On 30 January 1972, soldiers from the British Army’s 1st Parachute Regiment opened fire on unarmed civilian demonstrators in Derry. Thirteen people were killed and a similar number were wounded. The march, which was called to protest internment, was illegal according to the British authorities and the government-appointed Widgery Tribunal exonerated the soldiers of any guilt. After mounting pressure on both sides of the Irish Sea, an official inquiry into what actually happened that day was opened in 1998 under the custody of Lord Saville. It continues even now, more than thirty years after the shootings. Alongside the bombings in Dublin and Monaghan, Enniskillen and Omagh, the tragedy of Bloody Sunday has come to be seen as a defining moment in the history of the Troubles.

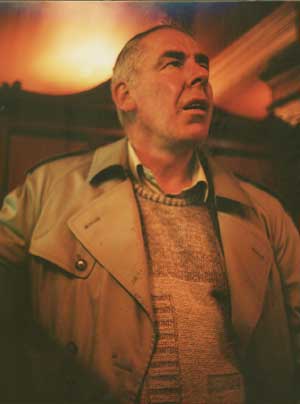

The British photographer Paul Graham first visited Northern Ireland some twelve years after Bloody Sunday, provoked by a niggling sense of injustice at how the political and military situation was being handled in the province, only to return with pictures no different from those that regularly adorned the national press on the mainland. Towards the end of a subsequent visit, Graham was stopped and searched by an army patrol, irritated by his presence on the Andersonstown estate on which they were operating. In Ulster, the armed forces have a profound distrust of photographers who have an annoying habit of being in the right place at the wrong time. Graham was released after questioning and advised against taking any more pictures. However, as the patrol was moving away into the middle distance, Graham contrived a hurriedly taken photograph with the camera positioned against his chest, pointing the lens at the rapidly dispersing soldiers. Back in London, he found in that one image the solution to all his aesthetic frustration. “It wasn’t how you were supposed to frame the action in those situations," he confesses. “I wasn’t close up. I hadn’t zoomed in on any incident, things were distant and scattered. I’d returned the action to its context. It broke many unwritten rules [of documentary photography]." 1

Roundabout, Andersonstown, Belfast was the first of more than thirty images of a strife-torn Ulster that Graham accumulated over a two-year period that avoided the clichés of sensationalist urban mayhem, concentrating instead on what the photographer refers to as the visual footnotes of the conflict. Pictorially, each of the photographs features at least one index of the cultural and mental attitudes that divide Northern Irish society. Compositionally, they span two different genres: the politically driven reportage tradition and the politically neutral aesthetic tradition. “At first sight," Graham explains,

[the photographs] seduce you into viewing them simply as landscapes which accounts for people’s desire to engage with them. But they’re booby-trapped and launch the viewer into another area altogether. They play off that particular kind of sentiment which (Britons) have for landscape – a position which engenders Constable-like fields and Turner-like skies – against sentiments associated with political allegiance, British and Irish. If you don’t delve any deeper, you might see only the flags, signs and graffiti. But these symbols should also be read within the context of the landscape in which they reside, the Union flag in the richest and most fertile lands, the Irish tricolour against the rockier and hillier ground. These different layers of reading within the photographs only come out slowly.

Troubled Land, arguably Paul Graham’s most controversial body of work to date, set itself the task of examining the condition of Northern Ireland at a time when the Troubles were at their most turbulent. In the 1980s, the reception it received was often clamorous.

People [were] much more divided about its worthiness [than about previous work of mine]," says Graham, “because the debate about Northern Ireland [was] much more divisive. Here was I, a naive British photographer with no special knowledge of the situation, going over to Ulster to make work. That got a lot of people’s backs up, not just in the North, but also over here [in Britain], people who felt that this was their territory and that the only politically correct attitude was ‘Troops Out’.

By 1987, the year in which Troubled Land appeared in book form, Graham had begun to sense that his approach to photography – a cool approach that spawned a neutral, seemingly styleless style – might profit from a degree of revised thinking. A fellowship at the National Museum of Photography, Film and Television in Bradford in 1989 offered the photographer a chance to review his practice and became the springboard for an examination of how the echoes of local and regional history were playing themselves out across late twentieth-century Europe.

The preface for In Umbra Res, printed to coincide with the conclusion of the fellowship in 1990, includes an Irish saying of unknown origin:

If you find yourself in a dark place, without any light, and the night is upon you, and should you try to look directly at something, no matter how big it is, no matter that you know where it is, you simply cannot see it. However, if you avert your gaze from the centre, if you look to the edges, using the corner of your eye, the periphery of your vision, you can begin to make something out. 2

‘In Umbra Res’ translates as ‘in the shadow of it’ and the sixteen photographs in the series tackle the problem of picturing the Troubles indirectly. Instead of Graffiti, Ballysillan Estate, Belfast, for instance, Graham fixes our gaze on ‘Religion’ graffiti in unemployment centre; rather than Unionist poster on tree, County Tyrone, he asks us to contemplate a Man watching TV news report of lynching, Belfast.

Troubled Land engages with its subject surreptitiously. The social, political and cultural tensions that Graham exposes appear in the middle-distance or off to one side of the frame. The viewer is made to work to find the point at which townscape or landscape come together with the fallout from the Troubles, the locus at which the complex layers of meaning converge. This lateralism is taken several stages further in In Umbra Res . We only know that the man is watching a televised broadcast of an horrific attack because Graham mentions this in the photograph’s title. Likewise, we only recognise that the graffiti on a telephone table is religious and that that table is in a job centre because Graham tells us so.

In Umbra Res marks a turning point in Graham’s work, a watershed which the photographer himself identified in an interview from the mid-1990s:

Photography is a medium with a unique and particular link to reality. Previously there was no problem about this, the world was out there, and you simply had to put your camera over your shoulder and go out with an open heart and head to observe this reality. This was the ‘old consciousness’ if you like. The problem is that over the past two decades our perception of reality has changed from something ‘out there’ to something ‘within us’, a blend of external, internal, past and present stimuli, personal and collective beliefs, mediated and original ideas… 3

Troubled Land was the last group of photographs by Graham that dealt exclusively with the veneer of the visible world. With In Umbra Res, and the New Europe book to which it gave rise, the photographer argued for a more holistic, psychologically charged version of reality – fragmentary certainly, but one that takes account of everything we carry with us as intellectual and emotional beings. Since Bradford, Graham has struggled to move his profession beyond the realm of simple observation:

We need people who will bend the medium to their aims, to use it, force it into uncharted territory, yet remain committed to it for itself. That is where my passion is, that is where I want to work, those are my goals. 4

Unhelpfully, the Troubles have sometimes been portrayed as taking place in a small corner of a small island off the landmass of Europe. By incorporating images from In Umbra Res into New Europe, Graham brought an apparently domestic squabble back into the mainstream of political debate. The conflict that once made of Northern Ireland the murder capital of the continent thereby took its place on an agenda which includes the rise and fall and rise of fascism, the rise and rise of the sex industry, the worsening narcotics problem, the demise of communism and the increasing hegemony of capitalism and consumerism – the topics, in short, which present the Old World with many of its sorest headaches.

For someone who had tried to engage with the circumstances in Ulster for the best part of a decade, it seemed apt to Graham that he should return to the province in the spring of 1994 to see whether he could generate a telling response to the fragile truce that properly stayed sectarian killings for the first time in nearly a quarter of a century. Hugh Stoddart says of the images produced in the first week of that previously unimaginable cease-fire, which were shown just once in London in November 1994, that it is perhaps no longer an issue “amongst habitués of contemporary art galleries that the title accompanying a photograph is part of the artwork." 5 But in the case of the nine large skyscapes that Graham shot in the three-day cessation of hostilities, out of which the more lasting peace of today has emerged, the importance of titling and Graham’s elliptical take on issues of socio-political and cultural concern were pushed to their furthest extreme.

The Untitled (Cease-fire) series depicts skies above notorious problem spots in Northern Ireland. Some photographs show cloudless skies so pale they seem almost white. Others reveal forbidding thunderheads. “Walking close to these photographs," comments Stoddart,

you see the tiny title cards contain the names of places in Northern Ireland. Newry, border town, has a black sky, full of storm. First jolting revision of perception! Secondly, each piece is subtitled ‘Cease-fire, April 1994’. Second jolt! Suddenly, we read these images with a powerful additional layer of meaning. These immaculate prints, these stunning skies are suffused with feeling… When the cease-fire was announced, Graham went back (to Northern Ireland) and turned his camera upwards. It’s a simple yet brilliant thing to have done. No borders up there. No images of death and destruction. Rather, the sky is an emblem of freedom, and of renewal (rain and sun) and eternity – a dimension against which the suffering might one day seem to have been a mere blip of misery. The longer I spent in the presence of these pieces, and let the names (Shankill, Ballymurphy, Bogside, Newry) roll through my mind, the more moving I found it.

Of course, we can never be quite sure that Graham photographed each of his skyscapes during the course of that historic cease-fire. Nor will we ever know whether they were taken where they say they were. All that has to be taken on trust. But then again so, too, do the promises that all sides are now making in trying to find a decisive solution to the region’s ills. As Graham has said, those three days in the mid-1990s are probably the most significant in the whole history of the Troubles. “Momentous times can be tranquil," he points out. “[And] peace is beautiful."

Paul Bonaventura is the Senior Research Fellow in Fine Art Studies at the University of Oxford and a Visiting Scholar at the New York Academy of Art.