SS: To start with: it may be not easy to capture in words the values that grew from your work being performed outside its context of origin. Nevertheless, this is a conversation about complex artworks that have a power to create their own context wherever they are. I have not listened to all From the rucksack, but so far I have perceived the meaning of the sounds being not rooted in language or in a national culture. How were the live sound performances of that work in Japan, in Kobe, installed? In what spaces? I think of space as a significant part of your work, ever since your early performances. We shall return to those later. You seem to be a multitasking artist with a flair for generous co-operation, a range of skills and a complete devotion. What are the essential skills for your kind of art practice?

DMcC: It was wonderful for me to be invited to Japan, as I feel that Japanese culture has always been an influence on my work, particularly Zen, and I had to reluctantly turn down an invitation to perform there in 2005 due to existing commitments with Cork 2005 . Yes, you are right, the sounds I tend to use have a universality and the work should work in any culture. Space influences my work hugely and I really enjoy working with space as a medium. I tend to let the space form the work rather that trying to impose the work in the space. When I am traveling, I tend to travel very light and let the work happen from what I find or can purchase cheaply on site. For the Kobe installation I brought with me a series of drawings I had been doing for the past year and some photographs that I had found in my aunt and uncle’s house that I had recently cleared out, and these formed the basis of the work along with some spools of coloured threads that I got there. The sound I used was also taken from the same house which had also been my grandfather’s and great grandfather’s, so I recorded the furniture, objects and surfaces in the house and from these recordings built up the work. Amazingly, the sound seemed to develop as a liquid form; it only occurred to me later that the house is part of a flood area and was regularly flooded.

As regards the live pieces, again the space influences the works and as I also use field recordings the whole general sound of the area influenced it. In particular, in the second piece I did in the Prefecture Museum Of Art I performed in a room with a piece of work, by Yukinori Yamamura, which included sculpture by Rodin and other very famous artists The main piece consisted of a huge hand which held the other sculptures. This was particularly interesting as it was a tactile piece and people were asked to wear blindfolds and masks when entering the room. So I got to perform to a mostly blindfolded audience (a bit like what Francisco López does all the time). I was also able to move around the space and take the sound with me and bounce it off the walls, etc…

The last part of your question has caused me to think very deep and the most truthful answer I can give is “;love,"; if love can be considered a skill. But I am passionately in love with art; my life is art every waking moment. As regards sound art, the most important aspect of that is without doubt my ‘listening practice’ and the ability to listen. I have given numerous listening workshops to people from literally eight to eighty and I am always fascinated by people’s reactions when they start to listen deeply. I have taught primary school kids and am currently teaching a course in the UCC Music Department called ‘Sounds like listening’; also, the practice is universal so there are no language barriers with listening.

SS: The ‘listening practice’ in your view has two directions: from the real to your art, from your art to your audience. There is, of course, a direct one between the real and the audience, one that your art aims to cultivate. Umberto Eco ( On beauty, 2004) makes a distinction between the beauty of provocation (as in Modernism) and the beauty of consumption (as in pop music, magazine, and other mass media). He conceives of both as contradicting each other. In your art the gap is narrower; in addition, it invites a rephrasing of Eco: beauty as provocation and as consumption. The seemingly unstoppable polytheism of beauty depends on the power of sensibility, irritability and reproduction. The first two come from your ability to accept some aspects of the space in which you work and to transform them. The third is meant as changes inside your art practice. You connect the unconnected – which is the power of mind called by some of us “eye music." It was coined in 1818 by J.E. Purkyne and again in 1848 by B. Bolzano. These ideas are embodied in many of your artworks. The commission of Wa(l)king the dream (2006) seems to me an extraordinary and poetic combination of a place, Cobh, and ‘the listening’. How did this happen, and how was it made?

DMcC: It is very interesting that you should ask about this work as it is a work in two parts – one an installation called Sounding the town and a sound performance called Wa(l)king the dream also that it was a collaborative piece with the UK / USA artist Viv Corringham. It came about as a result of a residency we had in the Sirius Arts Centre, Cobh, organised by Peggy Sue Adimson, the director there. The pieces seemed to grow out of the work we did in the town itself. We conducted listening and improvisation workshops there in schools, youth projects, residential and day-care centres and recorded all of these as potential sound sources. We also asked the question at these workshops and of people on the streets, “;If you had a magic wand what would you do for Cobh?"; We recorded the answers, which were amazing in their honesty, ranging from simple things like “;I would open a shoe shop"; to “;I would bring back the liners and Irish Steel."; It gave us an insight into the basic things that affected people’s lives. There were also some fantastic surreal replies. As well as these, I made a series of field recordings of the sounds of the town at various times of the day and night. As Viv was based in the USA and me in Ireland, we divided up the recordings with Viv talking mostly the voice-based ones, whilst I took mostly the sounds-based ones.

We had decided at a very early stage that we would like to include a live / performance-based element in the work and that the scale of that would depend on the budget available. When we got the budget, we were pleased to be able to achieve what we wanted, as it was important to us to be able to pay the other performers in the work. For the performance we made seven different recordings for seven ghetto blasters and gave one to each performer to carry in a brown paper bag with the word ‘LISTEN’ printed on the bags; they also wore white t-shirts with the word ‘LISTEN’ on them. They were then choreographed to walk through the streets of the town, passing each other at certain points, stopping, letting the sounds from each bag mix with each other, then all coming together on the town bandstand every half hour and then dispersing again to repeat the performance, which was never the same, as the sound of the town were constantly changing and mixing with the recordings.

For the installation, we discussed a lot of different possibilities, but during the course of a conversation someone said “;If these walls could talk,"; and that gave me the idea of a talking wall. For many years I have been collecting speakers of various shapes and sizes, so we decided to use some of them on the wall and have them exposed rather than hidden, as some of them were very visually interesting. So, with Viv working on voice-based work in the USA, I created two sound-based CDs here, one with five tracks and one with seventeen. The idea then was to play the three CDs on continuous random (shuffle) function, so the sound would be indeterminate and never be the same at any one time, which is a way I tend to make most of my installations. Once we set up the installation, we then remixed any tracks that needed it acoustically and omitted some that did not work in the space. We then wound up with sound coming from all sides of the wall, also moving from side to side, and speaker to speaker, and the wall itself also acting as a resonator.

So it was a totally new listening experience every time one visited and even we, the artists, couldn’t tell what was coming next, which made it interesting especially when a participant visited and we couldn’t tell them when they (ie, their sound) would appear. It was a very exciting and challenging project to work on; Viv is an amazing artist to work with and fulfilled my belief that “;every situation has creative potential."; By trusting and respecting each other as artists, we were able to create this work despite being so far apart physically for a lot of the time. We are hoping to release a CD of the project, as we have a lot of very interesting binaural recordings which were unused; but that really is another project.

SS: You have raised several significant points: One connects to live performance as a genre of visual arts, and the other relates to contemporary, on the edge, art practices that develop the sonic as an autonomous branch of visual culture. I take the sonic first in relation to the talking wall. The images of the speakers on the wall have their own aesthetic power; their rhythm grows into a confident composition with convincing pathways of visual force. Even the minimalist contrast of the ground and objects works well as a relief or a wall installation. I think that it would be successful even without the sound. However, that is not an option here, even if the visual is not waiting to be enhanced by the sonic, nor is it simply subordinated to it. This visual operates according to different rules from those that the sonic does: its position, appearance, sequencing are all fixed, all is predictable within the frame of the wall. The sonic works with opposite qualities: random, whimsical, unpredictable, surprising – all successful strategies to make people more attentive, willing to immerse into an act of listening. I am reminded of Nietzsche’s terminology from the Birth of tragedy : ‘Apollonian’ (the visual in this case) and ‘Dionysian’ (the sonic in this case). And that in turn reminds me of the link to theatre, which I sensed in your earlier performances. You are a visual artist and a musician, like, say Martin Creed and Janet Cardiff. Is theatre there somewhere too? How do you see your earlier performances now? Have you used noise in some of them?

DMcC: You have used a very interesting term here when you say ‘live performance’ and, as much as I hate labels, I feel the term ‘performance’ has been abused so much in recent years that I always now feel the need to clarify what I do as ‘performance art’ or ‘live art’. I think the term ‘performance’ has been misappropriated mainly by failed theatre directors to try to justify what they are doing and also by the ‘baby Abramovic boom’, where there are so many people running around ripping off Marina Abramovic, who herself is a superb artist, but she has spawned a lot of clones who, whatever they are doing, are not making ‘performance art’. They are doing something that is much more theatre-based that visual-art based. A certain amount of this is also due to the art colleges, who are failing in their education of performance art and sonic art also. It’s almost like there is no quality control in these areas, whilst at the same time they would not dream of showing the same disregard for painting or drawing, but on the other hand there are still some wonderful younger live artists coming through despite everything. Recently, I saw a very well know seminal piece of sound art being ripped off by a graduate who wasn’t even aware that they were ripping something off, which was good for them but asks questions about the education they got. It is great for me, as someone who has presented and promoted performance for over thirty years, to see resurgence in live-art activity. I have easily promoted and presented more performance art than anyone else in Ireland over twenty-five years’ involvement in Triskel and other organisations. I firmly believe that it’s the quality of the work that matters in the end.

As regards the ‘sonic wall’, I am always aware that when I include a visual element in a sound piece that it must be aesthetically right or else I will not use it. I think a lot of sound art falls down in the visual area but has got much better in recent times. For a piece to truly work, the sonic and the visual have to be as one. Also at present I am working on a new series entitled The Rematerialisation of sound as an art object, the title taken from Lucy Lippard’s famous book. The series deals with sound as a material, silence and listening.

As regards my earlier performances, I still stand over them and am still very pleased at some of the visual imagery and would love to make a show of some of the blown up photographs, if ever the opportunity arose. There have been difficult times for making performance art, with often very few opportunities to make work; for example, I did the first ever performance piece in ev+a, called You don’t have to be an artist to draw conclusions, by sneaking in the back door. They organised a show of previous prize winners and I was one of them, having won the sculpture section (selected by Pierre Restany) with my installation H based on the H-Blocks hunger strikes happening at the time. Always, in Cork (Triskel Arts Centre) we have operated an open-door policy and gave opportunities to artists to make work when no one else in the country was doing it. As regards myself, I have a strong sense of ritual which I incorporate into the work; this can be mistaken for theatre, but the work has never been based in theatre. It’s interesting now recalling some of the earlier work: one piece in particular – called Healing memories, where I stood motionless on waste ground at the side of a busy street for over eight hours – dealt with the ‘flooded areas’ of Mallow town; and my recent work in Japan was based on the same area, almost twenty years later.

As regards ‘noise’, it is a hugely important element in my work and I use it all the time, processing it, bending it, etc, using field recordings in live sound performance, etc. Many people think that to be a noise artist you have to be loud, but that is far from being the case. You can use noise really quietly also, the whole aesthetics of noise I find quiet fascinating. I am looking forward to reading my friend Paul Hegarty’s new book on the subject Noise / music a history, just published ( www.continuumbooks.com ).

SS: You have produced a number of CDs. How did this come about? I have noticed that you cherish co-operation with other artists, some from Cork, and others from Japan, Germany, etc. I have also noticed that the CDs coincide with anniversaries, eg Bend it like Beckett (2005), or with the annual festivals, eg Art Trail . How do you get other artists to take part?

DMcC: I have produced several CDs, both solo and compilations. Many of the solo ones are of installations or live works and would be in limited editions. As regards the compilations, the first one I did was a cassette which I had forgotten about until recently when I was talking to Megs Morley of the Irish Artists Archive: it was called Telephone artline and consisted of tracks produced especially to be heard over the telephone as part of a project I initiated again called Telephone artline, where each work could be heard for a week by dialling a number and the work was played back via an answering machine. It was produced in Triskel Arts Centre. This was in pre- digital days but was followed by another version, which I organised for SSI (Sculptors’ Society Of Ireland) with the support of the eircom; I used their new incoming digital technology for the first time ever. Other compilations would include one to mark ten years of Intermedia, an annual festival that ran all through the 90s which I organised in Triskel. We decided to mark ten years of it by producing a CD of some of the artists that had appeared at it over the years and included leading international names like David Toop, Scanner, Bachet Bros., alongside some leading Irish exponents. I happen to be friends with David Toop and once you have David on board it’s very easy to get others. Another one I did was for the book that Julie Forrester and I co-edited called For those who have ears, the first book on sound art produced in Ireland. It was easy, as most of the tracks related to articles in the book. I did a CD for Sound out, the major exhibition of outdoor sound art co-curated with David Toop for Cork 2005 European Capital of Culture . That consisted of the work by Christiana Kubisch, Max Eastley, Scanner and Akio Suzuki, four of the leading practitioners in the world. The most recent one I did was for Art Trail and was called Bend it like Beckett . This was produced to mark the centenary of Beckett’s birth and consisted of one hundred pieces with each track to be no more than one minute long. It consisted of invited artists and open submission also. I had much more material than I could include, but eventually wound up with about eighty artists from around twenty countries. That, I must say, was really hard work but was worth it in the end. I have also myself appeared on numerous compilations in various places around the world.

SS: You have visited Le Lieu in Quebec in October. They do not have a strong tradition of sound art. What did you perform there?

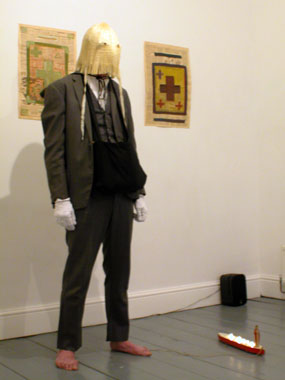

DMcC: Le Lieu is very well known as a centre of live art but has always been interested and supportive of sound art and they have done several festivals and produced cassettes and LPs in the area; they are currently producing a special edition of their magazine Inter on sound art. I was invited there many years ago and could not go so I did a tape-slide piece instead with a live telephone link up from my studio in Cork, which seemed to work very well as the piece was about emigration and communication. Where once it took a letter months to arrive from there now all one has to do is press a button. This time I did an installation called (Re)sounding memories / watering the plants, which is a continuation of the work done previously in Berlin and Japan dealing with memory and impermanency. I also did a live sound performance called Listen out loud using my normal set up but using field recording I would have made in Quebec and on my way there.

SS: I have received the e-mail about the DEAF closing party in Dublin. What is that about? What kind of sound work did the participants produce? For example, the Japanese soul and house appear to me like straightforward jazz and not sonic art as a genre. By this I mean the defining performances like those by Frequencies in Frankfurt in 2002, and not the Raw Material performed by Bruce Nauman for the Tate Modern last year.

DMcC: Yes, DEAF (Dublin Electronic Arts Festival) caters for very many different forms of electronic music from Dance to House, etc. but is also opening up other forms and hopefully will continue to grow and expand. It operates on a shoestring budget and should get more support. They seem to be opening up to the area of sound art and hopefully will include installations, etc in the future. This year we, The Quiet Club (Mick O’Shea and I with guest Harry Moore), played in a karaoke club with about seven or eight Japanese and Chinese artists. Each of us occupied a karaoke booth, the sound from one mixing with sound from the other whilst the audience was encouraged to move around the building from booth to booth. We played non stop for about two hours. It was a really interesting experience, a bit like the Sonic vigil, which we organised in St Finbarr’s Cathedral in Cork, where about twenty artists were spread around the cathedral and we played for twelve hours from noon to midnight.

Slavka Sverakova is a writer on visual art.