‘What is to be done?’ was the question ringing in everybody’s ears in hollow tones following the Communism exhibition held at Project in Temple Bar, Dublin, in January and February this year. This was a show that brought the dialectics of aesthetics and ethics to the fore and invited the audience to contemplate past, present and future alternatives to our contemporary world. Ever since the 1960s, when the creation and reception of works of art began to be concerned in a major way with social change, we have grappled with utopian ideas of one sort or another, with activist art springing from racial and sexual politics, and with the ideas explored in the wake of institutional critique. Grudgingly or not, most people would agree that the revolutionary days of 1968 and their aftermath have dissipated, and thus the tone of the Communism show was necessarily balanced although teetering on the edge of ridicule: the juxtaposition of a re-enacted Dadaist performance by Lali Chetwynd and Goshka Macuga with a Lenin impersonator reading a speech in German, or the totally uninhabitable maquette of a commune by Klaus Weber, seem to sum up the out-dated term that is ‘Communism’ in our times. Our contemplation of the death of this term leads us eternally to the question quoted above, and judging from the public’s response to Susan Kelly’s installation which posed Lenin’s question (a roaming questionnaire shown as part of Communism ), everybody and nobody has the answer.

|

Pierre Huyghe; Streamside day, 2003, event, mixed media, film and video transfers, 26 minutes, colour and sound: courtesy of the artist / Marian Goodman Gallery, New York/Paris / Irish Museum of Modern Art |

It would seem that nowadays a world filled with four billion people and free trade complicates our ability to comprehend alternatives or improvements. While the status quo of neoliberalism may be abhorrent, it is fairly firmly entrenched, and for artists such as Pierre Huyghe it is rather a question of utilising or subverting its forms nowadays to produce a new reality. For this reason, Streamside Day by Pierre Huyghe, now showing at IMMA, provides an entanglement of reality and fiction that could be one artist’s fantastical response to Lenin’s question / lamentation. In a recent interview in October magazine, George Baker explicitly demanded that Huyghe define his political position, asking if it is “a realisation that false political claims for artistic practices were made in the 1980s, and [that] one must not falsely claim immediate political functions for cultural or aesthetic projects?" To which Huyghe replied that “It is obviously difficult to define oneself after a post-modern period where we all became extremely self-conscious and aware about the consequences of our actions. This is why conclusions should be suspended but the tension should remain. There is a complexity that should be recognised and that should produce a fragile object."[1]

When this film was originally screened at DIA:Chelsea, New York in 2003, it was billed to be a “celebration and a resulting film work," placing some emphasis on the initial event that was Streamside Day . Huyghe advertised for participants to take part in a celebration to mark the creation of a new suburban settlement on the Hudson River in upstate New York called ‘Streamside knolls’. For this the artist designed the framework for the day, including a parade with animal costumes, a flautist and trucks, along with a feast consisting of such American classics as hotdogs and corn on the cob and a Streamside day cake. The activities were then set in motion without a script, recorded by the artist and projected as the second part of the film and titled ‘A Celebration’. The film is shown in two parts: the first is called ‘A Score’ and the second ‘A celebration’; the former title could be a reference to the influence that John Cage had on the early Happenings of Alan Kaprow and the concept of setting in motion a social sculpture as one would a work of music. The second part of this film was shot in documentary style with a progressive and consistent narrative that seems to span the length of a ‘perfect’ day, of which we are the posthumous spectators. The children are the main characters in this pageant that is packed with corny references; the flashing lights of a parked police car serving as disco lights is a case in point. Initially there is a saccharine sense of the comfortable middle-American ideal – people from many different backgrounds moving to a new settlement and celebrating as every new migrant community in America does – by holding a parade. But other factors serve to complicate this which are, unfortunately, not so evident in the piece as it is presented at IMMA today. In its original form the installation was called Streamside Day Follies and was presented within a temporary-looking folly-like structure that would slowly arrange itself before each screening of the film in a mournful or graceful movement (on wheels) and slowly deconstruct itself afterwards. A folly is usually an ornamental building and not functional at all – in contrast with the houses that are being built in Streamside knolls which are soon to be inhabited by families.

At rest the panels that made up this projection room blended with the white walls of the gallery space, but on the reverse they were an iridescent green that created an emerald-city effect when the ‘folly’ was in place. This construction and deconstruction of the projection-room folly is reminiscent of the constant flux of the building site, the evolving nature of which has great significance in the oeuvre of Pierre Huyghe, in particular what he defines as the permanent building site (‘chantier permanent’). In his project of the same name, he documented the many half-built buildings surrounding Naples and Rome that circumvented tax legislation by never reaching completion. These buildings are often constructed in their owners’ spare time without proper plans or an architect and their significance for the artist is their open-ended or never-ending nature; they exist with the sole purpose of being eternally created. To some this would appear to be a frustrating undertaking, a sort of Catch-22, but this dialogue between the finished narrative and the open-ended text allows for endless possibility.

The fragile object that is the work of art as defined by Huyghe is not explainable in terms of public or private space but in terms of the ways in which we make use of them. We are afraid that the totalitarianism of a communist regime or the conspiracy of business interests will lead to some Orwellian nightmare, but we wonder if the cultural sphere is the correct venue for these fears. While we try to figure these things out, people are getting on with living and appropriating spaces and creating new realities from spectacles. The film twists our modern commercial understanding of celebrations too, as this is one which, rather than being appropriated by business for the sake of product sales, has been created from day one in a modern vernacular. By way of explaining his fascination with commercially appropriated celebrations, Huyghe has spoken about Hallowe’en, which he sees as a celebration that has lost its significance for the many people who have no idea that it was originally an Irish pagan feast that sits uncannily close to the Christian All Soul’s day and the Mexican Day of the Dead. Streamside Day attempts to create a feast that examines the ‘pagan’ in our contemporary situation.

Streamside Knolls is a private development and an instance of private and commercial interests moulding our civic space. The privately built public or civic environment has recently become a major feature of life in Ireland, the IFSC development being a case in point, while in America it is much more common. These private or public-private ventures are currently seen as the modern face of progress. However, as the sole objective of the dialectics of progress, to use Marxist terms, is the maximisation of profit and the intensification of control, we must be suspicious of the celebration of such acts as depicted in Streamside Day . With this film Huyghe tackles these issues head-on; for the artist it doesn’t matter who is creating the civic space, it is rather a question of how the inhabitants appropriate that space.

|

Pierre Huyghe; Streamside day, 2003, event, mixed media, film and video transfers, 26 minutes, colour and sound: courtesy of the artist / Marian Goodman Gallery, New York/Paris / Irish Museum of Modern Art |

At DIA the projection was accompanied by plans on the wall for a community centre for the Streamside settlers created in conjunction with the architect François Roche. Of all of the arts, architecture is the one that is the most consistently utopian, although in these terms Huyghe has managed to touch on one of its more negative nerves by referencing the ‘architecture as entertainment’ ethos that is inherent in the word ‘folly’. This is one instance of the tension that the artist spoke of in the October interview. That is not to say that an absence of functionality is negative in general, but in this instance we are supposed to be contemplating the new homes of a new settlement, and thus a tension is created between the functionality of the housing and the wistful nature of the design for the community centre. This community centre is to be built in the heart of the forest near the settlement: “…forest of myths, of origins, playing out the complexity between what is within, without, on the edge in various movements. Its layout would mix human activities with wild fauna, domestic fauna like a fold between a here and now situation and a naturalist artificial construct." The concept of this community centre almost literally references the Garden of Eden: “One must imagine a portion of territory in a cage, not like a zoo but like a place where the animals within are the same as those without, although domesticated."[2]

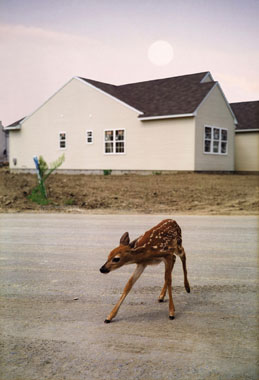

One gets a sense of this concept of a forested idyll from the woodland creatures and the fawn that tentatively explores the settlement in the first part of the film, ‘A Score’. This ‘Score’ seems to lay out the sentiment of the film as a whole; it is allegorical rather than literal and is less consistent in terms of narrative structure than the second part of the film. In contrast with the second part, which was unscripted and has the air of a documentary, this first part uses more emotive and formalist camerawork. The almost overwhelming forest, which is contrasted with the children standing before it, seems to engulf and yet bolster up those who approach it. At IMMA, the audience can make the association between the forest and the architectural drawing on the wall outside of the projection room, as the small children are depicted in both, their size contrasted diminutively. The drawing seems to literalise Huyghe’s interest in the Baroque fold, another of the artist’s anti-teleological gestures that was just one of many in the repertoire of the French philosopher Gilles Deleuze.

It is a pity that the piece is not doing the rounds in its earlier ‘DIA’ form.

The projection of video work since the 1990s has left us with a legacy that submits the viewer to a passive position not unlike that which we take up before a painting. Streamside Day in its original form would circumvent that position, as the audience had to move around in order to take up their temporary place before the projection. The plans for a community centre for the inhabitants of Streamside were an important means of engaging with this video and added to the open-ended nature of the work. At IMMA, the projection room is completely fixed and traditional, although the walls have been painted a very dark green with reference to the forest; thus we have been returned to our traditionally passive role in relation to the artwork. The only reference to the architectural plans for the community centre is a drawing outside of the projection space without explanation. In Dublin we have been presented with the scaled-down version of a portion of a more complex project, and the spatial nature of the work is lost, placing much more emphasis on its temporality.

[1] George Baker, An Interview with Pierre Huyghe, October 110, Fall 2004

[2] Carolyn Christov-Bakargiev, Pierre Huyghe: Through a looking glass, Pierre Huyghe: Float, 2004

Sinéad Halkett