|

| Angela Darby: Shutter, 2007, digital print on Foamex, 80 X 100 cm; courtesy the artist |

The collaborative approach is one that is not new to these two artists; they have exhibited jointly in previous exhibitions with other themes. In this show, named Social Security, their work is a response to underlying social and paramilitary unrest in a post-peace-agreement Northern Ireland. In this era, the projected media image of the state of the Province is decidedly upbeat and any paramilitary type of activity goes unremarked. Darby and Peters present a state of underlying fear and social tension, where traces of upheaval and marking of boundaries remain as a sign of previous activity. They have used the catalogue to explain the origins of some of the works and give helpful suggestions as to how they should be interpreted, substantiating the message that the artists intend to convey.

Of the several types of media in the exhibition, it is mainly the photographic work which describes this atmosphere of social tension. Both Darby and Peters show photographs, but Darby also shows a series of embroidered slogans and Peters shows prints, tackling the subject from different angles.

There are no people in these photographs, only the signs of their actions. The dereliction and destruction evident seem all the more sinister because of this unseen human presence. One photograph of Darby’s, however, seems to symbolize the fear explored throughout the exhibition, and it is this image the artists used for publicity. It shows a closed steel shutter folded in concertina fashion; signs of fire damage appear as distractingly beautiful rust browns against the steely blues of the metal.

Peters’ installation, For everything a reason, is made up of two elements.One is a large photograph of the back garden of a recently deserted house in which domestic objects – a wheelie bin, a rotating clothesline, containers – have been left fallen and abandoned. There is a plastic-lined garden pond with stone surround, a reminder of former days of leisure when there was time to prettify the surroundings. But the whole scene has been made all the more weird by mirroring the image so that it becomes symmetrical. Where the two mirror images meet along a vertical line down the middle of the photograph strange forms appear, looking like something out of science fiction. The whole thing seems to take on a human or animal form due to its symmetry, only becoming a back garden when one stands away from the image. Beside this photograph are six smaller screenprints of patterns of small snipped pieces of barbed wire on stretched flower-printed textile, which was found in the abandoned house. The defensive thorns of the barbed wire contrast with the pastel-shaded flowers of the fabric; together with the weird humanoid domestic environment, they create a disturbing installation.

|

| Robert Peters : For Everything a Reason (Garden), 2007, digital print on Foamex, AO approx; courtesy the artist |

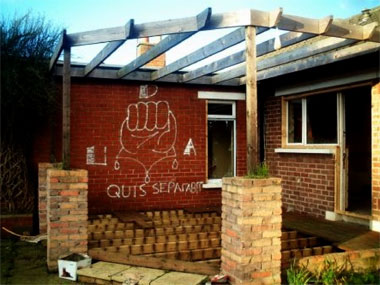

Another abandoned house features in one of Darby’s photographs, a once-respectable suburban bungalow. The view here is also of the back, looking at the dismantled wooden floor and roof of a patio, the wood having probably been donated to the local bonfire site. On the wall of the house the UDA have made their mark with their painted emblem of a fist and motto ‘Quis Separabit’.

|

| Angela Darby: Quis separabit, 2007, digital print on Foamex, 80 X 100 cm; courtesy the artist |

The bonfire site is the subject of another photograph, which shows a small caravan parked on a grassy verge in front of some trees with the sign ‘BONFIRE SITE OFFICE’; the caravan is obviously not in present use as the curtains are closed and the red, white and blue of the kerb is faded. As in all these photographs, one wonders where everyone is; are we looking into the past or is this a picture of the present?

A further work by Peters, the screenprint Imprint, develops this idea of time. It shows the looming silhouette of a gable with flag on the roof against a glowing red evening sky; on the gable is embossed an emblematic mural of the Ulster Freedom Fighters. Peters comments in the catalogue that although the stylised setting sun signifies change in communities, the legacy of the past remains. The artist has used the process of embossing metaphorically (the gable mural is not easily seen, a metallic image on black), but the fact that it is embossed suggests that it will not be easily removed either.

|

| Robert Peters : Imprint, 2007, screenprint, 20 x 25 cm; courtesy the artist |

Darby has appropriated paramilitary slogans for her own ends in a series of embroidered pieces. They are arranged together in symmetrical formation on the gallery wall. Centrally placed is the series We have no future, in which nicknames of loyalist leaders who have been rejected by their organisation and either executed or exiled – eg, Mad Dog, King Rat – are skilfully embroidered in a graffiti script and framed with coloured fabrics.

On either side are two flag-like pieces from the Bias binding series, in which the artist has taken the mottos ‘Quis Separabit’ and ‘Loyal and Determined’, working them onto flowered fabric in multi-coloured threads, bordering them in blue. Another slogan is embroidered on sackcloth using only black and white; ‘Vita Invicta Venia’ is a bastardised motto scavenged by the artist from various loyalist slogans. While sounding profound, it is in fact meaningless: the artist’s comment on Gusty Spence’s statement to the families of murdered victims.

These embroidered slogans take on a new life through the jerky movements of the graffiti-like letters; some of the words are hardly legible and become visually interesting puzzles. In using the medium of needlework, which carries with it all the connotations of the personalised, the artist has transformed these pedantic mottos into quirky, colourful emblems of her own, perhaps in an attempt to defuse fear. Loyal and Determined, she states in the catalogue, she dedicates to her working practice and Quis Separabit (who shall separate us) is applied to the one she loves.

|

| Angela Darby: We Have No Past (No Future ), 2007, fabric, bias binding and graffiti embroidery, 40 x 20 cm; courtesy the artist |

Returning to Peters’ work, two of his digital prints employ optical effects. A red square, on which are pieces of barbed wire, stands out as if in three dimensions against a background grid of blurred black dots. The barbed wire is a threat and a means of defence; it is made yet more disturbing by the visual effect of the black dots.

The second piece, Six into thirty two, is a grid of identically shaped circular dots with radiating spokes, four across by eight down. The six in the top right-hand corner are subtly different, darker in colour, and the whole rectangle is read as representing the thirty-two counties of the island of Ireland. The effect of the shapes and colours in this vertical rectangular grid is to dazzle the eye and eventually focus on the darker six counties. As we learn from the catalogue, Peters’ intention is that the tensions set up in the composition reflect the unresolved political situation.

Although generally helpful in giving the background to the works, the comments can, as in this case, restrict interpretation rather than giving an opportunity to see any subtleties in the message.

Darby and Peters in this show bring awareness to a situation in our society which is often sinister; the situation may be a symptom of fear or it may be a cause of fear, the two merge together. Darby’s embroidery seems to deal with the situation by turning it around into something celebratory.

Sally Houston is an artist working in Co. Down.