|

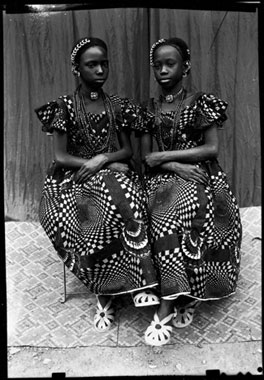

| Seydou Keïta: Untitled, 1950-1955, silver gelatin print, ©Association Seydou Keïta, Bamako, Mali, courtesy Association Seydou Keïta, Bamako / Sean Kelly Gallery, New York / JM Patras, Paris / Douglas Hyde Gallery, Dublin |

Bar Mali sits on a corner of the dusty Avenue Mamadou KonatÈ in Bamako, the capital of what is now known as Mali. On the map Mali resembles a geometric shape that has been dropped from a height. In the north the frontier cuts in straight lines through desert while in its crumpled south its border jostles with those of its populous neighbours and it is here that most of the population live.

Outside the bar the traffic police take a break from their whistles to watch football on the veranda, a ramshackle porch which straddles the open sewer. Inside, by the glow of a naked bulb and another television, a group of men are in loud drunken debate. They jump up and down in their seats like excited teenagers. Sitting directly opposite, lined up against the wall as in a doctor’s waiting room, are five women dressed in black. In Mali it is unusual for women to wear such a dark colour. They are almost motionless as they survey the room with disinterest.

One by one the women make their approach and ask to be bought a Guinness. One girl, diminutive and soft spoken, tells of her journey to Mali from the Cameroon, the only journey of her life so far. She speaks with detachment about Africa and only becomes animated when she starts to talk about Europe and the prospect of getting there someday. Her vision of Europe is as faithfully optimistic as the western one of Africa is bleak.

*

|

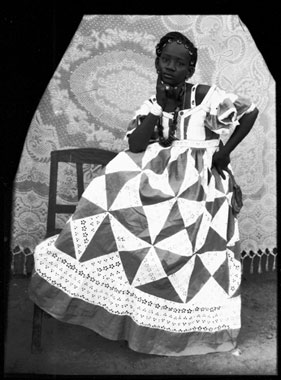

| Seydou Keïta: Untitled, 1950-1955, silver gelatin print, ©Association Seydou Keïta, Bamako, Mali, courtesy Association Seydou Keïta, Bamako / Sean Kelly Gallery, New York / JM Patras, Paris / Douglas Hyde Gallery, Dublin |

Seydou Keita started taking photographs of the people of Bamako in 1945. He began nervously by taking photos of his family and, gradually gaining in confidence, was photographing for clients in earnest by 1948. His studio became quite popular and Keita recalls queues of people on Saturdays, waiting to sit for their portrait. Looking at the ten modest works in this current show at the Douglas Hyde Gallery it is easy to imagine a world lost to the ravages of debt and mismanagement. Most of these shots were taken about ten years before the wave of independence which cut the ropes, at least in name, from the longstanding colonial rulers. Many of these studio shots seem almost Victorian in composition and the sitters appear dutifully uncomfortable with this. Keita has arranged the women’s garments against the patterned and embroidered backdrops with a keen eye for pattern and contrast which lends them an almost iconic gravity.

|

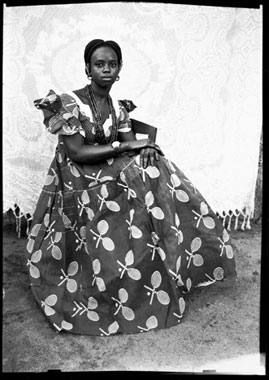

| Seydou Keïta: Untitled, 1950-1955, silver gelatin print, ©Association Seydou Keïta, Bamako, Mali, courtesy Association Seydou Keïta, Bamako / Sean Kelly Gallery, New York / JM Patras, Paris / Douglas Hyde Gallery, Dublin |

Keita’s studio was equipped with some props which included European suits, a fountain pen and plastic flowers. The same props appear in several of his portraits and some of the sitters seem uncomfortable and self-conscious with them. There is a portrait which does not appear in the current show, of a well built young man holding a small transistor radio by his side. He stands coyly, three-quarter towards the camera, shirt sleeves rolled to the elbow, hat perched on the back of his head like an annoyance, his free hand jammed awkwardly in the watch pocket of his zip-up cardigan. The mute masculinity of the sitter seems at odds with the contrived theatricality of the studio setting.

However, it is Keita’s photographs of women which predominate in this selection. There are frumpy women who stare glumly at the camera with bemused infants wriggling on their laps, almost lost in the confusion of billowing garments. The most striking, however, are the images of young women on their own. A young woman stands confidently, one leg resting on a chair, her hand on her hip. Her presence is at once one of stability and grace, which is echoed in the triangular pattern of her dress. Her entire body forms a solid triangle on the dusty ground. The young women in these shots seem to exude a sense of assurance which effortlessly bridges the gap of an African nation in transition. There is an ease and optimism for the future evident in these shots.

|

| Seydou Keïta: Untitled, 1950-1955, silver gelatin print, ©Association Seydou Keïta, Bamako, Mali, courtesy Association Seydou Keïta, Bamako / Sean Kelly Gallery, New York / JM Patras, Paris / Douglas Hyde Gallery, Dublin |

This ease can still be seen on the streets of Bamako where, during the Muslim festival of Tabaski, young women spend long hours getting their hair coiffeured into elaborate creations and walk the dusty neighbourhoods in vividly coloured dresses. The focus of optimism may have shifted, however, as everywhere there are people desperate to fill their pocket address books with the names of the travellers who pass through the region with envious ease. The relationship of an African nation such as Mali to Europe and the ‘west’ has always been complex and is no less so today than during the fluid early days of independence. In Keita’s portraits the sitters may be awkwardly appropriating the western convention of memorializing through formal photography, but in Bamako today, French and American rap music is as ubiquitous on the tape decks of taxis and bach é s * as traditional Malian music is at Parisian dinner parties. The African and European perspectives seem to depend on mutual illusion and miscomprehension. Bamako sees a surprising number of visitors resting up on their journeys in search of what they term ‘the real Africa’. They seem oblivious to the electric and often contradictory realities of the city they pass through. For many of those who never visit, the notion of a pre-independence Africa is one of complete oppression while the perception of Africa today is one of complete dependence. As with all perception, these notions are only aspects of the reality.

|

| Seydou Keïta: Untitled, 1950-1955, silver gelatin print, ©Association Seydou Keïta, Bamako, Mali, courtesy Association Seydou Keïta, Bamako / Sean Kelly Gallery, New York / JM Patras, Paris / Douglas Hyde Gallery, Dublin |

Keita captured the people of Bamako during a period of transition. What we see are people not entirely at ease within the polished framework of this very ‘western’ medium. Fifty years on it is not certain that the relation of African nations to Europe has developed any more significantly.

Robbie O’Halloran is an artist and writer on art who has travelled in West Africa.

*A bach é is a local term for a shared taxi, usually a small van.