greaney and Taylor: Useless beauty, 2007; photo / courtesy the author |

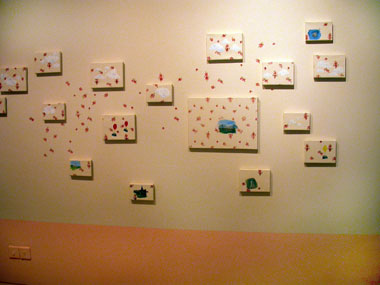

Do you believe in monsters? Throughout all the pieces in this show there is at least the suggestion of something monstrous, in the three time repetition of the staring eyes of Manet’s piper, colour photocopied into giant pixels, and mounted, clad in different candy colours each time like an unknown soldier, changing uniforms and sides for the same or different battles, then blown to bits, a fragmented body, still playing his tune in Useless beauty by artists Greaney and Taylor. Something monstrous certainly in Carly McNulty’s germolene-pink walls of the third room, the recollection of being an adolescent girl, the scattered pink blossom on white squares, reminiscent of teenage wallpaper of the 1980s and of spring. A sense of something burgeoning, bursting to get out of these walls, and dream-like memories, perhaps of dreams of the future, daydreams, scale the walls on otherwise blank canvases, fears and hopes, the Mary Poppins black taxi cabs held up by birthday-party multicolour balloons, hints of sex, future or real, a self that like the canvases jutting out of the walls, is trying to break out, body as architecture. Memories of childhood, already lost, and hopes and dreams of the future, idealised, already memorialised, lost somehow, nostalgic in picture-postcard style. The germolene walls conjuring an imaginary smell, of scratched knees and first-aid schoolrooms, hospitals, obsessive cleanliness, order, polished shoes, patent leather, girls’ annuals, problem pages, dirty novels with well-thumbed middles, a bedroom without a bed. For the female viewer you are thrown back on yourself, a mirror, to your own adolescence, to that complicated world of secrets and anxious daydreams.

|

| Carly McNulty: Untitled, 2007; photo / courtesy the author |

|

| Carly McNulty: Untitled (detail), 2007; photo / courtesy the author |

A monster too in the manic cardboard city of Maggie Madden’s Devour, hundreds of discarded product boxes joining to form a cityscape, a built-up coastline, of interconnecting small boxes, pharmaceutical packets, cigarettes, like the view from a landing plane at one of those seaside airports, impressive, and still you can make out some of the adverts, like the rooftop ads already coming into being, or a vision of advertising taken just one stage further, all over the cityscape, advertising Self-tan Super-soft Romance Triumph bra Multipurpose Glue Life’s a glass and a half full Triple Cool Stripe After Eights Eleven o’Clock Tea Smoking causes ageing of the skin Find out about your baby’s life before birth Electrolux pet lover and then a small red packet addressed to Mark Grehan, curator of the show, c/o the Galway Arts Centre. Another mirror. And then more boxes, some packets of raisins outside the window which send the viewer on a fruitless search for more development outside other windows. The perspective and scale changes as the boxes climb the wall above. Instead of aerial distant view, these large open boxes appear to be a zoom in, a close up of one fancy apartment with a sea view.

|

| Maggie Madden: Devour, 2007; photo / courtesy the author |

Monster perhaps in the form of River god (crude) by Noel Brennan, the most overt reference to a monster of the deep, the good monster, or something from the other side of the Unconscious. River god is in fact a piece of furniture / architecture, a high table, with a green top, perhaps for card games, a dog-eared lighter green corner. The river is reduced metonymically into parts, its bare essentials. Green table top for the river bank, reflective steel sheet for the river, tar for the god. The sheet of steel, set at an angle, reflects the legs of the table, multiplying them and transforming them into the base of a ladder. The furniture sprouts potential other forms. The Gate, also by Brennan, consists of wooden slats slotted into an arch on the stairs, seeming to hope to keep these monsters at bay, contained within the gallery. The arch, the fairytale keeper, through which the viewer has to pass by, in order to enter this realm of monsters. A Gate suggesting that they are locked up most of the time, in our minds, in our Unconscious.

|

| Noel Brennan: River god (crude), 2007; photo / courtesy the author |

And this is like a fantasy voyage, the viewer knight with sword come to slay the monsters, or come to see how ferocious they are. And we go further up, hoping perhaps to find a damsel in distress in need of saving at the top of the gallery, and instead we find as in all good psychological stories, a mirror. The War journal by Carl Doran awaits us, not of war at all, but rough sketches, inked drawings modelled on war journals as a method of documentation, which depict the making of the works and of this show, one called Glue gun, another Mark curating . However, later in the evening after a couple of glasses of wine, the war in these journals suddenly revealed itself to me. Drawings on tight-lined brown paper with figures sketched on top – suddenly those very same figures were imprisoned by the lines, like a Guantánamo story. Figures crouched over, standing, all behind lines. Even the drawings of the boxes for Devour began to shapeshift into graves, endless soldiers’ graves.

|

| Carl Doran: The War journal (detail), 2007; photo / courtesy the author |

And then, there is Comfort, another piece, put together by everyone in the gallery, simply an invitation to inflate a bed, lie on it and read a copy of the provided bed-time book, Relational aesthetics, the biggest monster of all, or yet another mirror.

Susan Thomson is an artist and writer, currently pursuing an MA in Visual Arts Practices at DLIADT.