SS: Your latest exhibition in Hugh Mulholland’s The Third Space (Belfast 2007), metaphorically speaking, joined forces to fill your CV together with an earlier awards of the PhD, with a lectureship at the University of Ulster, and with the birth of your second daughter. A high degree of multitasking calls for more than dedication and clear planning, the ‘more’ in this case is the computer assisted work. How has the technology assisted, inspired, made possible to embody your intentions in the exhibition you called Dark Matter?

AOB: I am still digesting the work made for Dark Matter, so your question is generous and helpful in allowing me to process it. This body of work started as an inquiry into the nature of space according to contemporary physics, but as my research unfolded I began to realise that it was as much, if not perhaps more, an investigation into time. This maybe makes sense in relation to your comments about multitasking and time management, not normally my forte; however, technology was of help in terms of timing, in making the animation and as a medium to show it.

I wanted to make a show that involved drawing as a major element for some time, where the drawing contained a type of narrative about the relationship between technology and theories about space, so animation seemed the solution. The way I used the technology (Flash, an animation package) was very low-fi (considering what can be done in Flash). This approach was out of necessity but hopefully served to reflect the ironic simplicity of some of the ideas about space that I was examining. Essentially, it was just a stop-frame animation, but because I was working on a computer with each ‘story’, I was continually, slightly changing an existing image rather than having to re-draw it each time. It was worked on incrementally, so I could juggle it with other things I was doing. In this the technology served as both a pragmatic tool to make the work and as a medium to articulate it.

SS: We could think together about the time-space continuum; that idea is firmly inside your current art work. However, I have more pressing questions, before we gaze into the future.

The first one connects your present work with a very early one. I remember your gift of a wonderful drawing from Bratislava, sent to me in a letter. It is related to two themes: one is your constant faithfulness to drawing as a medium, the other is the story of your sojourn in Bratislava. Which of the two themes you wish to address first?

AOB: I’ll try to answer these points together. Retrospect is a great thing. You mentioning drawing and Bratislava in the same breath makes me think of drawing as a site-specific activity. My time on a Pepinière residency in Bratislava over the winter of 1996 / 97 made me realise that site, as much as medium, can be a valid vehicle for work, most especially when the site poses problems. Whilst in Bratislava (capital of the newly independent but economically pressured Slovakia), I encountered many logistical problems linked to personal circumstances, the political climate in the city at the time, and pressures faced by the residency hosts.

The story now seems long and boring (save to say I was broke and isolated and very nearly packed it all in), so I’ll just stick to the salient points relating to drawing as a site-specific activity.

The residency was normally to culminate in an exhibition for all the artists (there were two other resident artists), but it was cancelled by the hosts due to a series of misunderstandings and lack of communication between the artists and the hosts. The cancellation led to understandable bad feeling on all sides. Given the lack of communication, I wanted to do something as a form of protest without being completely negative about the residency experience. I decided to do a fake invite, drawing attention to the cancelled event. I made 60 cards detailing the cancellation.

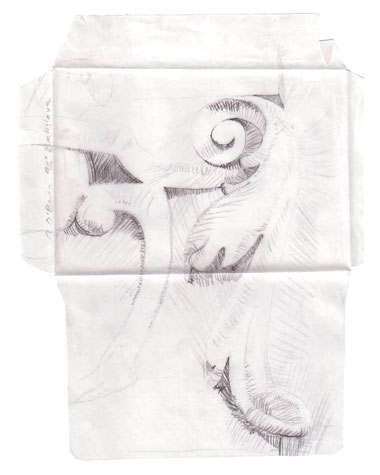

The envelopes for the cards were drawings of Baroque architectural details from around Bratislava. These were mailed out to my mailing list of galleries, organisations and interested individuals at the time a mailout would have been sent had the exhibition happened. These are the drawings you refer to.

Whilst at the time I would have said that the residency was a very negative experience, I now recognise the extent to which it informed my practice in a positive manner. At the time, I would have classed my invites as a one off action but now I see it as making a relationship between drawing and place. I guess it was a site-specific project. Since ’97 I have made a lot of site-specific work. Each time I approach a new site I think of my time in Bratislava and I am very glad I stuck it out, much as I am glad that drawing has remained an integral part of my practice.

SS: At that time you sent out an invitation to a dialogue, replacing the cancelled exhibition of your art and that of Marc Le Bris from France… “in an effort to combat censorship and lack of professionalism we encountered.” The sad thing is, that at present the Slovak government keeps censoring both television and newspapers. While in 1996 it could have been seen as a residuum of the totalitarian regime, the new wave of state control now points to something comfortably embedded in that society.

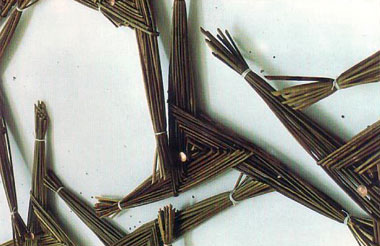

Your drawings on transparent tracing paper visually praise transparency so absent in a number of political acts anywhere. The drawings are, for me, a sign of authenticity, of your awareness of ethical / political dimension. They, and the text of the invitation tell a story, not unlike the stories you started collecting for Hidden Histories, exhibited at the Crescent Art Centre in 1992. These were drawings and sculptures. It intrigues me that over some two years, 1993, 1994, you made sculptures from reeds which looked like drawings, from suspended milk bottles with photographs inside, which looked like an installation, and from cast concrete, which looked like sculpture. In Bremen you showed prints of natural forms, I believe. Some ten exhibitions are witness to the vast range and quantity of your work committed to expose overlooked connections. Would you, please, cast your mind back to some of them?

A.O’B Wow! This is a blast from the past. It seems so long since I made these works that I’ve almost forgotten them, especially as I lost every shred of documentation for some of these projects in the Flaxart fire (Flaxart studios went on fire in 2003, we lost everything in the fire).

Some I can hark back on by looking at dated analogue documentation, for others I have to rely on my memory.

Hugh Mulholland (The Third Space Gallery and founder of The Context Gallery) has helped me out with some slides from the show Many Departures Available (Context Gallery 1994), whilst the sculptures made from prints in the Bremen show are consigned to an inaccurate memory bank.

With hindsight, I can see how all of these works could be seen as an enquiry into what drawing and installation might be. This was the first five years after I left college, so it makes sense that I was trying things out in an attempt to explore the metaphorical possibilities of different sets of materials in particular spaces. Some of these projects were less successful than others (to say the least), but I can now see that my approach to sculpture comes from a joint strategy of drawing in space and enlisting anything and everything as a ‘drawing‘ material. Sometimes the result was all-singing and all-dancing, on other occasions ideas were not pushed far enough, but all the activity was necessary at the time. Oddly enough, losing all that documentation and old work might have been a blessing – not that people might see patchy work years later, but that without it I was able to move onto fresh pastures, taking salient lessons with me without the burden of too much baggage.

I had been thinking for many years that I had let drawing slip from my practice until the animations of recent years, but it now seems apparent that drawing is a strategy that drives much of my practice.

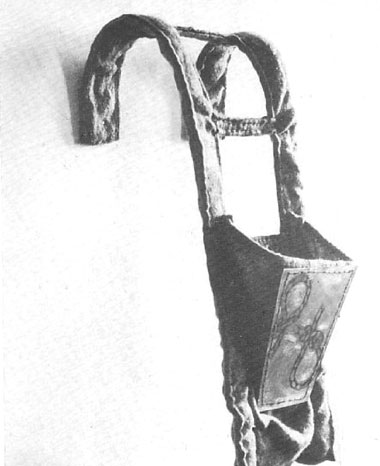

SS: In the late 1980s and during the 1990s your art sometimes appeared in more than three exhibitions per year. Some were one-person shows, like Hidden Histories (Crescent Arts Centre, Belfast, October, 1992). I think of that exhibition as the foundation for your further development. Both in terms of the range of materials you use (concrete, lead, wire, rope, aluminium, blanket, sack, steel, copper and drawings), and in terms of a strong bind between the tacit and the verbal. The tacit object, say the Lead Shoes, is a remarkable case of a floor sculpture and a stimulus to recall what is known and preserved in common narrative. I recall that there was not enough support for that kind of art in Northern Ireland; how did you manage to persuade galleries to take it on?

AOB: In the early 1990s I was trying to find my feet both in terms of the ethos of my work and the practicalities of getting it shown. Looking back, I explored a number of tacks.

The experimentation with a variety of materials was part of this process and is still an important element of my work now. I still try to use a range and exploit the physical qualities of various materials in my work.

The first few years after college were difficult and isolating, as it was hard to find a focus without deadlines or specific things to work towards, a common problem faced by many graduates. After a few years of seemingly aimless flailing around, I made a concerted effort to try to get involved in artist run activities and get the work shown.

The early ’90s in Belfast saw a time when there was very little infrastructure to support recent graduates and artists just starting out. As a result, many artists who decided to stay in Belfast (breaking the almost automatic trend to leave) became involved in setting up artist-run initiatives out of necessity. Ironically the lack of infrastructure led to a healthy proactive culture amongst artists in Belfast. I got involved in Flaxart, the artist run studios where I still work. This gave me the camaraderie of working with other artists and involvement in the development of the studio’s activities, such as the international residency programme.

This involvement gave me experience in an organisation, contacts and debate with artists abroad, providing a productive context to develop my own practice. I also got involved in a number of artist-organised exchanges and exhibitions in the early and mid 1990s. All of this I believe helped me to make and get work shown.

I was lucky to get the early shows that you mention as they gave me deadlines to work to and made me try to consolidate my practice. The show Hidden Histories in the Crescent Arts Centre came about when Chris Bailey was the director. When I was at college, we had a group student show in Harmony Hill Arts Centre in Lisburn where he was then director, so he was supportive of my practice when I approached the Crescent about having a show there. Hugh Mulholland, director of The Third Space, which now represents me, has long supported my practice. Hugh was a year above me in college, so has known my work for a long time. He gave my first show in Derry in the first Context Gallery (which he founded) in the early 1990s.

SS: I recall my uncertainty about Temporary Provisions (Ormeau Baths Gallery, Belfast, 2002). Many pots of plants, some video cameras, lot of taped wires – all above my head in the upper gallery. The plants and cameras, holding fast to their autonomous characters, were placed as if on corners of a street map, something I did not see before you told me. The whole appeared chaotic to me. In relation to your interest in urban stories, this installation felt supremely visual, dealing with space, depending on space, and evoking yet another space. For this, I perceive it now as another seminal work; I find all the following having roots in it: Urban Projects (2002), Urban Myths (2002 ), A Small Urban Inventory (2005) and your contribution to the Venice Biennial (2005). You’re collecting street names, nicknames, stories and sayings and thus borrow skills of the ethnographer or historian. Yet, neither can fathom your intention to turn the ordinary and idiosyncratic into political art. You say on yourweb site ( www.aislingobeirn.com ) that unofficial information reveals the politics of place. Had the Belfast sayings printed on coffee cups on Giudecca, or the green bags with grains for San Marco’s pigeons, utilised that concept to your satisfaction?

AOB: Yes, I agree that Temporary Provisions marked a turning point in my practice. In this piece I was trying to make a relationship between sets of information (by using suspended objects to map all the military installations in Belfast). I was also trying to highlight how they had become almost invisible even ordinary, which I guess links it to all the subsequent pieces that you mention as they all are generated from vernacular information about the ordinary, but the material is not always confined to Belfast. You could say that these pieces were part of a series all derived from an ongoing body of research into vernacular accounts of place.

Urban Projects (a series of sculptural works) and Urban Myths (a site-specific project using doormats and the radio and later a series of videos) both sought a way to retell vernacular anecdotes.

A Small Urban Inventory was an installation constructed from signs made from my collection of hand-drawn maps, accompanied by a website containing material from my ever-growing collection on anecdotes, nicknames and hand-drawn maps.

Although some (not all) of the research pertains to historical events, I don’t see the work as purely historical, as the bulk of it deals with contemporary information such as place nicknames, which are used now, or hand-drawn maps of existing places. Though the research started out with Belfast-based material ( Urban Projects ), it quickly snowballed into a collection from everywhere. The ethnographical strategy is word of mouth. As much of the material initially came from Belfast and as I live there, in the case of Belfast I am just not an external observer, I must also be a participant. The collection of anecdotes and nicknames started because I came across them through living in the city.

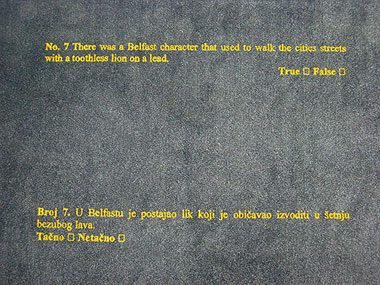

The work in Venice took the form of a public project where I found systems to distribute some vernacular anecdotes about Belfast. I was interested in trying to find vernacular activity in Venice, so the vehicles I used to distribute my stories had to be informal in a city that is often represented in a very formalised fashion (we can all conjure up an image of Venice without ever having been there).

So using pigeon-feed bags used by the thousands of tourists that feed St. Mark’s pigeons and cups used by Venetians drinking coffee seemed like low-key strategies that might work.

The Belfast stories used all had tentative links with Venice (ie, choosing Buck Alec’s Belfast lion whilst thinking of St Mark’s lion, the emblem of Venice).

It appealed to me that these stories might find their way into the city in a low-key way, given Venice’s reputation as a city familiar with spectacular statements.

I see all this work as being political (rather than me attempting to make it political) because of, not despite, the informal nature of the information. However, saying that, I should qualify what I mean by ‘political’. The anecdotes, nicknames, maps all serve to describe how people describe, occupy and utilise their environments. To me this is politics in action.

Both a shortcoming and a possible success of all these works is that they have led me on to gather more research and make new works.

Slavka Sverakova is a writer on art.