SS: The paintings I saw at the Mullan Gallery in 2007 were different from your previous dark images drawn over multicoloured maps. You have mentioned a residency that inspired that departure. What contributed to that change?

CW: There were two residencies that proved important for enabling the development of the work that formed the basis for the Mullan Gallery show in 2007.

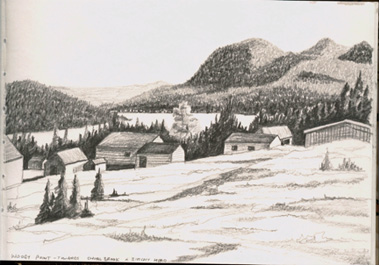

The first was a residency at Gros Morne National Park in 2002. I had previously been to Newfoundland and was determined to return for a longer period and work there. The Gros Morne programme was run jointly by Parks Canada and the Art Gallery of Newfoundland and Labrador at Memorial University. For me the unique geological landscape of this area combined with the elements of human habitation were of great interest, I was focusing my responses towards the landscape in terms of scale, distance and the vulnerable presence of small dwellings and harbours.

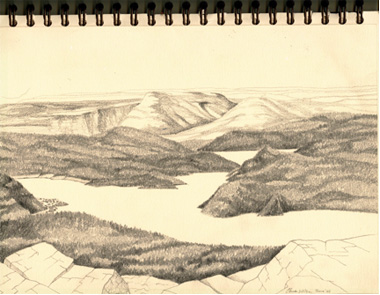

The landscape has many unique features including no less than the physical evidence for two geological time periods, also a part of the ocean floor pushed up onto the surface to form the Tablelands.

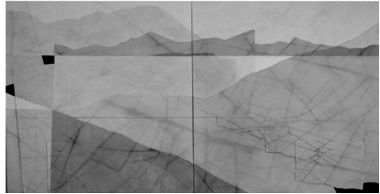

For six weeks I walked and recorded vistas and panoramas and only towards the end of my time did I reflect on the fact that most of my vision had been directed towards horizons whereas it was really the ground and rocks over which I walked that held the key.

For several years my ‘map works’ had played with relationships between shifting viewpoints and multiple perspectives.

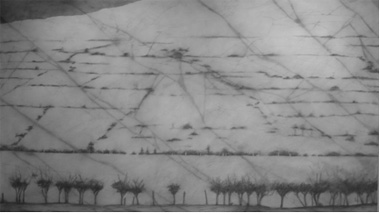

Cubism was a very early interest. Once I started to re-examine these ideas in combination with my Gros Morne experience, I began to visualise pathways that were at the core of how to deal with landscape in the many ways in which we now experience it, ie from the normal linear perspective and also from an aerial perspective.

The Newfoundland experience had opened up a number of thought patterns that I wanted to explore but the materials that I had been using up till then did not allow me to realise the ideas immediately.

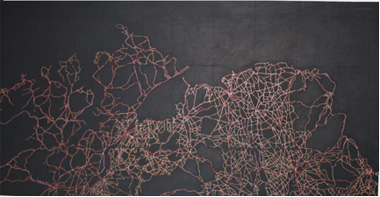

Works like Coastlines evolved at this time, where I was drawing with conté over the real Ordnance Survey maps so much that I blacked out the information between the roads and left only connections between places. I made a series of these pictures that were almost completely black but for a fine filigree of networks. But I still had not got to the core of what I was after.

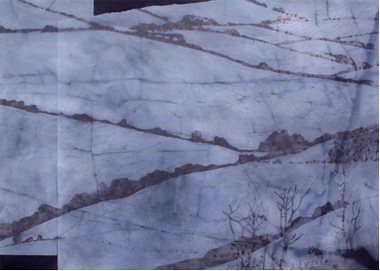

It was during the second residency at the Robert M MacNamara Foundation in Maine in 2003 that I finally developed new methodologies through using gesso and acrylic with graphite to create layers of marks and painted surfaces which allowed me to expose and hide different layers, thereby creating a history of mark-making, some quite strong, others barely visible. Once I related these methods to multiple viewpoints and shifting perspectives, my landscape painting developed into a kind of synthesis of my previous concepts and the new look.

SS: It illustrates the role of new experience nourishing an older paradigm, changing it a bit. However, there is a consistency in your work despite some apparent twists. I recall your MFA exhibition of a group of small metal houses, the grey tonality and volume would appear later in the newest paintings. What led you to subdue your interest in sculpture? During 1988 you made collages and sculpture, for example, for the Clear Focus exhibition at the Narrow Water Gallery. Sean McCrum observed then that your work was inspired by abandoned interiors and by sequences obtained by photography.

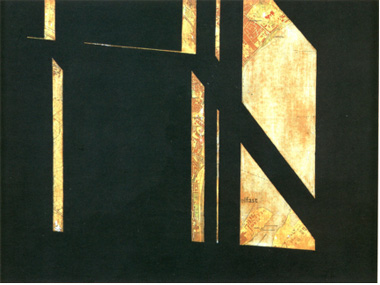

CW: There was never a conscious decision to subdue my involvement with sculpture. Those sculptures had employed the symbolism of closed forms, no doors or windows, a stage that introduced to me a question how to get inside. Around 1986 – 87 I began to explore it by transforming the Ordnance Survey map of Belfast.

Both the sheet-steel sculptures and the map works involved transformation of flat material: in case of the sculpture the flat plate formed the three-dimensional house, in the case of the map the pictorial space offered an illusion of three dimensions.

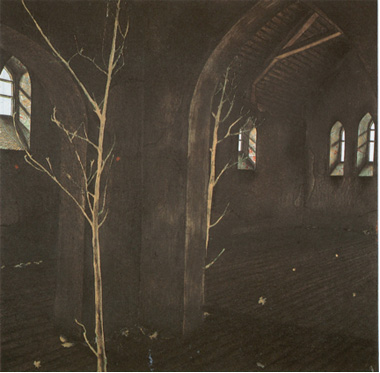

The map constructions allowed me inside the enclosed spaces. At a particular junction this material provided access to explore the psychology of enclosure and isolation, which was connected to the wider political and social environment of the city at that time. All of my production has been an exploration of materials and the specific history trails of particular materials: steel is industrial and carries a history; the maps referred to borders and boundaries; while the interiors of houses or churches created connections to private individual thoughts and feelings.

I never added any colour to either method of working but rather allowed the material to be the primary driver, akin to minimalism; even with the maps the colours were part of the printed surface, my additions and transformations only involved using black conté which I could rub into the surface with my fingers. I very much considered the ‘map works’ as constructed spaces.

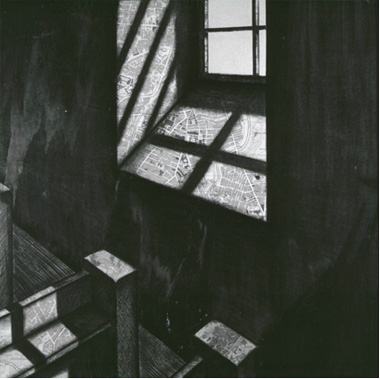

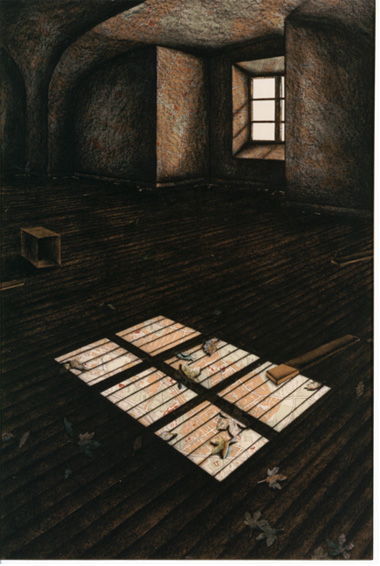

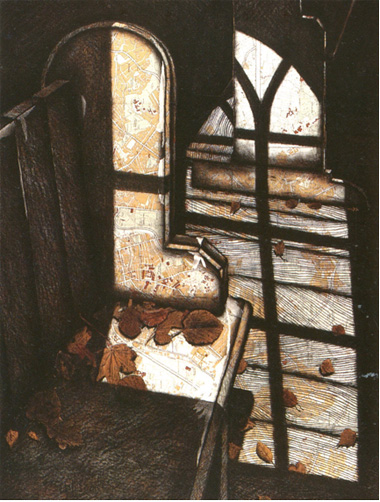

With the early ‘map works’ I often used abandoned industrial spaces or church interiors when unoccupied; also I would gain access to an empty house on the market. At that time in the 1980s, some estate agents would just lend a key and allow you to view the property by yourself.

I would spend time drawing the interior, how the light would enter a window and fall across the floor; this gathering of detail often found its way into compositions that took place in the studio.

SS: You have described a fluent development of your art practice from actual three dimensions to a pictorial one, from steel to maps, to gesso, from history to private thoughts. During the 1990s you worked as a visiting lecturer in the USA and England. You also became the director of the Glebe Gallery. How, if at all, have these experiences facilitated, or not, your own art work and exhibitions?

CW: My time at the Glebe Gallery was punctuated with periods of intense work organising exhibitions in the summer months, but the winter was a time when I could develop my own practice; that and the lecturing gave me some financial security, which was important at that time, it allowed me to develop new ideas and strategies. Up until the move to the Glebe I was becoming restless; I needed a change and a new landscape outside of the city. This turned out in retrospect to contribute enormously to a simplification of the interior compositions, almost an abstraction where light falling through single window frames and illuminating recesses would be used to focus the viewer more on the actual map material rather than so much on the structure. I now think that these developments were a response to the surrounding landscape where the intense blacks of the night would be punctuated with the light from an open door or window. Eventually this strategy developed to a point where I was making almost completely black compositions.

SS: After you moved to North Antrim, comments on your paintings, for these are now paintings, linked you to ‘northern romanticism’, to ‘multiple interconnectivity’ and to the mood known from high-contrast photographs. Do you recognise any of this, on reflection, as salient points? I have in mind exhibitions in Dublin and Belfast.

CW: When I moved to the north Antrim coast it was some time before the landscape became fully integrated into the work. I had started to record aspects of the cliffs and coastline with a view to developing ideas related to the boundary between land and sea. These were not necessarily new ideas; I still incorporated shifting perspectives and multiple viewpoints. These compositions, which I continue to develop, refer to changing landscapes, the layers and different perspectives, to push and pull, making it difficult for a viewer to establish a fixed viewpoint. The form is still rooted in the ‘map works’; however, I pursue now more complicated compositions, which reflect concerns about landscape and people’s impact on it.

I suppose in many ways any interest in landscape is romantic and certainly early influences included Friedrich’s Monk by the sea .

SS:I perceive your oeuvre so far as a story of light and dark. Both in the optical and psychological sense. The grey paintings tell me of some sort of peaceful agreement between the two. I remember an image with pale blue windows high up promising that kind of change. The light intrigues me also in those images where you use black – is it ink? – to draw the trunks of the trees over a multicoloured map. How do you achieve the gradation here? The shadows?

CW: For me it is interesting that you mention this sense of agreement, I have never been aware of any fracture in periods of work but rather that my focus shifts along new pathways revealed by previous developments.

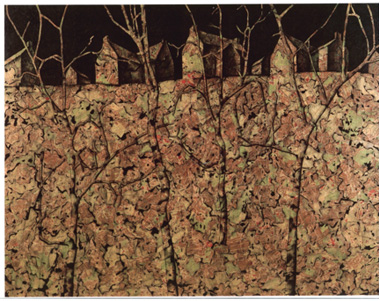

In the early map works, including the interiors and urban parks with the focus on trees, I used only conté, which I rubbed into the surface.

The tree pictures were created by cutting out from maps hundreds of individual leaves and building a uniform surface which was given shape and form by creating shadows around the leaves, almost like standing in a wood looking down onto the ground below one’s feet; this was really an aerial perspective which was often complicated by imposing a linear perspective, shadows from trees, the form of surrounding houses, etc.

All of these surfaces were created by using the black conté and rubbing, tearing and sanding the surfaces to create textures and depth.

SS: I see your point about the continuity, when you say that the tree pictures evoked “standing in a wood looking down” and the Gros Morne drawings were of “ground and rocks over which I walked.” Also the layering, be it of cut-outs or of paint, supports that. Nevertheless, there are differences between the steel houses, the ‘map works’ and the gesso paintings that, for me, parallel the myth of coming out of the darkness of sorts. The recent paintings, in their subtle variants of greys, present an agreement between light and dark, between being in isolation and out in the natural world. I note a celebratory tones there too.

Slavka Sverakova is a writer on art.