Season of mists and mellow fruitfulness! Close bosom-friend of the maturing sun

Ode to Autumn, John Keats, 1819

This show was presented at Thisisnotashop, Benburb Street, a versatile not-for-profit gallery space dedicated to exhibiting the work of emerging Irish and international artists. Right on the LUAS line and spread over two rooms, the gallery captures a mobile audience of LUAS riders every ten minutes, creating a moving-image experience for those within that seems appropriate to the eclecticism and dynamism of its programme.

Despite first appearances of modesty, Orla Whelan’s exhibition We live to see each other evoked an array of readings that appealed to both the logical and the emotional in this viewer.

Characteristically for the artist, five small-scale works were hung in a measured way with space to breathe individually, yet soliciting a collective reading in open-ended narrative. The series was yet another shift in this artists’ oeuvre, her palette having become warmer and imagery more present than in her 2007 exhibition Outside at the Goethe Institut. Whelan’s use of colour and scale suggest a poignant intimacy that is both tactile and visual in its expression. While her surfaces are highly finished, her treatment of the paint creates soft luminous focal points that draw us into a world of half-light, a place where we might surrender our visual reading of the world and where the senses of touch, smell and hearing might come to the fore. Images emerge in ethereal limelight as almost amorphous, without edges, hovering between two- and three-dimensional space with a suggestion of imagined spaces and figures.

Whelan’s habit of creating just slightly off-centre focal points generates a niggling discomfort for the viewer, upsetting conventional compositional expectations, that is at odds with the misty allure of her warm tones. In looking we are decentred in a manner that establishes the artist’s presence and the notion that she is allowing us an over-the-shoulder glance into her private world. A pervading sense of uncertainty in the works provokes us to question what exactly we are looking at and so to endure with the works, allowing meaning to evolve.

|

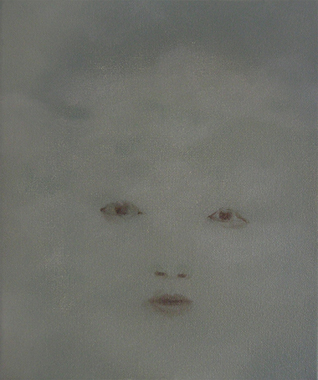

| Orla Whelan: A death foretold, 2007, 30 X 25 cm, oil on canvas |

This ambiguity is equally present in her imagery, which oscillates around the connections between nature, humanity and temporality. In A death foretold, we are confronted by the features of a child emerging surreally from clouds gazing directly at us, with lips parted as if in wonder. There is doubt as to whether this face is an apparition or part of a larger human form, with the suggestion of a life as yet unborn or in a state of becoming. The face bears the appearance of sentience and yet appears as if on the cusp of fading from our view. This piece in particular seems to bear the title of the show, suggesting Lacanian notions of the gaze and the formation of the subject – that in our engagement with others and the world the most immediate senses of touch and sight are activated. Through sight we are ever reminded of our separateness and thus seek to reconnect through touch and speech. However, for this hovering face, the possibility of reconciliation is suspended.

|

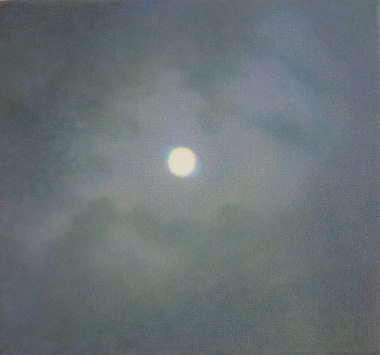

| Orla Whelan: Moon I, 2007, 23 X 25 cm, oil on canvas |

|

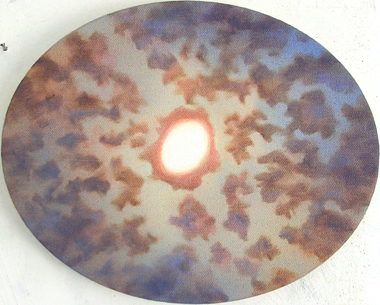

| Orla Whelan: Moon II, 2007, 20 X 25 cm (oval), oil on canvas |

Moon I, a full moon depicted through breaking clouds, slightly off-centre on a not-quite-square canvas, is accompanied on the same wall by another skyscape, Continuous, describing a broken-clouded but sun-streaked sky. Both sun- and moonlit skies have us gazing upward to the heavens with an awareness of a larger universe beyond. Both light and reflection seem pertinent here, and one finds references to earlier periods of painting, eg the work of the German Romantic era and seventeenth-century Dutch nocturnes. Moons I, II and Continuous suggest fragments from Friedrich’s evening and night scenes. But where Friedrich’s Rückenfigur [1] or solitary viewer is diminished by the landscape, Whelan places the viewer outside the frame to reflect on scenes of the natural world that are human in scale, yet not quite representational, reinforcing our sense of yearning detachment from the larger order of things.

|

| Orla Whelan: Continuous, 2007, 25 X 33 cm, oil on canvas |

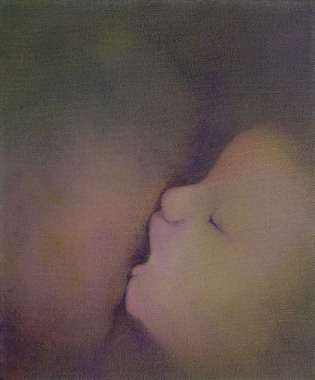

In contrast to Moons I and II, Continuous hints at human presence, suggested by buildings on the low horizon but, as with the former images, the emphasis is placed on the primary light source and cloudscape. No light emanates from the buildings, which seem muffled and inanimate in a compacted mid-ground. Moon II, a small oval canvas on the opposite wall, hovers visually between an eerie oval moon and a portal of light, in a trompe l’oeil ceiling, but minus the putti and architectural features, as if hesitating on a suggestion of the celestial. In the rear room of the gallery the final work upsets any frame of meaning that may have already been settling around the other works. It seems as if the artist has kept the most difficult image until last. Child seems to portray a child suckling on a breast, but again the imagery hangs nebulously on that proposition. Warm skin tones emerge from a darker background of indeterminate green-brown; the child’s features are mapped but in the vaguest of detail, the face ebbing away without an ear, and the mouth may be passively open against a padded surface rather than suckling. Set apart from the other works, with only a memory from the previous room, the meaning of Child within the company of other works adjusts itself. Are the images we are presented with the subject of an outward or inward gaze or perhaps both? Child suggests a more intimate rationale or perhaps a more private space of looking and imagining.

|

| Orla Whelan: Child, 2007, 30 X 25 cm, oil on canvas |

In contemporary terms, Whelan’s work bears some similarities to that of the painter Paul Nugent. Playing with our observation, both entice us to remain with their canvases in order to determine what we are looking at. Where Nugent tends to work in distorted transparent layers, suggesting that if we just shift our view to one side the true image will emerge, the nebulous haziness of Whelan’s imagery is less perceptual than inherent within the imagery itself, suspended between the real and the imagined. In his recent work [2], Nugent used nineteenth-century photographic negatives as his subject matter, playing with the idea of the original and the work of art, the positive and the negative. This dark side and the subconscious is also evidently a concern for Whelan. Both revisit and remix the history of painting, Nugent reasserting its place within image-making and Whelan playing with imagery in a manner that teases our sense of the real and the imagined.

Monica Flynn is an artist, writer and arts administrator based in Dublin; she is a co-director of The Market Studios, Dublin 7; monica.flynn –at- gmail.com

[1] The German art-historic term meaning ‘back figure’ associated with German Romantic painting; the solitary viewer within the landscape was a figure, which the viewer of the painting could identify with.

[2] Paul Nugent, Vigil, an exhibition of new paintings, Temple Bar Gallery and Studios, 25 September – 27 October, 2007