Amidst a forest heavy with insect noise and seemingly outside of historical time we come across an idyllic scene of a young fawn, a rabbit, an owl and a raccoon innocently going about their business. Other than a thundering waterfall, this is all sunlight through leaves, babbling brooks and twitching noses: a rather saccharine nature, then, not wild but tamed, and purged of death, violence and decay. The colours are overstated and the animals pose harmlessly for the camera in this fabulous setting straight from the wonderlands of Disney.

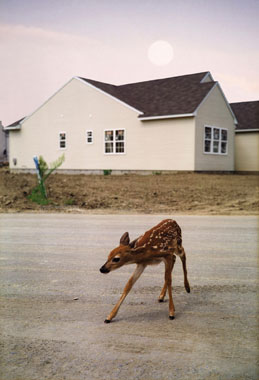

We follow the fawn to where the forest meets the barren earth of an incomplete suburban housing development. This is the frontier of a different territory – partitioned, well managed and privatised; in short, Middle America – but the time that marks out this territory is the same as that of the fabulous forest; it is a temporality where memory, reality and history converge in fiction. As Huyghe says, “We are in the year 01, the beginning of a story which you are already a part of. Between the mountains and the Hudson River, a village is forming in the forest. Families are moving in, construction of streets and houses is almost complete, gardens are growing, and soon the playgrounds will be filled." This ‘story’ is as pre-historic as the forest, because it begins again by restaging a mythic past in the present in spectacular form, and so tells the same old story.

|

Pierre Huyghe; Streamside day, 2003, event, mixed media, film and video transfers, 26 minutes, colour and sound: courtesy of the artist / Marian Goodman Gallery, New York/Paris / Irish Museum of Modern Art |

As the fawn makes its way along deserted streets, we switch to a family en route to their new Streamside home; and whilst fawn easily becomes cuddly toy in the hands of a child, momentarily, as the two blond-haired young daughters dither at the edge of a Romantic forest, a transition is made in the other direction, from Disney fable to the older, darker tales of the brothers Grimm. And as the girls confront the towering foliage of the Urwald, a spectre emerges: one associated with the nostalgia for a communal being fused under a common image, to be regained through the restoration of mythic and organic origins; or more precisely, one that sanctifies the tribal territory as the mythic source of vitality and displaces the responsibility for tribal conflict to the impersonal play of ‘organic’ forces.

This spectre is familiar enough, but here its darkness is short-lived. The second half of the video, A celebration, develops from this mythic core, as we observe the inaugural Streamside Day festival, with speeches from the ‘town supervisor’ and ‘economic developer’, a song from the town ‘bard’, children and adults dressed as animals; dancing, donuts, burgers and a fire engine. It has been claimed that Huyghe is fascinated with “communal rituals as an agent of change, growth and the evolution of society." But, although running through this celebration there are the residual elements of rituals and desires played out at the edge of nature (evident, above all, in the activities of the children), these desires are overridden by the spectacular images representing this nature. And, as spectacle, the celebration is as much predicated upon an accumulation of capital as it is some nebulous communal ambience. We witness the development of ‘communities’ that are “as much the recognition of marketing concepts as they are the building blocks of the public sphere." (Rachel Thomas) So, we should be wary just what type of ‘growth’ and ‘evolution’ these communal rituals are agents of. If the principle of communal self-preservation, which should lead “by its own force to the desideratum of happiness," becomes a fetish the community remains infantile. If the suburban ‘pioneers’ become spectators of their own desires, they renounce the development needed to find their satisfaction in lived experience and develop false needs instead, which are satisfied in a world of real images: “For one to whom the real world becomes real images, mere images are transformed into real beings – tangible figments which are the efficient motor of a trancelike behaviour." (Guy Debord).

The world as spectacle induces ‘trancelike behaviour’ that detracts attention from the group interests and power relations crossing social rituals and the production of representations. But who is in a trance? The characters in the celebration are actors or members of the public invited to participate: they know they are taking part in the fiction of their own representation, and hence, their alienation, which would be increased by the transformation of lived experience into spectacle, seems rather stretched. To what extent then does Huyghe second-guess the Situationist claim that art is incapable of expressing anything but alienation? Does an audience that participates in the structures of its own representation, but does so only in a fictional environment, simply pre-empt its own alienation? The artifice of the event was surely understood by the participants from the start; but is it so immediately apparent to the audience of the video who perceive it as a documentary?

Huyghe returns art to the status of the “fictive language of a non-existent community" (M. Rasmussen) and this fiction is precariously maintained in that ‘non-place’ of film, somewhere between real time and represented time. This position of film makes it a suitable medium for spectacular representations, of course, but it also offers the creative possibilities which allow Huyghe and his collaborators the attempt, similar to the surrealists, to re-consecrate human relationships vis à vis the poverty of the spectacle. He does not, however, re-consecrate art as the privileged vehicle of representation: for all that Huyghe’s ‘connective images’ have been said “not to represent the world, but to place us at once within and outside the processes by which we visualise and construct our realities," he still seems suspicious of art’s capacity to articulate the elements of an authentic life.

A common belief is that artforms developed through direct, nonalienated interaction will not reproduce divisions of labour prevalent elsewhere; that they will return social relations to an exchange between producers, not commodities. But Huyghe seems aware that these forms of interaction must pass through the assorted fictions of representation, making community itself a commodity to be consumed by the members of that community, and as such these forms all too easily participate in the organisation of social passivity. Again like the surrealists and their practices of ‘free’ representation, the attitude that posits art as the privileged means for fantastic enactments of community would likely be a welcome component of spectacular consumption; “the aim [of the latter] being that the proletariat should move only to the extent required for the contemplation of its own inert contentment, that it should be rendered so passive as to be incapable of anything beyond infatuation with varied representations of its dreams." (Jules-François Dupuis).

This ‘infatuation’ is evident in the Streamside community members as they determinedly celebrate their dreams, all the while committed to an “absolute valorisation and preservation of the present moment." (And certainly, this proletariat, if it is worthy of the name, is not moving anywhere: as to the ‘contemplation of its own inert contentment’, we might recall that the invitation to the public to participate made much of the food and spectacular events that would be available, as well as, simply by virtue of being a renowned artist, the ‘unquestionable’ benefits of HuygheÕs collaboration with the community.)

|

Pierre Huyghe; Streamside day, 2003, event, mixed media, film and video transfers, 26 minutes, colour and sound: courtesy of the artist / Marian Goodman Gallery, New York/Paris / Irish Museum of Modern Art |

But although Streamside day refuses to lay claim to the representation of an authentic life, it does not then participate fully in the spectacle. Like the two young girls, it dithers at the edge of fact and fiction. It mediates both through its own structures, privileging neither, but showing rather that each must pass through the other for it to be known at all. How effective such mediation can be as a means of either deciphering ‘our systems of social exchange’ or ‘exposing reality’ is an open question. Yet the subtle complexities of HuygheÕs narrative structures undermine the fictive spectacle as much as they do the authentic fact, and for this reason his work cannot be dismissed as just another politically tame practice ‘spiced up’ by its description within Situationist terminology (we must remember, however, that there is a more general problem in aligning institutional art practices with the Situationist belief that art had to be realised outside its institutions in a creative, everyday life: that, in the words of Guy Debord, “[only] the real negation of culture can inherit culture’s meaning. Such negation can no longer remain cultural . It is what remains, in some manner, at the level of culture – but it has a quite different sense.").

Streamside day seems to have more in common with the activities of Laibach (a subgroup of Neue Slowenische Kunst), who, rather than attempting a critical or ironic distance from their subject matter (i.e. the inherited state ideology of the post-Communist Balkans) – seeing irony in particular as not so much a threat to the system as ‘the highest form of conformism’ – instead make an excessive identification with it, thereby showing the ‘obscene’ other side of this ideology and suspending its efficacy (Misko Suvakovic). This would mean that Huyghe’s celebration of contemporary folklore and tradition and the recurrence of spectacular communal rituals would be a more radical form of art praxis than it appears, at work in the most unlikely place.

Tim Stott is a critic based in Dublin.