Elizabeth Cope’s painting belongs partly to the Mediterranean and partly to Northern Europe, combining as it does the richly decorative and the harshly, brutally expressive: sensuousness and the skull; all tempered by humour and a type of domestic allusion that soothes and lulls the viewer into a security of vision. The landscape is initially familiar but all is not what it seems at first glance.

There must be something deeper speaking out; if you don’t dream you don’t do anything. [1]

At a recent exhibition, Nudes on display, at her London studio, Cope had juxtaposed sets of nudes to illuminate certain themes that permeate her work. In one set, a conventional nude is placed next to a less conventional, somewhat abstracted nude study. I would maintain that the first nude addresses the idea of the power of mind over the restraint of body. A tranquil figure is diagonally positioned in a way that does not undermine the sense of stillness in the painting. One soon realises why: the body is not animated by mind; the mind has separated itself in one of those conditions often associated with pre-pubescent girls or people in prayer or meditation. The background appears flat but closer inspection reveals the merest hint of depth at the top right hand of the picture – a doorway? Where the body might be subject to social and biological constraints, the mind is free to go anywhere.

When I’m painting a portrait I’m painting myself anyway.

In the second nude study the emphasis falls on the sexual objectification of the female – the obliteration of individuality by the dominating power of gender and procreative sex. Here we have not so much a separation of mind from body as an obliteration of everything unrelated to the sexual organs. There is a sense of the brutal and macabre in the way this female torso has been cut out of hardboard and attached to canvas. Limbless like one of those ancient statues and with only a suggestion of a head, this piece combines a cool blue-grey background with the warm oranges, pinks and greens of the flesh tones on the cut-out. The background colour naturally recedes and the flesh advances, even more so since it is in relief. This floating, suspended, depersonalised shape – the face not functioning as a reflection of ‘personality’, the limbs disempowered, not even present to act – draws the gaze towards the earth-rich wound of the sex organ which is the subject of the painting. One wonders if the sense of suspension echoes too the pre-orgasmic condition in which all restraint is abandoned and the body lies prone to its destiny. Viewed in another way, the configuration of breasts, nipples and abdomen create a face – a slight nod in the direction of Magritte’s The Rape?

Another pair of nudes illustrates the twin notions of being and doing. One figure is in profile – the slope of her back is rather touching in this tranquillity of vulnerable self-possession. It is reminiscent of the work of Matisse in the use of red and blue – the blue giving a suggestion of depth in this otherwise flattened study where the emphasis is on the sleeping figure and there is no social context. By contrast, the painting placed next to it is firmly located in a domestic milieu containing crockery, furniture, a mirror and a picture. The full-breasted nude is facing out with full gaze, the lower body painted in a way suggestive of an apron. The colours are citrus-fresh with turquoise contrast against the flesh pinks. It has the female confidence one remembers from those cheerful kitchens of fifties and sixties sitcoms, where all problems were ‘happy’.

Another nude, again in profile, is a slender sleeping figure, her arm rather languidly positioned; her shoulder blade vulnerable; her body contrasted with the plush red richness of the sofa back. This is not a public pose and the viewer feels a sense of tenderness for the surrender of the sleeper. The contrasting piece combines the decorative with the figurative. The floorboards painted in earthy tones create a domestic space for the figure and also have a decorative function. The figure faces forwards but the eyes are averted from the viewer in the privacy of thought.

I must be prepared to expose myself and not in a therapeutic way.

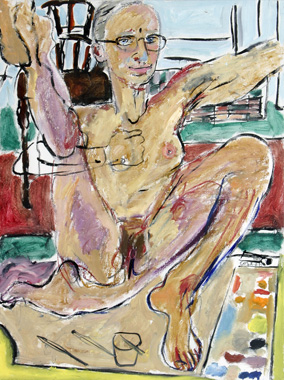

A nude portrait of the artist (is it coincidence that it is placed beneath a very bright light?) links with the mood of Cope’s large nudes recently presented in the Fís exhibition in Liverpool. There is a frenetic sense of body abandonment – the legs open to reveal the sex wound and a third leg held up though not in joy, I would suggest. Contrasted with this, the tools of the trade: brushes, knives, scalpels…are lined in rigorous order, in readiness for the day job. The paint has been energetically applied and the expression in the eyes is enigmatic. What is known and what is concealed from the viewer, from the subject herself? The suggestion is that the artist in the studio can create some order from the chaos of reality that surrounds and threatens. There is some echo of the paintings of Francis Bacon in the artist’s delineation of the space on which the figure sits, though hers is less formal and perhaps less starkly existential.

It’s too easy to be pretty.

There is positivity in the capable hands and strong, curvilinear feet of Cope’s figures and in the smaller nudes – reminiscent of the work of Degas and Picasso and Matisse – whose intimacy of self-possession is reinforced by the size of the canvas. One is impressed by the bodily density of these figures and the sense of decorative joy and life energy in the brushstrokes. The still-life elements in the paintings are not at all still – they explode with life and colour. In these playful paintings a high-rise building looks as if it might dissolve; flowers become fireworks; houseplants become jungles; meat on a blue dish becomes a celebration of colour.

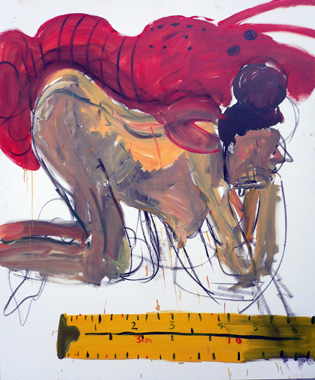

One painting sits in postmodern comment on the role of the artist – bottles, lemons, paintbrushes ranged in readiness, overseen by a flamboyant clock symbolising the tyranny of objective time and external rules and fore-runner of the measuring-tape motif in the more recent Fís nudes, which the artist refers to as the ‘menopausal’ work.

And this is the link with the Northern European tradition of vanitas – the use of objects in paintings to focus the mind on life’s brevity and the certainty of death – a tradition explored more fully in these recent monumental paintings which combine a sense of the macabre with painterly power and a vein of black humour. Otto Dix meets Henri Matisse.

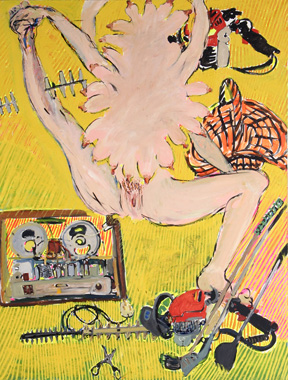

The frenetic comic exaggeration in the painting of the multi-tasking domestic goddess dancing whilst hoovering or the nude with a tyranny of twenty breasts or the skeletal male competitor holding six tennis racquets whilst the figure he is grinding into the dust grabs his scrotum, is indeed the stuff of cartoons. But the jaw soon begins to ache with its relentlessness, with its chilling and violent kinetic intensity and the spectral presence of death in the cheerfully orange drawingroom.

Yet somehow Cope manages to combine with this gallows humour – this sense of desolate inevitability – a confident use of light and vibrant colour and a masterly feel for composition and celebratory pattern which is life-enhancing. To the best of my knowledge, there is only one painting where the balance tips over into the void. Nests is a sombre piece whose white shapes superimposed onto the canvas are slightly reminiscent of the dancers in Matisse’s Dance of life. But these abstracted white shapes do not dance; they do not pound the earth with their powerful curved feet; there is a sense of inertia and absence – a palpable loss and deep sadness.

Given the subject matter and motifs in the recent paintings, it could be argued that these present a ‘feminist ‘perspective. There’s a great deal of menstrual blood and recurrent images of predatory threat and oppression. But I would maintain that this is too narrow a view.

Death squats on all our backs.

Sandra Gibson is a freelance writer living in Cheshire, UK. She has written poetry and fiction, collated and edited the memoirs of a war veteran and the letters of a reclusive monk. An article about the artist Estella Scholes was published by Art of England [May/June 2005] and she makes regular art and music contributions to The Nerve, a Merseyside based magazine. She is currently writing the biography of a blues musician and working on a piece about Mary FitzPatrick.

The work of Elizabeth Cope is widely represented in public and private places and is cosmopolitan in scale. She has worked in Central America, Somalia, Aix en Provence, and elsewhere, as well as in her native Ireland. Since 1979 she has exhibited in solo as well as group shows in various places including Dublin, New York, Edinburgh, Bologna, London, Zurich, Mexico City, Brussels… For further details consult the artist’s web site: www.elizabethcope.com. For an additional reaction to her work in the Liverpool Fís exhibition, go to www.catalystmedia.org.uk.

One image from the original article is missing here.