Regina Gleeson has been in e-mail conversation with Valerie Connor, curator of the Republic of Ireland’s Pavilion at the fiftieth Venice Biennale, 2003, and the Republic’s entry to the São Paulo Bienal this year. This edited interview is an accompaniment to an article in issue 109 of CIRCA Art Magazine. It took place between June and July 2004.

How did you plan for the curation of the Irish entry in the Venice Biennale last year and the São Paulo Bienal this year?

For Venice, I travelled over at the time of the Architectural Biennale in 2002 with Jenny Haughton, Ireland’s National Coordinator. I met with Ireland’s local coordinator, the monks who run the Scuola di San Pasquale which had been used the previous year as the Irish ‘pavilion’, and Francesco Bonami. I was especially curious about his ideas about the Venice Biennale, as he was involved in establishing Manifesta , which was initiated partially as a challenge to the established biennials.

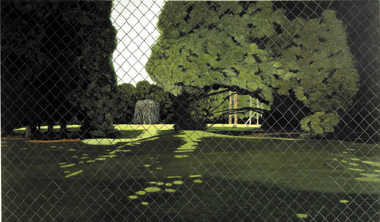

Once I made that first trip to Venice, it was really clear to me that I wanted to ask Katie Holten. My decision was informed by the building, the location, the character of that year’s Biennale as well as my wish to invest what resources I had to work with as best as I could. In turn, my proposal to Katie was to go to Venice together, and to talk about what she wanted to do from there. The whole process of discussion and planning involved a great deal of communication between all parties involved.

For Brazil, I invited the participating artists, Stephen Loughman, desperate optimists and Dennis McNulty, before going to São Paulo at all. Why? Too expensive for me to go over there in advance. Alfons Hug agreed to allow more than one artist take part for Ireland’s representation. It is the case, now, that the administration in São Paulo demands that only one artist is asked to represent a participating country. Consequently, I had to present a context for my selection, contrary to the rules so to speak, to Alfons Hug. All the artists went to São Paulo in January this year (also my first visit). This was critical in setting things up as they now stand. I was also able to introduce Alfons Hug and his staff to the artists, which was extremely important.

Katie Holten, Stephen Loughman, Dennis McNulty and desperate optimists are an interesting and exciting group of artists but not necessarily one that communicates easily and functions as a unit. There is no reason why they should, but what does their work say about our place in time?

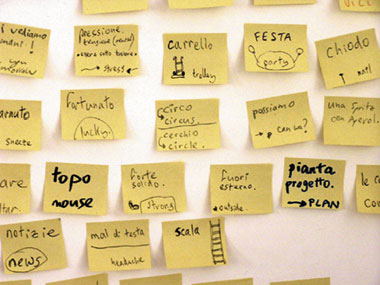

I agree that they are interesting and exciting. I think they communicate really well. They aren’t a unit. About our place in time, I think they work very much in the present. To do that they all pay heed to the past, to the history of the images they make. They have all become skilled at what they do, and have learnt and use techniques that enable them to intervene in and take part in the world ‘of signs’. These people work consistently at what they do and re-affirm that individual or discrete practices are not hostile to the conditions of culture at-large while focusing on the conventions attached to their media. I think this says good things about our place in time.

There are innumerable problems associated with cultural categorisation by nationality. This is partly because of the changing landscape of shifting cultural influences and identities and largely because of the difficulties of how to deal with the break-up of nation-states into fragmentary non-places or new places with ‘foreign’ national identities which a population is expected to assume. Further to this is globalisation’s magnetism that often relates cultural accents to a kind of central value or median which creates adjustments with regard to the relevance of national identity. Can you say how you feel any or all of these elements affect or informs the work of the curator?

Nationality may appear to be a non-issue under the ‘shifting’ terms alluded to above. However, we have only to look at the recent Citizenship Referendum in Ireland to realise that it is still something that the enfranchised value as something to be ‘protected’. On this point, I think it’s worth remembering that on the same weekend the fiftieth Venice Biennale opened, there was a referendum on whether the laws in Italy governing immigrant labour should be changed in order to compel immigrants who were more than two weeks unemployed to be deported automatically. The Italian referendum generally wasn’t something that was spoken about during the opening days.

I don’t think national identity is something that is no longer an issue. But it is not the only issue. And it is no longer an issue based on unproblematic universalist ideals of citizenship attached to the best principles of liberty, fraternity and equality…especially fraternity…

I mentioned earlier that, for Brazil, I made an argument to the curator Alfons Hug that sending one artist was problematic – because it exaggerates the emblematic value of artist and their work alike. Emblematic of a kind of work, a kind of approach, a kind of success around which there is some imagined consensus representing a highly abstracted measure of excellence or work at the zenith of zeitgeisty now-ness. Or, it could be perceived to be about the attribution of supreme value by one individual (the curator) to another (the artist). All in all, a creeping connoisseurship can easily get a foothold in a show where one nation is represented by one artist – I think.

Both Venice and SãoPaulo require that you work as a curator of a small section that is a part of a bigger show under the curation of a senior curator, Francesco Bonami in Venice and Alfons Hug in SãoPaulo. How much restraint or control do the senior curators allow to the curators of sub-sections of the exhibition?

Both Francesco Bonami and Alfons Hug engaged with my ‘wants’, with Bonami suggesting possible spaces and basically being helpful in an advisory way, and Hug consenting to my wish to include more than one artist.

Much of what Francesco Bonami’s curatorial statement was pointing to involved celebrating the politics of marginality, peripheral art practices and the role of spectacle in the socialisation of audiences and I couldn’t resist responding to this thematic statement. With Brazil, my response to Hug’s ‘images smugglers’ theme is, in a pretty straight forward way, played out by my inclusion of more than one artist and, moreover, the inclusion of different sites of distribution for their work. I’ve been pleased to be able to present work that, while perfectly legitimate in the context of such an international exhibition of art, is usually separated into more medium-specific events…film festivals, electronic-music festivals and so on.

Many curators describe their work as being that of a facilitator so, perhaps without using the word ‘facilitator’, how would you define your job as curator?

While it’s about facilitation it’s much more active than that might suggest – more ‘directional’. My job as a curator is about having an overview of all the factors that will impact on the production of a piece of work, whether a new commission or the installation of an existing work. It’s figuring out the politics of complicity, taking a positive attitude to contingency in the pursuit of a project, understanding power and how this knowledge is at the heart of ‘culture’. It’s about making sure that everyone involved in producing a piece of work or a show knows to what ends their effort is directed. It’s collaborative: the belief it’s anything else is a cod. It’s about knowing what history is, what art is, what communication is. It’s a position of privilege – assigned not assumed. It’s tenuous. It’s fun. It’s interesting. It’s necessary. It’s an education.

As well as negotiating what is shown in an exhibition, a curator mediates that which is not seen. Where do you think the responsibility of the curator ends ?

Read ‘control’ for ‘responsibility’ in the question and I think that gives an insight into the dynamic that the question ultimately interrogates. The omission of work from a selection, programme or show is always a decisive thing to do and it simply doesn’t happen by accident for no reason and there are always consequences. But in terms of mediating what is not seen, a curator’s working relationship with technical and administrative colleagues is not seen. These relationships create a highly mediated environment. This is the primary site of mediation that will make or break the potential to produce a project or programme.

In the cultural sphere, do you think the curator determines the brand of Globalism with which we are confronted – homogenised or multi-cultural melange?

I don’t really understand Globalism as a brand, and multi-culturalism is a controversial term now. But yes, I think that curators who have a high profile and are mobile have a huge influence on creating the impression that art – that they choose to show – is equally valid in the same way the world over. To expect to measure validity on a global scale here is not ridiculous because, of course, international art exhibitions – including the proliferation of biennials – provide a repeatable and stable institutional framework that allows for the work on show to be seen in supposedly equivalent conditions. I think that’s the premise. And to a great extent therefore the reception of the art can be determined by the will of others, the curators in question.

From your experience, what part does the curator play in this process of making sense of what appears to be chaos or at least in finding ways to communicate and live in such intellectual and cultural chaos?

I don’t know if the figurative meaning of chaos, or cultural chaos, is an optimistic way to look at the purpose of making sense of things (or globalisation, by association in this context). Maybe the popular attraction to the pithier metaphors and narrative examples used by physicists who developed the science of Chaos theory says something about both the joy of connection as much as about the perils of causal relationships. I think that a curator interested in making sense of things needs to spend quite a lot of time getting to grips with what compels us to do that, or to think that that is the most valuable thing we can do. I can appreciate that this poses a dilemma in terms of where a person finds that time. Curators, like anybody, have their personal finance to deal with. Most curators (of contemporary art) would not – I would be quite sure – be paid to undertake self-directed periods of research ‘out of the office’ or outside the usual terms of a contract. This kind of on-going research – that should be so important – doesn’t get formally acknowledged as a rule, as part of what it is that a curator does or is for. I guess, it’s an example of ‘what is not seen’ (question 7).

Multi-disciplinary collaboration is a strong contemporary method of working in fine art. Much collaboration loosely forms around the guidance of an artist functioning as a director. Could it be that the artist of the future is a curator ?

I think the curator of the recent past is an artist. Lots of column inches and talk time some years back were about the artist-curator. I think too that historically artists have ‘curated’ their own work and other people’s (in Modern times). I personally work as a curator using the principles I learnt and used as an artist. I’m not troubled by some psychic or existential difference on this issue. It’s just a part of an art practice as such. It’s not a mystery…which doesn’t diminish creative pleasure. I accept that’s not going to be everyone’s experience. Obviously.

Valerie Connor is curator of the Republic of Ireland’s Pavilion at the fiftieth Venice Biennale, 2003, and the Republic’s entry to the São Paulo Bienal this year.

Regina Gleeson is a writer on art and technology. She has written a series of articles, collectively titled Dislocate, renegotiate and flow, for CIRCA issues 107, 108 and 109. You can read the texts of the 107 and 108 articles here and here respectively.