SS: Born in Armagh, educated in Belfast – what higher degrees have you graduated from?

SC: Born in Co Armagh, graduated in Classics from Trinity College Dublin, and then took the Advanced Diploma at the (then) Ulster Polytechnic, Art and Design Centre.

SS: After graduation you set up your art practice straight away? I recall that you started in London, then moved to Bath, Bristol and Prague. Beside the genius loci, was it the internet that allowed you that mobility?

SC: I started showing work in Dublin while an undergraduate, at first a three-man show and then a one-man show in the time between TCD and Belfast. I then exhibited much less as I undertook commissions for publishers, moving to London, then Bath, and now dividing my time between Bristol and Prague.

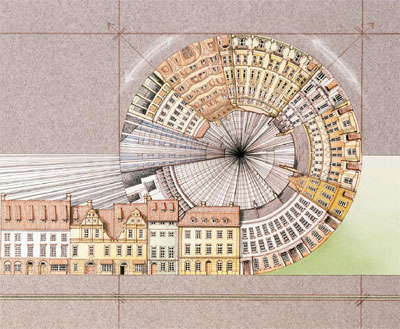

SS: Your images were always very particular. I focus on two characteristics: high-key light and exactitude.

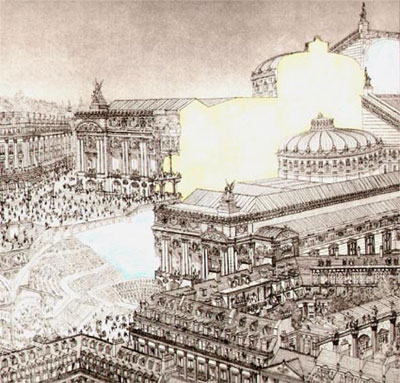

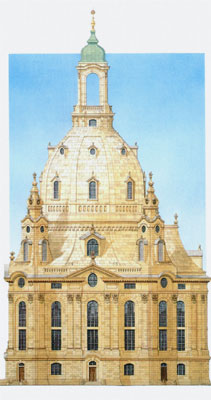

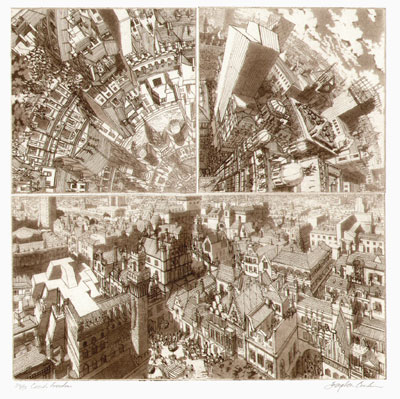

These aesthetic values appeared from the early stages. You never abandon them. My art-historical bias links you to Vermeer for treatment of light and V Hollar for representation of architecture – both baroque masters. Moreover, you love baroque cities. What in Prague or Dresden attracts you most?

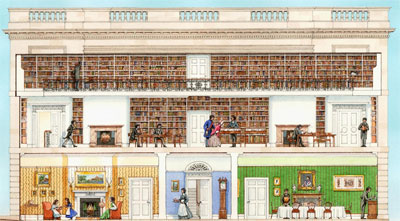

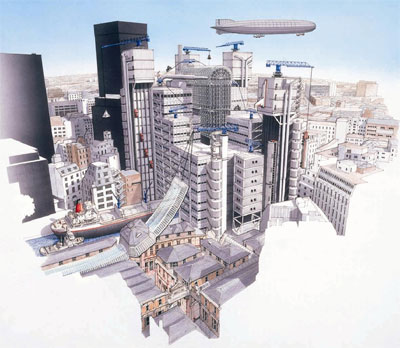

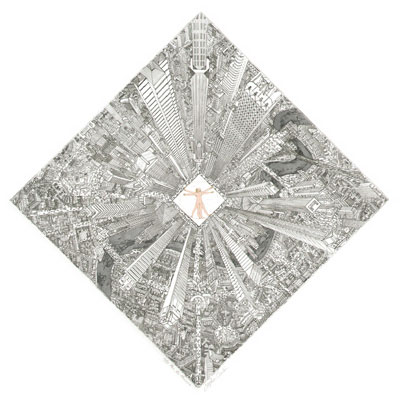

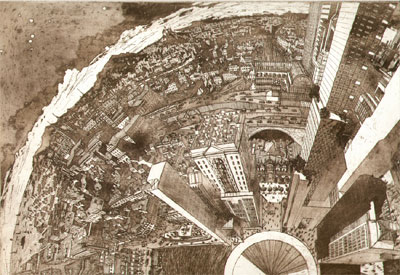

SC: I first saw Hollar’s work at about the age of six: it was one of his views of the City of London from Southwark and it fascinated me. You’re right, the attempt at exactitude was always there, even as a child I would spend hours over drawing, for example, an Ancient Greek city with columned buildings and people standing about.

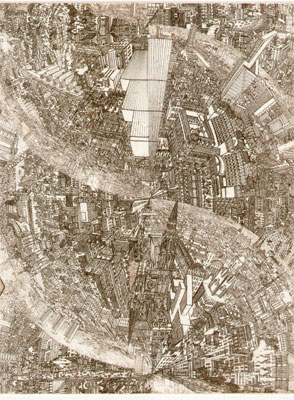

I have always loved images and panoramas of great cities, whether real or imagined.

Not having done an art foundation course, I have sometimes come to techniques late or even by chance. I didn’t add watercolour to the ink drawings until a relatively late stage, in my early twenties, because I was happy with the technical pen and what could be done with that. Instead of tone, for shadow I would use closely drawn lines, rather than cross-hatching.

I soon discovered that I enjoyed watercolour, and that was when I really had to confront light and shadow. I did some fantasy work in the 1980s so I needed to work out where light should fall. For etching and aquatint this had to be ‘stopped out’ using varnish, and then bitten by the acid.

Prague is a city that I have been visiting for almost 25 years, so it is part of my life and the way that I look at the built environment. Apart from the obvious beauty of the place, I feel that the city is the essence of Europe. In many ways, time spent there is a way of recapturing what was destroyed in the Second World War, when so many British and German cities lost their historic fabric.

Dresden is of course the most startling example, the destruction having come so late in the war, at a stage when many thought that the city would survive. To take the train from Prague to Dresden is to see two sides of the coin. I visited Dresden in the East German period and saw how little was done to recreate the historic core. Some of the fabric of the old town within a limited area has now been rebuilt. It is something of a freshly executed baroque stage-set, but it helps to recreate the ancient street pattern and is a good home for the great collections and the music life.

Goering threatened the Czechoslovak president in 1939 with the destruction of Prague in 40 minutes if he didn’t sign up to the submission of the Czech Lands to the German Reich. The irony of this is that no major German city today can supply the authentic atmosphere of Central Europe that Prague possesses. The Czech capital is a miraculous survival in so many ways and from so many dangers.

Slavka Sverakova is a writer on art.